DEANS Q&A

Deans

Q&A with Cornell's deans: On entrepreneurship, cities, newcomers to Ithaca and brain power

In this, Ezra's second installment in an ongoing series of conversations with Cornell's academic deans, we again hear the real voices – sometimes candid, sometimes very specific, always revealing – of leaders who are deeply involved with the everyday work and negotiation involved in steering a large university.

How will the Cornell Tech campus in New York City change Cornell University? What's the most important budget item these days? Are expensive buildings worth the cost? How is graduate school changing? And what do these leaders expect in Cornell's future? These are the people with a front-row view on the action, and here's what they see.

Kent Kleinman

Dean Kent Kleinman with, from left, Mauricio Vieto, B.Arch. '13, Joshua Rolon '13, and Julie Casablanca, MRP '14, on the Ho Family Bridge in Milstein Hall.

What are you most proud of in your first term as dean?

I was thinking I'd say the obvious – the facilities – but that's actually not the case. It's really the people. I came in 2008, which was a particularly tough time for higher education due to the economic downturn. When I reflect back, what I'm most proud of is that we were able to continue to attract an exceptional student body and recruit a steady stream of new faculty. I'm an architect, and one might think that it would be easy for me to say buildings matter over everything else, but in the end, our past and future greatness rests on the quality of the faculty. If we have fantastic facilities and don't have fantastic faculty, we will not be a top-tier program.

What's the biggest obstacle to success for your college right now?

It's funds – funds to continue to bring in the best faculty and continue to allow the best students to come to Cornell. At the undergraduate level, there's a profound and noble principle at Cornell regarding financial aid, and anything we can do to continue our need-blind admissions and need-based aid programs is essential. But equally important is support for graduate students. Our disciplines – particularly architecture but also art and planning – are often misunderstood as professional disciplines only, but they really have many components of a liberal arts education and, quite frankly, compensation after graduation commensurate with other graduate research programs.

Kleinman with architect Richard Meier '56, B.Arch. '57, in 2012 during Meier's visit to campus. See larger image

Our graduates are frequently cultural critics. They are engaged in the public realm, they're advocates for social equity and often serve as public intellectuals. Our curricula have many courses that are not merely professional in nature. Our graduate professional students need financial support to be able to pursue diverse career paths after they graduate, because they're not going to Wall Street. They're going to work for communities, they're going to work for international government agencies. They're becoming artists, they're working for small architecture firms doing speculative competitions. They need to be able to afford the education we provide without the promise of high salaries after they graduate.

Has Milstein Hall, now approaching two years old, fulfilled all that it promised to be?

What I would say to Ezra readers is they have to come back to campus and experience Milstein Hall, because anything I say is inadequate – it's spatial and material and it has to be experienced firsthand.

From my perspective, and I think I speak for most of the faculty and staff and probably all of the students as well, it's fantastic. It's brought us together in ways that we were not able to imagine before. It's not just a building, it's not just an addition – it's a uniting fabric. In terms of the future way that the disciplines of architecture, art and planning will need to work collaboratively, having a building that unites, especially a structure that encourages ad hoc interactions, is priceless. I say priceless deliberately because it wasn't the cheapest building! But it has been transformative for us.

Do you think planning and art at Cornell have the opportunity to achieve the status and visibility that AAP's architecture programs have?

Yes – because the world is urbanizing. More people are living in cities than ever before, cities are bigger than they ever were, and they're more complex than previously. The importance of the urban is undeniable. It affects every walk of life; it's changing cultural patterns, changing living habits, changing aesthetic practices, changing our sense of identity. Planning is the disciplinary glue for conceptualizing the city. We have a distinguished planning faculty, very strong students, and the department already enjoys international visibility. It's a very highly ranked [No. 2] graduate program, and I predict it's going to become even more important as an area of research and study as the city dominates our attention. How does one manage and provide for a high quality of life in cities of over 20 million people? That is an almost intractable question but a very real and urgent issue. Planning departments will inevitably be at the center of that conversation.

On the art side, this is somewhat bold, but I think the next big jewel in the Cornell crown has to be the arts. Across the university, we have many individual students and artists doing scholarship in the arts – and by this I mean advancing our understanding of the human condition via material, visual, formal creative practices. People in fiber science, in landscape architecture, of course in the fine arts at AAP: somehow their individual activity hasn't coalesced into a strong identity for Cornell arts. I think it can and should. The model of an artist going to an atelier [studio] and waiting for inspiration and making a mark on a canvas – that is a completely antiquated model, if it ever really existed.

