COVER STORY SIDEBAR

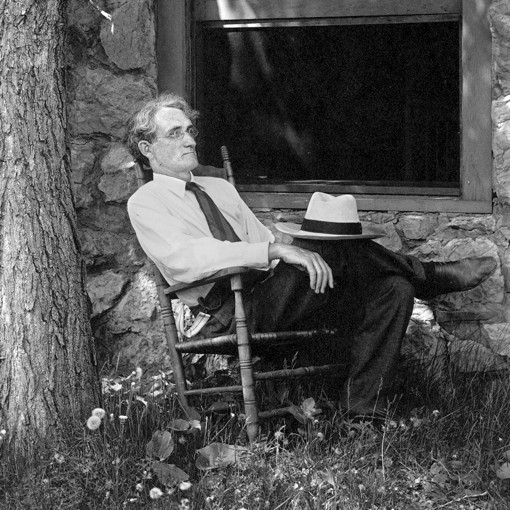

Faculty legends: Liberty Hyde Bailey

Liberty Hyde Bailey. Photo: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.

"He will undoubtedly have a great influence on the horticultural interests of the state," reported The New York Times in 1888 about Cornell's hiring of Liberty Hyde Bailey for the newly established chair of practical and experimental horticulture.

History has proven this prediction to be too modest.

Born on a small farm in Michigan in 1858, Bailey grew his boyhood passion for nature into far-reaching teaching, scholarship and leadership. Garnering the respect and support of farmers, uniting disciplines and lobbying for state support, he transformed Cornell's Department of Agriculture (1874) into the College of Agriculture (1888) and later the New York State College of Agriculture (1904), of which he became the first dean. Today's College of Agriculture and Life Sciences would not exist without Bailey's vision.

As dean, Bailey developed many areas of study, including the Department of Home Economics, later to become the College of Human Ecology. He also staunchly advocated for women in education, appointing the university's first female professors, Anna Botsford Comstock, Martha Van Rensselaer and Flora Rose – legendary leaders who would also help shape Cornell.

Bailey broke down boundaries among disciplines and between the university and outside communities. Among his 65 books, he co-wrote "The Amateur's Practical Garden Book" with C.E. Hunn, a gardener, to engage nonacademics. From learned societies to grange meetings, he called for demolishing "the barrier between theory and practice." In addition, he pioneered extension programs to "meet the needs of the people on their own farms and in the localities," he wrote, while his influential teaching and writing for the nature-study movement brought the wonders of nature to rural schoolchildren across the nation. In 1908, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Bailey to chair the Commission on Country Life, where Bailey's recommendations eventually led to a nationalized extension service and the creation of the American Country Life Association in 1919.

Retiring in 1913, Bailey continued his scholarship – editing and writing textbooks, poems and philosophical musings, as well as traveling to different countries to collect and document specimens. Today, more than a half century after his death in 1954, his expansive hortorium collection and voluminous writings stand as testaments to a life dedicated to what he described as "the spiritualization of agriculture."

"We know that we cannot reap the harvest, but we hope that we may so well prepare the land and so diligently sow the seed that our successors may gather the ripened grain," Bailey once said of Cornell's land-grant mission. The same holds true for his life's work, which continues to enlighten and inspire scholars and enthusiasts today.

– Jose Perez Beduya