GROWING GLOBAL

From left, Keystone Foundation staffer Sharanya Das, Nilgiris Field Learning Center students Laura Powis '16 and Halammal Rangaswamy, and Janaki-Amma, a resident of Baviyoor village looking out over the hills in Tamil Nadu, southern India. Credit: Samsuda Khem-nguad '17.

Growing global: Cornell continues to expand opportunities for meaningful international experiences

Cornell is and always has been a global university. Cornell faculty, students and alumni are connected through their activities to scholars and leaders across the world.

The Global Cornell initiative, now in its third year, highlights the educational imperative of global education, including global engagement, and helps faculty and program directors across campus build networks to encourage and support development of meaningful international curricula both on campus and abroad.

Through international programs in Cornell's colleges and schools, as well as universitywide units and initiatives, every year more than 2,000 students travel abroad to study, work and serve. It's no coincidence that many of these programs highlight one of Cornell's central strengths: complex, collaborative, multidisciplinary work that is grounded in theory, practice and community engagement.

Here is a look at just a few ongoing programs that build on the university's commitment to internationalization.

Nilgiris Field Learning Center

In spring 2015, seven Cornell students studied and worked at the Nilgiris Field Learning Center in Tamil Nadu in southern India as part of a brand-new semester abroad program, which includes indigenous communities in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. The students, living and working with Cornell faculty, members of local communities and the staff of the partner nongovernmental organization Keystone Foundation, worked on learning modules, fieldwork and research devoted to environmental governance, health and nutrition, and waste production and management.

The Nilgiris Field Learning Center was established in 2013 when then-Vice Provost Fredrik Logevall and Pratim Roy, director of the Keystone Foundation, signed a memorandum of understanding in Ithaca. Roy had developed the concept and framework of the NFLC during his tenure as a Hubert H. Humphrey fellow at Cornell in 2012-13, connecting with faculty and centers across campus.

Cornell and community member students spell out 'N F L C' in the Toda grasslands of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. The Todas are a pastoral community, indigenous to this area. Credit: Keystone Foundation, India. See larger image

Following two years of intense, collaborative planning in both countries, and among administrators and faculty from four colleges at Cornell, the first students traveled to the NFLC for the 15-credit study abroad program.

Neema Kudva, associate professor of city and regional planning, is faculty lead on the project. The other faculty subject matter experts and project partners are Rebecca Stoltzfus (nutritional sciences), Andrew Willford (anthropology) and Steven Wolf (natural resources).

Kudva, who notes that Nilgiris means "blue mountains" in Tamil, says that both the Cornell students and local learners rose to the challenge, traversing a cultural gulf through language study and through their shared work on the research projects.

The program's first seven weeks were spent largely in the classroom, with Cornell students sitting side-by-side with students from the indigenous communities; they learned with and from each other in classes and "Crossing Boundaries" exercises that included situated language learning. The next seven weeks were spent in the field, with Cornellians working on five research projects run out of the NFLC, some developed with community members and Keystone, and others driven by Cornell faculty and student interest. The projects will continue for five years.

NFLC participant Cole Norgaarden '17, an urban and regional studies major in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning, wrote about his NFLC experience in a blog post published at worldsavvy.org. He recalled that he initially wondered how he could do fieldwork on a project "that would span multiple cultures, languages, educations and lived experiences." It was only after living there for a month, he wrote, that he realized he had to change his approach from thinking he was supposed to help improve the "developing" places elsewhere in the world.

"When I first arrived, I saw problems that (to me) had simple solutions," Norgaarden wrote. "But with time I grew to recognize and appreciate the complexity of the issues I was observing, to better understand the culture they were embedded in, and eventually concluded that it was naive of me to think I could (or should) change anything of consequence in the course of one semester.

"Once I was able to shift my mindset about the purpose of my time in India, the work I was doing took on new meaning. Instead of focusing on the results of our research project, I began to pay more attention to the process. By striving to be intentional and inclusive with our communication, we as a team were able to build and maintain meaningful, mutually beneficial relationships across the language and culture divide."

Hope Craig '16 is a biology and society major in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences with a minor in global health and policy analysis and management in the College of Human Ecology. At the NFLC, she worked with her partner, Jeyanthi, on a research project that looked at infant feeding practices among indigenous communities in the region, conducting a focused ethnographic survey that used interviews and observation to collect data on infant feeding, maternal nutrition, and social support systems available for women and children. What made the experience unique for Craig was the strength and resilience of the relationship she built with Jeyanthi during the semester, which she describes as a friendship and trust that "allowed us to work through barriers of cross-cultural collaboration … to better understand one another's perspectives and build off of each other's strengths."