Artists today are publicly engaged, theoretically reflective, intellectually informed, creatively innovative. Art making is a form of inquiry just like other academic modes of producing new knowledge and insight. What better place to educate talent like that than a top research university?

You mentioned the campus being like a work of art. Do you have a favorite spot on campus, inside or out?

Many people focus on the buildings, and there are certainly beautiful physical structures at Cornell, both historical and contemporary works of architecture. But really what's quite extraordinary are the spaces where there are no structures – the gaps between buildings, the quads, the vistas. So I would say that one of my favorite aspects of the campus is how intelligently the negative space, or open space, has been configured. It has a palpable presence, almost as if it were made of material. The balance between the physical structures and the residual space is a very deliberate one. I think that's what makes the campus such a delight.

The DeanKent Kleinman, the Gale and Ira Drukier Dean of the College of Architecture, Art and Planning At Cornell since 2008 Dean since September 2008 Area of expertise: 20th-century modernism College of Architecture, Art and PlanningPopulation: 56 professors, 493 undergraduates, 278 graduate students Major areas of future growth: New York City program, B.F.A. dual-degree program, urban design concentration Endowment: $62.1 million (as of March 2013) Cornell Now campaign goal/amount raised so far: $30 million / $13.6 million (as of April 2013) |

Lance Collins

Dean Lance Collins chats with engineering students Julie Wang (electrical and computer engineering), left, and Nicholas Chmelev (civil and environmental engineering), both Class of 2014.

What's one thing that most outsiders don't understand about the College of Engineering?

I think the stereotype of the engineer is that we're a bunch of nerdy people in the background, keeping the lights on and things working. That's just false. I think the engineer is the creator, the creative force behind innovation, behind the way that our world keeps advancing. That is the new reality. It's an evolution, but a pretty substantial one. Over the course of my career, I have seen engineers increasingly as the leaders, and not just the group providing the mix of expertise required to keep things going.

There were some early critics of Cornell's bid to win the New York City tech campus, a contest you played a large part in winning for the university. Some people are still worried about its potential effect on the Ithaca campus.

Because of the heightened awareness of the Cornell Tech campus, we have actually seen a much higher level of excitement for the College of Engineering as well. More alumni are giving, and more students are applying to the Ithaca campus. We've set records in terms of philanthropy over the last couple of years.

I interact with a tremendous number of alumni as well as with faculty and students, and there is an incredible level of excitement among the alumni, about the tech campus and what this means for Cornell as a whole.

Will Cornell Tech skew things toward engineering for money, for business, rather than for the greater good?

The greater good will always be served by taking technology out of the laboratory and putting it into a product that can be sold. Even commercial activities can be driven by all sorts of interests.

Collins with Dan Huttenlocher, then dean of the Faculty of Computing and Information Science (now dean of Cornell NYC Tech), at the inaugural Startup Career Fair held in Duffield Hall Atrium in February 2012. See larger image

For example, one of my colleagues, professor Brian Kirby, has developed a microfluidic device that allows you to take the blood of someone with prostate cancer and lets you separate the cancer cells from all the other cells, which potentially allows the urologist to determine and treat the precise type of cancer that person has without doing an invasive procedure. The technology works reliably in the laboratory, but if you don't actually commercialize it into an easy-to-use system, then no physician will ever use it and no patient will ever benefit from it. Setting something like that up in the lab is just enormously difficult, and the average urologist is not likely to go through that trouble. So the technology benefits no one unless it is commercialized.

What have you learned from the other deans, with whom you meet weekly?

The meetings have been a pleasant surprise: We collectively work as a team for the whole university. I thought, when I first became dean, that that was the responsibility of the president and the provost, without realizing that it was really the leadership team, consisting of the president, provost, the deans and the vice presidents who collectively work together to figure out where the university is going. And we've gone through a pretty difficult time, arguably the worst economic downturn in close to 100 years. So that required incredible levels of stewardship and incredible levels of selflessness. You can't simply be the dean of engineering under those conditions. You really have to be a dean who is servicing the whole university. So I learned that we, as a group, work for the benefit of the whole institution, and sometimes that requires that our vision extend beyond the boundaries of our respective colleges.

