WWII-era spy Stephanie Czech Rader '37 dies at age 100

Stephanie Czech Rader '37 celebrated the Cornell sesquicentennial at the Washington, D.C., event in November 2014. Photo: Diane Bondareff.

Stephanie Czech Rader '37, a chemistry graduate who became a U.S. spy in Europe at the end of World War II, died Jan. 21 at the age of 100 at her home in Alexandria, Virginia.

Among the university's oldest alumni, Rader had participated in Cornell's recent sesquicentennial celebrations -- she was honored at a Washington, D.C., event in November 2014, where she was welcomed on stage at the Warner Theatre with resounding applause in front of a crowd of more than 800 fellow Cornellians.

After earning her Cornell degree, Rader worked as a librarian and researcher at the Texas Oil Co. in New York City before joining the first 80 trainees for the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) at the outbreak of World War II. WAAC became the Women's Army Corps, and she was one of the first 440 women selected to participate in a six-week officer candidate training class at Fort Des Moines, Iowa. As Rader trained enlisted classes, she quickly rose to the rank of captain. In the waning months of the war, she also became a spy for the U.S. government.

Stephanie Czech Rader was among the first 80 trainees for the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps and one of the first 440 women selected to participate in a six-week officer candidate training class at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, during World War II. She quickly rose to the rank of captain. Photo: provided.

Rader was recruited by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency. Raised in Poughkeepsie, New York, by parents who were emigrants from Poland, she had always been immersed in Polish culture and language, and so the OSS assigned her to Warsaw in late 1945.

Working undercover as a U.S. embassy clerk who was attempting, in her spare time, to reconnect with distant relatives in different parts of Poland, Rader traveled far and wide across the Russian-occupied country while gathering intelligence on Soviet troop movements and other population data. She was shocked by the bombed-out devastation around her, and she continued to be vigilant, always "collecting all kinds of information."

Rader's covert role placed her in precarious situations, which she handled with uncommon poise. "[The OSS] gave me a gun, but I never carried a gun. I thought, 'What the heck was I going to do with a dumb gun?'" Rader said in an OSS Society interview.

In 1946, Rader returned to the United States and married Brig. Gen. William Rader. She retired from the Army with the rank of major but continued her involvement with the military as her husband served in Air Force command positions around the country.

Rader received the Army Commendation Ribbon (now known as the Army Commendation Medal) in 1947, but it took decades for Rader to receive any further recognition for the true extent of her assignments and activities. Her personnel file was only declassified in 2008. In 2012, she was honored as the inaugural recipient of the Virginia Hall Award (named after the famed Allied spy) by the OSS Society, and a separate effort was underway at the time of her death by friends of Rader and the OSS Society to award her the Legion of Merit for "exceptionally meritorious conduct in performing outstanding services." Rader had been nominated by her superior officers for this honor in 1946, but the request was turned down for unknown reasons.

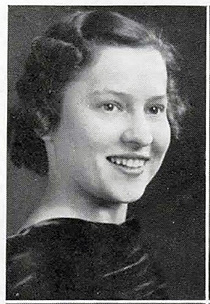

Stephanie Czech's photo in the 1937 Cornellian.

In a Jan. 21 article in The Washington Post, OSS Society President Charles Pinck said Rader "was never properly recognized for her heroism" and that he hoped the Army will award her the Legion of Merit posthumously.

In recent years, Rader had joined the Cayuga Society, a group of individuals who have entrusted their bequests to the university. Rader said she made her bequest, to benefit chemistry faculty and students in the College of Arts and Sciences, out of her gratitude for the confidence Cornell instilled in her.

In 2015, shortly before she turned a century old on May 15, Rader looked back at another act of generosity that enabled her to make a difference for Cornell and for her country. "I had a high school teacher who graduated from Cornell. I was a good student in high school, and she took an interest in me," she recounted.

Rader's parents barely spoke English, and they were unfamiliar with the American collegiate system; however, Rader's teacher served as her mentor and later submitted a Cornell application on her behalf without her knowledge.

Rader received a full scholarship, which she supplemented by waiting tables, and she became the first member in her family to graduate from college. After Cornell, what followed was indeed a remarkable adventure -- the kind one hears about in spy movies.

Stephanie Czech Rader '37 attended the Washington, D.C., Cornell sesquicentennial celebration event with Michael Golden '62 in November 2014. Photo: Diane Bondareff.

Michael Golden '62, a fellow Alexandria resident, and his wife Margie befriended Rader in recent years and attended the sesquicentennial event in Washington, D.C., with her.

"Stephanie was a strong, intelligent, motivated, decent person, with strong opinions masking her wonderful sense of humor, who believed that her Cornell experience created opportunities that she otherwise wouldn't have had," Golden said. "She paid that back full bore through her dedicated military service in WWII and afterward. And she felt that way from her first day on the Hill to her passing 82 years later. And she wanted other young people to be afforded that same opportunity. She was thrilled to have been honored at the 150th gathering at the Warner Theater, and to give a 'high five' to the Big Red Bear."