L. Eswari and Meghan Furton '16 use a model they made of the Ambikapuram Valley in the Nilgiris to present their research on the relationship between water and waste in four peri-urban villages near Conoor town. Credit: Neema Kudva. See larger image

"I am grateful for the confidence, patience and empathy that I feel I now carry with me," says Craig, who also built meaningful relationships with her peers and faculty. "The NFLC provided a unique opportunity for me to explore the meaning, value and challenges of cross-cultural collaboration, and engage in meaningful, unique learning."

Craig continued working on the infant feeding research over the summer and now is pursuing a senior honors thesis using the data she collected with Jeyanthi.

Hanna Reichel '17, an urban and regional studies major and a Rawlings Presidential Research Scholar, says the impact of her semester at the NFLC still reveals itself to her in new ways every day. While her previous semesters on campus informed her global consciousness, she says – "making me more aware than ever of the complexity and interconnectedness of contemporary issues, while giving me the background and analytical skills to become a more adept and original critical thinker" – it was the real-world setting of the NFLC that gave her the chance to actualize what she had learned, "with all the virtues and flaws that may only be alluded to in a lecture hall."

Ultimately, the projects worked on by the students and faculty were presented first to community members in the local villages in Tamil. And it was the local community students who made the presentations, with Cornell students as assistants, Kudva says.

"We had elders coming to us saying, 'You don't know how amazing it is to find our kids explaining things to us. It's not an NGO person and it's not an outsider,'" she recalls. "The word they used was 'pride.'"

The Keystone Foundation has been an active presence in the region for 20 years, working with indigenous, tribal residents, Wolf says, in a variety of program areas that correspond to NFLC's program focus on sustainable development and livelihoods.

"The NFLC is the embodiment of community engaged learning," Wolf says. "Cornell students are living with and working with tribal members who speak a different language and come from roadless villages. Together they are living in dormitories, sharing their meals, doing the coursework, doing the research, doing the presentations across a vast cultural gulf. And I think, they are developing reflective capacity on their own knowledge, their own values, as well as learning something about the knowledge, values and prospects of these very different peers."

Laura Powis '16, who studied traditional healing and community wellness in the Nilgiris indigenous tribal communities, says her experience helped her realize her passion for preventive medicine and the use of proper nutrition as a means of combating illness in both developing and developed countries. She has continued pursuing these areas of study since her return from the NFLC, using the relationships she formed with Cornell professors and medical professionals in Ithaca.

Keystone Director Roy says the first year of Cornell students coming to the NFLC has given "being in the field" a "new meaning altogether." Local people have been able to showcase their traditional knowledge and experience, he says, through their approaches and work with the Cornell students.

Roy describes that what surprised him the most is how easily the concept of the NFLC – an empowerment process that builds confidence levels and understanding on both sides – was internalized with the spring cohort of Cornell and local students.

"It was as though they always knew it, and someone just had to place it in this format," he says. "The urge to know about each other and know oneself through an experiential learning and engagement [process was] evident."

Wolf notes that setting up a program this complex certainly had, and has, its difficulties, with organizers in two countries wrangling with budgets, ethical screenings, safety protocols and more.

"The positive thing is that this has been so demanding that the faculty members have really had a chance to know each other, to know [more] about each other's interests, their way of working and what's important to them," Wolf says. "It's been a bonding experience. And it really has been interdisciplinary."

Kudva agrees, saying it has been "an enormous learning curve" for the Cornell faculty members.

"Each of our research programs, the teaching we are doing in the NFLC, represents our disciplinary expertise, and hopefully there are some synergies and the sum is greater than the parts," Wolf says. "And I think we are achieving that in undergraduate education. In research, it's really hard. How do you marry someone who wants to study cultural dislocation and mental illness with someone who wants to study sanitation and water quality? And how we're doing it, is we're sending our students, and our research people, to the same villages. They're doing their research in the same geographic location, and over time perhaps, there will be spillovers."

The students' and faculty members' experiences will also benefit the 550 undergraduates the four faculty partners collectively have in their classes each year, Wolf says. Case studies and curriculum models from the NFLC will be used in the classroom.

Keystone staff will spend some time at Cornell this fall assessing the first semester experience. Roy says he looks forward to the next NFLC cohort arriving at the NFLC in spring 2016, when Cornell students and a new local group of learners will begin their work together.

"From the new cohort we expect an anticipation for a new learning," he says. "An urge to get surprised. Little things – a nuanced, complex understanding and reading of people's lives, aspirations and challenges. … Perceptive leaders who have [both] the local tribal pulse and also the global waves and direction. The single instrument and the orchestra. … The curriculum is changing and will be tweaked to incorporate things that we have learned and given feedback on, [as well as] how to make the integration of teaching and research work on the ground. This is just the beginning."