What are the major areas of growth and change for the College of Engineering?

We're investing in growing our biomedical engineering department. This department was created in 2005 and has rocketed upward. It is currently ranked among the top 15 to 20 departments in the country, which in that short amount of time is a meteoric rise. It is a group of very young, very talented faculty who, along with some outstanding senior colleagues (including Mike Schuler, the founding chair of the department), have been guiding its growth in spectacular fashion. While biomedical engineering is the core, there are a significant number of faculty members in the other engineering departments contributing to the overall bioengineering effort. This is one of the significant investment areas for the college.

A second major investment area is energy. Under the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future, there are the three "E's": energy, environment and economic development, and the energy component to a large extent, but not exclusively, lies in the College of Engineering. We have the Energy Institute, which is now being run by Jeff Tester, the David Croll Professor of Sustainable Energy Systems. We serve as the focal point of energy research across the campus, and we plan to expand those activities. We're very interested in renewable energy such as wind energy, wave energy, solar energy, as well as more traditional, fossil-fuel-based energy sources. We're also interested in the distribution of energy. It's one thing to create it; it's a completely different thing to get it to where you need it, when you need it.

Tell a bit about yourself when you leave the office, at home, and your other interests?

My family is most important to me. My wife, Sousan, a nurse by training, is a stay-at-home mom to our 12-year-old daughter, who has a passion for dance and is also a terrific flute player. I'm happy to see that she does have a math aptitude that maybe takes a little after her dad. So we're trying to make sure she keeps all those options open, but I'm not the kind of dad who says, "You've got to be an engineer to make me happy."

I was an athlete when I was in high school on Long Island. I ran track and played soccer. Now, in my crazy life as a dean, my sporting activities have evolved into spinning classes several times a week.

The DeanLance R. Collins, the Joseph Silbert Dean of Engineering At Cornell since 2002 Dean since July 2010 Area of Expertise: Fluid mechanics, with a special focus on turbulence in clouds The College of EngineeringPopulation: 236 full-time faculty members, 2,903 undergraduates, 1,705 graduate students Major areas of future growth: bioengineering; energy; advanced materials and complex systems; network science and computation. Endowment: $523 million (as of June 2012) Cornell Now campaign goal and amount raised so far: $185 million/$95.9 million (as of April 2013) |

Stewart Schwab

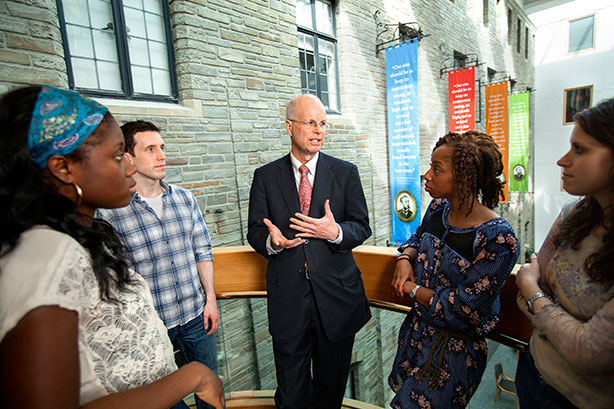

Dean Stewart Schwab, center, chats with, from left, Malissa Osei J.D. '14, Conor McCormick J.D. '14, Danielle Jones J.D. '14 and Jocelyn Krieger J.D. '13 in the Law School's Berger Atrium.

What is something people don't realize about Cornell Law School?

How much we engage with the rest of the university. We recognize that for the students who are graduating in 2013, as quickly as five or 10 years out, many current statutes will be old and new statutes will be in, so our curriculum is not memorizing – it's understanding the forces and the policies. For that reason, we try to interact with a lot of the rest of the university: law and economics, law and philosophy, law and literature, law and anthropology. We're also engaged in efforts with Cornell Tech and the Johnson school regarding entrepreneurship, venture capital and intellectual property.

Isn't law school known for being a professional school that is hard, but doesn't necessarily prepare you, right away, to do the job?

Being a lawyer is a lifelong learning experience. There are a lot of directions and careers that lawyers can take, so certainly experience helps. There is an expectation nowadays that law graduates need to hit the ground running. And while certainly I agree with that no one wants to hit the ground crawling, I think it can be overstated. It's related to the issue of the law moving; 20 to 30 years from now the issues and statutes will be quite different. We're making sure that our students are profession-ready, recognizing that it's a lifelong career.

