CORNELL PEOPLE

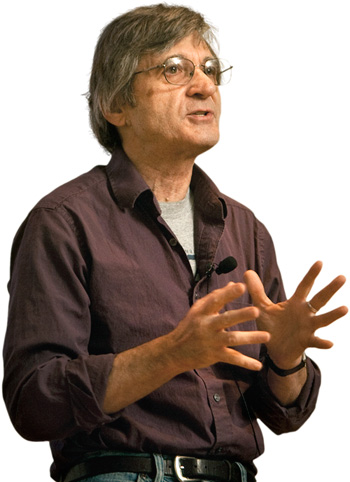

David Levitsky See larger image

David Levitsky -- part teacher, part showman

Central to David Levitsky's teaching philosophy, honed over 40 years of instructing Cornell students, is to make his lessons unpredictable.

To wit, Levitsky, professor of nutrition and of psychology, has donned an apron to show students how to stir-fry tofu, asked his class to evaluate incredible weight loss ad claims as he peddled them like a TV pitchman, and stripped down to his gym shorts and T-shirt, mid-lesson, and run around Kennedy Hall as a way to explain exercise and body chemistry.

"I still get e-mails from students in medical school and out in their careers years later to remind me about that lesson," Levitsky said of his impromptu calisthenics.

For his inimitable teaching style, Levitsky earned a 2009 Excellence in College and University Teaching Award from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He received the award, given for "effective and innovative pedagogy evidenced by successive years of sustained, meritorious and exceptional teaching," at the annual meeting of the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities in Washington, D.C., last fall.

Since arriving at Cornell from Rutgers University as a postdoctoral fellow in 1968, Levitsky has taught thousands of students about the principles of food intake, weight loss and gain, and nutrition. His popular introductory course, "Nutrition, Health and Society," has swelled to 600 from 40 students in the past two decades, and every other year about 200 students take the more advanced "Obesity and Control of Food Intake."

Students rave about Levitsky's offbeat lectures, but his teaching philosophy goes beyond his "make it memorable" credo. His other maxims are: students and professor are on the same side; students must feel course grading is fair; professors must keep pace with technology; and the professor must be excited about the topic for students to be excited about the topic.

On the first two points, Levitsky created "the 70s club," a voluntary group for students who score 70 or below on the first class exam. With a teaching assistant's guidance, the club scrutinizes test questions and course concepts in special sessions that amount to a how-to on studying. On average, 70s club students score 2.5 grades better on the their next exam, according to data tracked by Levitsky, whereas most who skip the extra lessons score poorly again. A few 70s club members have even gone on to become teaching assistants for the course.

"Too often, the professor-student relationship is viewed as adversarial: The students are out to find shortcuts, and I'm out to trick them," said Levitsky, a Stephen H. Weiss presidential fellow. "I want everyone in my course to get an 'A' as long as they are willing to work hard. If they're failing, so am I."

Even after four decades as a professor, Levitsky delights in the challenge of captivating a roomful of students with multiple potential distractions at their fingertips and seated around them.

"Giving a lecture is like storytelling," he said. "I have to gain their interest right away, hold their attention as I develop an idea, and then leave them with a message they'll remember."

After 40 years of teaching at Cornell, David Levitsky gets raves from students about his offbeat lectures, but his teaching philosophy goes beyond his make it memorable credo.