A SMART Program team worked with the Iketsetse Microenterprise Development Company in Lesotho as part of one of the projects in 2015.

The SMART Program

The Cornell International Institute for Food, Agriculture and Development's Student Multidisciplinary Applied Research Team (SMART) Program pairs teams of students and faculty from diverse disciplines with businesses, community groups and organizations in emerging-market countries to apply classroom knowledge to solve real-life problems.

Since 2002, more than 70 teams (composed of about 250 undergraduate and graduate students in more than 20 degree programs in eight Cornell colleges and schools) have worked on projects in 23 countries.

From left, Bryson Saez, MBA '14; Naomi Makgolo, owner of FoodNet Holdings; Andrew Pike '15; and Stephanie Toro, MPA '15, were part of a 2014 SMART Project team to FoodNet Holdings in Botswana. See larger image

Program coordinator Margaret Lynch '12 says SMART's strengths include the fact that undergraduate students and graduate students work on teams together, and skillsets change each year because the projects, determined by the groups needing assistance, also change each year.

Teams try to draw on Cornell research, Lynch says, and prioritize having a strong faculty "anchor" with experience with the particular partner or client, or who has conducted research in that country.

"We try to tie everything back to a classroom or research," Lynch says.

Past teams have assisted promising new companies to develop strategic business plans; worked with an international NGO to pilot IT training in four African countries; and collaborated with grassroots development professionals to enhance learning outcomes for farmers seeking to increase family food security. Teams work on location with a company or group for at least two weeks and sometimes up to eight weeks.

On their return, students create a case study or a professional report based on their experience; most students draw on those case studies in later coursework.

"I am still in touch with most of the students who have participated in my SMART projects," says Ed Mabaya, associate director of CIIFAD, who has led a dozen projects over the past decade. "For most, this is a truly meaningful engagement where they can transfer skills from the classroom to the real world. It is also a unique opportunity to spend two weeks working with a faculty member who helps them navigate a foreign culture."

"For many students, SMART also opens the door to a career in international development," he adds.

A 2015 SMART Program project team works with the staff of Jabon Kendal Tree Farm and Nursery in Indonesia. See larger image

Lindsey Joseph's SMART Program experience was with CEO Agrifood Limited in Thailand. "It really helped me to expand my mind outside my specific Cornell discipline and learn more about the value of multidisciplinary groups in solving problems," says Joseph, a 2014 graduate. An operations research engineering major, Joseph says her initial interest was in the scientific production of rice, but the program changed her perspective.

"It is a crop that is integral to Thailand's economy, people and culture," she explains. "Its success is equally linked to policy, business and science."

Lin Fu, a doctoral student in government, participated in a SMART project in 2013 and led SMART projects in 2014 and 2015. "I've helped guide Cornell student teams as they research, analyze and write about specific companies and more generally about [small and medium enterprises] development in an emerging-market context," she says. Her involvement with the program has "further solidified [my] research interests that lie at the intersection of business, government and the global economy."

About 10 projects are planned for this year, focused on sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast and East Asia, and South America. Teams will work projects that range from agriculture to management consulting-style projects that include business and marketing strategy, Lynch says.

"We really run the gamut of anything that a client in an emerging market country could possibly need," she says, "and we can draw on the amazing resources here at Cornell to pull a team together to achieve that."

In summer 2015, global health students and faculty, including Douglas Donnelly III '16, Adina Zhang '17 and Francis Ngure, Ph.D., '13, collect baseline household level health and demographic information in Mweka village near Moshi, Tanzania. Credit: Jeremy Swanson.

The Global Health Program

The Global Health Program, run through the Division of Nutritional Sciences, includes course-based and experiential learning opportunities and summer field experience programs in the Dominican Republic, India, Zambia and two in Tanzania (one offered with Weill Cornell Medicine and one offered in conjunction with city and regional planning associate professor Stephan Schmidt).

Rebecca Stoltzfus, M.S. '88, Ph.D. '92, professor of nutritional sciences, directs the program, which offers field experiences in support of an undergraduate minor and a new major, tackles global health problems from a multidisciplinary approach, and engages new researchers and practitioners to address health problems that transcend national boundaries and disproportionately affect the resource-poor.