Schwab greets Her Royal Highness Princess Bajrakitiyabha Mahidol of Thailand, LL.M. '02, J.S.D. '05, during her 2012 visit. See larger image

I often say that law is the most intellectual of all professions, and my friends in architecture or medicine can make their own claims, but I do think that those who are particularly good at law have a wide range of interests and don't think their learning stops when they leave here.

Tell us about yourself when you're not doing this job.

Well, my wife and I are both from North Carolina. We grew up together and were high school sweethearts. She's also a lawyer who works as Cornell associate university counsel. She was the city attorney of Ithaca before that and has been in the district attorney's office and in private practice. And the other distinctive thing about us is that we have eight kids. Five of the first six have gone to Cornell, including our high school senior who's going next year. The other graduated from Ithaca College. So we have sort of a large family.

How did you manage to juggle all that with your careers?

Well, Norma is very organized. And Ithaca is very helpful for combining family life and academic or professional careers. It's a lot easier to do here than in a big city.

How did you get interested in the law?

After college I went to the University of Michigan to get a Ph.D. in economics. … I wanted to think about justice and fairness and how they interact with economics, and so pursued a law and economics degree.

Right after law school, I went to clerk for a federal judge and then two years out I clerked for Justice Sandra Day O'Connor on the [U.S.] Supreme Court.

How does legal scholarship affect policy and people in a real way?

Some of the most interesting scholarship in all of the social sciences is being done here in the Law School. We are using a variety of perspectives from other disciplines, with one sort of normal pressure: it's got to have some sort of policy relevance. That doesn't have to mean a judge or lawyer can use it directly in a case, or that it's specifically talking about a piece of legislation in Albany or Washington, but [it must have] some sort of policy relevance which keeps us from being too esoteric.

You know, there are a lot of think tanks out there and a lot of policy think tanks with a law-policy focus similar to what law schools do, but I think the best scholarship occurs here in the law schools. Why? Because over the course of the semester, the freshness, the thought, the criticism of the students, and having to explain the issues to students, all this makes teaching and scholarship reinforce each other.

What are you most proud of?

In my time as dean, we've expanded our business law curriculum with new deals and transactional law classes and created new clinic opportunities in labor law, LGBT rights and juvenile justice.

Faculty members have created new programs and institutes at the forefront of legal thought. The Clarke Business Law Institute, Cornell e-Rulemaking Initiative, Avon Global Center for Women and Justice, and Clarke Initiative for Law and Development in the Middle East and North Africa have all launched in the last decade, and the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies has blossomed.

We have expanded our study abroad opportunities and established exchange partnerships with some two dozen universities around the world. Recent countries where we've expanded our reach include Chile, China, India, Norway and South Africa.

After many years of plannning, we are well under way on Phase 1 of a multi-phased project to renovate and expand the physical plant of the Law School. This addition is the first in 25 years and the new teaching wing will be ready for students in the spring semester next year.

I'm also happy to report that last year was our most successful fundraising year in the history of the Law School.

But, overall, I'm really most proud of the collegial and supportive atmosphere we have nurtured here. We take pride in each other's work, learn from each other and from our students, and push each other. I am grateful to work with brilliant and highly effective colleagues who take the work seriously but themselves less so.

The DeanStewart J. Schwab, the Allan R. Tessler Dean and Professor of Law At Cornell since 1983 Dean since 2004 Area of Expertise: employment law, economic analysis of law The Law SchoolPopulation: 50 full-time faculty members, 586 J.D. students (three-year program), 84 international L.L.M. students (one-year program), 16 J.S.D. students (3-5 year program) Areas of future growth: intellectual property, business law, empirical studies, and international and comparative law. Endowment: $150 million (as of March 2013) Cornell Now campaign goal: $35 million; raised so far: $36.9 million (as of May 2013) |

Barbara Knuth

Barbara A. Knuth, vice provost and dean of the Graduate School, hoods Deondra Rose, Ph.D. '12, at the Ph.D. hooding ceremony during Commencement Weekend 2012.

What are you most proud of in your first term as dean?

