FACULTY

Faculty Legends: Milton Konvitz and Barbara McClintock

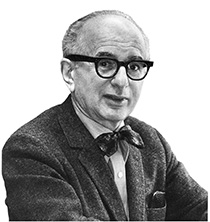

Milton Konvitz was a founding faculty member of the ILR School and taught there from 1946 until his retirement in 1973. Also a Cornell Law School professor, he was an authority on constitutional and labor law, and civil and human rights.

Konvitz was perhaps best known for his American Ideals course, which he taught to more than 8,000 students, never giving the same lecture twice. The course exposed students – including U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg '54 – to the thinkers and philosophers throughout history whose writings had shaped those ideals.

Milton Konvitz. Credit: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. See larger image

At Cornell, Konvitz also was a founder of the Department of Near Eastern Studies and the Program of Jewish Studies. "I felt it was essential for a college interested in the humanities not to leave out Hebrew language and literature," he said. "And the knowledge of Jewish history, which began 4,000 years ago and has contributed to civilization no less than Greek, Roman or English history, is important to today's students – Jewish and non-Jewish."

In addition, for nearly 30 years he directed the Liberian Codification Project, which drew up statutory laws for the Republic of Liberia.

Active as a scholar and writer until his death in 2003 at age 95, he wrote books and articles on American constitutional law that were cited in U.S. Supreme Court opinions. He wrote nine books and edited a dozen volumes, including two on Ralph Waldo Emerson. Konvitz recast one Emersonian idea as follows: "It is in their hearing that students bring life to the words, the thoughts, the teacher."

Konvitz was born in Safed, Palestine (now Israel), in 1908, the son of a rabbi. He immigrated to the United States in 1915. He received a bachelor's degree in 1929 and a law degree in 1930 from New York University and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Cornell in 1933. Before joining Cornell's faculty, he was an assistant general counsel to Thurgood Marshall at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Irwin Jacobs '54, who (with wife Joan Jacobs '54) funds the annual Milton Konvitz Memorial Lecture at ILR, said Konvitz "opened up a new area of thinking" for him. "He really was a wonderful teacher. He gave us much greater insight into the political scene, the legal scene and our heritage," Jacobs said.

Plant geneticist Barbara McClintock '23, M.A. '25, Ph.D. '27, won the 1983 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Her pioneering work in cytogenetics revolutionized the field and had its roots in research she conducted at Cornell decades earlier.

Barbara McClintock. Credit: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. See larger image

Maize captured McClintock's attention soon after she entered Cornell as a freshman in 1919. Studying genetics, she examined plant cell chromosomes under the microscope – a step beyond the then-standard research method of cataloging the results of generations of breeding.

After earning her Cornell degrees in botany, she worked as an assistant in botany and as an instructor until 1931, then studied at the California Institute of Technology and the University of Freiburg. She returned to Cornell as an assistant in plant breeding from 1934 to 1936 before heading to the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island, where she spent the rest of her professional life.

Her work on the cytogenetics of maize in the 1940s and '50s led her to theorize that genes are transposable – that they can move around, on and between chromosomes – a radical theory at the time. But improved technology and techniques in the late 1970s and early '80s allowed scientists to confirm her discovery and led to her Nobel Prize.

In 1965 McClintock was named one of Cornell's first Andrew D. White Professors-at-Large, and during 1965-74 she visited the Ithaca campus regularly to lecture and work with graduate student researchers in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Lee B. Kass, Ph.D. '75, now a visiting professor of plant biology, first met McClintock in 1972 when Kass was a first-year graduate student. Kass says she did not then know of her "reputation for intimidation" and accepted McClintock's invitation to discuss Kass' research in plant chloroplast development.

"She asked me about a paper recently published on the subject," Kass remembers. "When I said I had not read it, she stopped talking and looked at me. 'Come back after you have read the paper,' I recall her saying, 'and we will continue the conversation.'" Kass did and, ultimately, referenced that paper in her doctoral dissertation.

Kass said McClintock "taught us to be open minded, well informed and to think independently. A great legacy for a great mind."