The program began in 2008 as a collaboration among faculty in four colleges and with a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

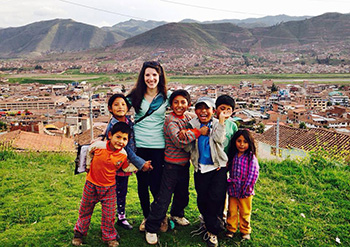

Alma Sana founder Lauren Braun '11 with a group of children in Cusco, Peru, while visiting houses of mothers who took part in her vaccine bracelet program. Credit: Eleonore van Wonterghem. See larger image

"I see that as one of the fundamental strengths of the program – that it's multidisciplinary, and its universitywide framework," Stoltzfus says. "The faculty planners felt strongly that we wanted students' classroom learning to be complemented by real-world experience." The Introduction to Global Health course, a field experience of at least eight weeks and a capstone course upon students' return were requirements from the start.

"We really wanted students … to have to navigate life in the setting in which they were immersed," Stoltzfus explains, "and to do some kind of real work in support of global health," which can be anything from a mentored internship to a health research project.

Between 50 and 65 students complete the minor every year.

Experiential learning means more than students learning in the field, Stoltzfus says; it means continuing learning and processing the experience on their return. Everything from the preparation course to writing assignments in the field to group discussions in the capstone courses (or conversations late at night in Collegetown, she adds) deepen the experience.

Hijab Khan '16 completed the program's Tanzania field experience in 2014, spending two months in East Africa shadowing at a hospital.

Khan, who says she found her niche at Cornell when she discovered the field of global health, says the experience allowed her to nurture her interests in human health and human rights; since that summer, she says, "my passion for those subjects has only grown, and my career goals have shifted from clinical medicine to global health.

The first baby enrolled in the Alma Sana bracelet program in Ecuador shows off his ankle bracelet. Credit: Alex Bozzette. See larger image

"I can no longer consider health without considering its context in the world, and I want to understand how it interacts with other fields like policy, culture and environment before trying to improve it."

The Global Health Program's student advisory board offers leadership roles, additional programming and special projects. Alumni of the program also have input and access through the Global Health and Development Alumni Mentorship Program, where students are paired with an alumni mentor.

Khan has since become more involved in the program as a teaching assistant and student advisory board member "so that I might help other students make that same discovery," she says.

Following her global health field experience in summer 2009 at a rural health clinic in Peru, Lauren Braun '11 came up with the idea for a simple, inexpensive immunization-tracking reminder bracelet for babies. She formed the nonprofit Alma Sana (Spanish for "healthy soul") to manufacture and distribute the bracelets, which bypass language barriers and illiteracy by using symbols to show mothers (and public health workers) the vaccinations children need and when they are due. The bracelet is worn by a child from birth to age 4, with the goal that more children will live to age 5.

In 2012 Braun received a $100,000 Gates Foundation Grand Challenges in Global Health Initiative grant to field test the bracelet. Initial field tests in Peru and Ecuador were completed earlier this year (91 percent of moms said the bracelets helped them, Braun says); now Alma Sana is actively fundraising to conduct additional trials and impact evaluations and to scale their work to multiple countries to help save thousands of children's lives.

Melissa Miles '16, with her homestay family, learns how to grind 'mealie-meal' (coarse flour from maize) which then gets boiled in a large pot on a wooden fire outside and made into a traditional drink for the 'Matebeto,' a traditional Zambian wedding ceremony. See larger image

Braun, who came to Cornell interested in health care and planned to become a doctor, discovered the field of public health in the College of Human Ecology and had an epiphany, she says. "I had the feeling, this is what I'm supposed to do with my life … I knew I wanted to work in health care, but work in public health allowed me to help a lot more people in a day, and I could work on a much bigger scale, whether it was in policy or data analysis or something like I'm doing now. I also really wanted to get out and start working."

Listening to the people you're working with was her biggest takeaway from the program, she says.

"That mindset allowed me to be in an open position to receive and value their comments and feedback, and design a product around their needs," she explains, "listening to the problem and immersing myself in it."

These are only a handful of the complex, multidisciplinary Cornell programs that have been developed by faculty across campus to offer meaningful international experiences to undergraduate students. Examples of other major programs include the Tata-Cornell Agriculture and Nutrition Initiative, a research program focused on solving problems of poverty, malunutrition and rural development in India; international agriculture and rural development programs that address interdisciplinary issues associated with food systems and rural development in emerging nations; the Cornell-Cuba Research Program, which offers students the opportunity to study and conduct research (in bioacoustics, neuroethology or protein studies) at the University of Havana; and the Cornell in Seville Program, in consortium with the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan, in which students experience life in a Spanish household while they study with local students at the University of Seville.

For more information and resources about international opportunities for students and faculty throughout Cornell's colleges and schools, visit http://global.cornell.edu and www.cuabroad.cornell.edu.