I'm most proud of the effort we've undertaken to improve the Graduate School's capacity to support graduate and professional students. We've redesigned how we deliver services to [them]. We created the Office of Inclusion and Professional Development, which is providing a broad, very robust and comprehensive set of programming activities to support graduate students' academic success while they're here, and to foster a set of transferrable skills that will help them when they begin their careers. We've revamped our Office of Graduate Student Life to better support the whole person with a stronger focus on mental health and well-being, personal financial management, and family and partner support.

We also joined a National Science Foundation initiative, the Center for the Integration of Research Teaching and Learning, a network of 22 universities across the United States that focuses on future faculty development in the STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] disciplines – ultimately with the goal of enhancing undergraduate education in the STEM disciplines by improving how future faculty integrate their research and teaching into one cohesive approach using evidence-based teaching and assessment.

What is one thing most people outside the Graduate School don't know or realize about it?

The Graduate School's size and scope. I don't think most people recognize that we actually oversee nearly every degree program on the Ithaca campus and the Cornell Tech campus that's not the first degree offered by the school. For example, the MBA is the first degree offered by Johnson, but any Ph.D. students who work with Johnson faculty are actually Graduate School students. The Graduate School confers 18 different research and professional degrees – there is no other unit that confers that many – across nearly 100 graduate fields.

Knuth with students at the 2012 Tata Scholars reception. See larger image

What's the biggest obstacle to success for graduate education right now?

Funding; that's probably not a surprise. Certainly what's happening with the federal budget is worrisome in the sense that a significant proportion of our graduate students are supported on research assistantships from external grants, particularly Ph.D. students in the STEM disciplines.

An aspirational goal for the Graduate School is to have funding available to support all of our Ph.D. students with a first-year fellowship. We have about 500 first-year Ph.D. students, and enough first-year fellowships for about half that number, so it will take considerable resources to meet our goal.

What was one of your expectations about the job that proved untrue?

I didn't expect to have the opportunity for as much interaction with the graduate faculty as I actually have. The faculty who are directors of graduate studies throughout these 100 fields and the faculty who are elected to our general committee (the governance body of the Graduate School) have been quite collaborative, very eager to engage in policy and program discussions with the Graduate School to support their graduate students.

For example, we asked each of the graduate fields within the last year to undertake a fairly comprehensive project to explicitly identify a set of learning outcomes for their students in each degree program and to develop assessment plans to help evaluate how students are achieving those learning outcomes. Most fields took that on in an enthusiastic and committed way, and have already identified improvements in their programs as a result of this information.

How do you balance your roles as a vice provost, dean and researcher?

With a lot of support from my husband, my daughters and my executive assistant. On the research side, the support of my research team, which includes two doctoral students and several research staff, has been invaluable.

One of the reasons I've been able to keep my research program going is due to a phenomenal group of faculty in natural resources who have been working together for a number of years. The group is called the Human Dimensions Research Unit, and we focus collectively on understanding human behaviors and attitudes toward the environment. We collaborate; we pool our resources. This partnership has made it possible to continue my research, continue mentoring students, and work with interesting research colleagues while I have these very busy administrative jobs.

How would you describe the importance of the developing Cornell Tech campus to the future of graduate education?

The Cornell Tech campus raises the visibility of graduate education at Cornell, particularly because a good portion of graduate education – not just at the tech campus but at our campus as well – is really focused on addressing societal issues. One of the hallmarks of Cornell Tech is the partnership between industry and academics.

That partnership between academic and nonacademic – in their case industry – is very similar to what we do across much of graduate education at the Graduate School, which is to partner academic with nonacademic in diverse ways, with students focusing their studies by working with agricultural communities, rural developing communities and urban communities across the world, bringing our graduate student research to bear on the problems that these different places and different groups of people are experiencing.

The DeanBarbara A. Knuth, vice provost and dean of the Graduate School, and professor of natural resource policy and management; as vice provost, she oversees undergraduate admissions, financial aid and student employment At Cornell since 1986 Vice provost since April 2010; dean since July 2010 Area of expertise: Human dimensions of natural resource policy and management The Cornell Graduate SchoolPopulation: 1,800 faculty affiliated with nearly 100 graduate fields; 5,200 graduate and professional students Major areas of future emphasis: increased internationalization of the graduate and professional student body; enhancing infrastructure for graduate education in support of Cornell's strategic priorities Endowment: $76.9 million (as of February 2013) Cornell now campaign goals: $100 million for graduate fellowships and professional school scholarships and $182 million for undergraduate financial aid are universitywide goals |