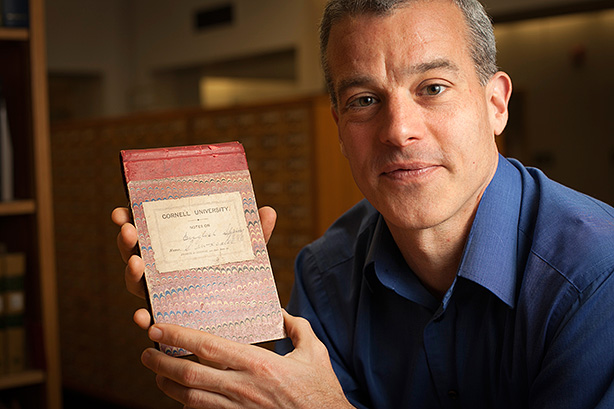

Dan McKee, the Japan curator for Cornell University Library, with the Cornell notebook he found at a Tokyo flea market. Photo: Jason Koski/University Photography.

Japanese alum's 1886 notebook returns to Ithaca

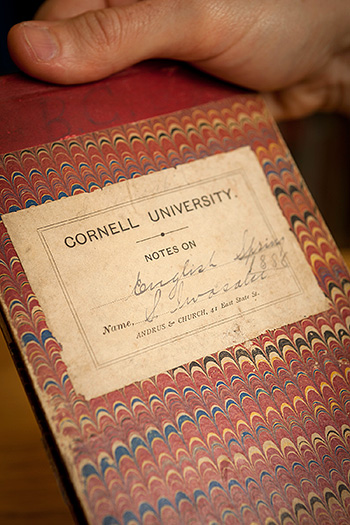

The notebook, dated spring 1886, had belonged to a Japanese student enrolled at Cornell, Seikichi Iwasaki, and had been used for an English class. Photo: Jason Koski/University Photography.

When Dan McKee decided to go for a run on a brisk February morning in Tokyo, he had no idea he was about to uncover a little piece of Cornell, 6,000 miles from home.

McKee is the Japan curator for Cornell University Library, and he takes annual acquisitions trips to Japan to find rare books or manuscripts that are difficult to find or prohibitively expensive to get in the United States.

In Ithaca, McKee had been training for the Boston Marathon. On his third day in Tokyo, jet-lagged and unable to sleep, he decided to go for a 20-mile early morning training run.

On his way back, he stopped by an antiques fair he had passed earlier to look for "woodblock printed books, rare manuscripts, anything we might consider valuable for our collection," he says.

He didn't find anything promising until, at the very edge of the fair, he saw a dealer selling scraps of paper and old textbooks. As McKee flipped through a box, a small hardcover notebook caught his eye.

"It said 'CORNELL UNIVERSITY' on the cover in bold letters. I opened it up, and inside, there's an old stationer's label inside that says 'State Street,'" he remembers. "So now I'm having this déjà vu moment … It really struck me; these kinds of karmic connections happen all the time in medieval Japanese tales."

At first, McKee thought the coincidence was just amusing -- until he saw the date on the notebook.

Seikichi Iwasaki

"It was 'spring 1886,' and that's when I realized it was actually important. The 1800s meant this was a truly early Japanese student, maybe even among the first at Cornell. The student's name was Seikichi Iwasaki."

McKee had brought only a 500-yen coin along on his run, but that was enough to buy the notebook for about four U.S. dollars.

When McKee returned to Cornell, he and University Archivist Elaine Engst began investigating Iwasaki in the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. They found an entry in the 1922 alumni directory listing his name and a Tokyo address; it turned out he'd been at Cornell between 1885 and 1887 and was enrolled in the "science" course of study.

The notebook, however, contained notes from an English class.

Detail view of one of the notebook's pages. Photo: Jason Koski/University Photography.

"His notes were so incredibly detailed that I could see exactly what an English history class in 1886 would have looked like," McKee says. "He took perfect notes, and the extent to which he had really mastered English is amazing, since he was quite young.

"We don't have any other representation like this of the early Japanese students at Cornell," McKee continues. "We have entries in directories and things, but nothing quite this intimate -- nothing to know what a Japanese student actually did while he was here. In representing a very particular group, it's an interesting find."

Finds like these would be impossible without expert librarians' trips abroad. Curators like McKee, who are responsible for the development of international collections that specialized scholars rely on, often take annual trips to buy materials not available in the United States. The diversity of work by Cornell's Asia scholars puts considerable demands on the Asian collections.

In addition to scouring markets and bookstores, McKee meets with dealers, publishers and distributors to find materials. He travels with a binder that contains a list of incomplete series, as well as requests from faculty members, graduate students and other curators looking for hard-to-find Japanese materials.

"I can find good academic books for a few dollars there that would cost 10 times that here, and I can fill in the gaps of our collection," he says. "U.S. distributors just don't provide some of this -- like art catalogs or Japanese hip-hop material. Even some things you can get for free there, like pamphlets that represent human rights organizations, are impossible to find here. These trips are really vital to our work."

Gwen Glazer is the staff writer/editor and social media coordinator for Cornell University Library.

Who was Seikichi Iwasaki? Seikichi Iwasaki, right, with Marjorie Willis Young '22 in 1941. Iwasaki served as a character witness for Young's husband, James R. Young '22, an American journalist charged with espionage in Japan just months before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Photo: Cornell Alumni News/Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. When McKee stumbled across the notebook, he kicked off a quest to discover more about the Japanese student it belonged to in the 1880s. Seikichi Iwasaki (1865-1946) was born into a prominent family in manufacturing. He attended Keio Gijuku (now Keio University), where English language training and progressive Western ideas were emphasized, and left Keio for Cornell in 1885. He spent two years in Ithaca as a graduate student, attended Yale Law School and returned to Japan in 1889. Iwasaki remained connected to Cornell throughout his life. He served for many years as head of the Cornell Club in Tokyo and hosted Cornell alumni on their visits to Japan. In 1940, he bravely stepped up to help a fellow Cornellian: James R. Young '22, an American journalist charged with espionage -- or, "too factual reporting on conditions in China and Japan," as the Alumni News reported in its May 8, 1941, edition. Iwasaki testified on behalf of Young, explaining to a Japanese court, among other things, that fraternities (or "secret Greek clubs") were harmless and innocent. Iwasaki, who was head of the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce and led several businesses, was the only witness who testified at Young's trial, which was held in secret. Many of Young's charges were dismissed. Because he'd already spent 61 days in a secret Japanese jail, he was released on a suspended sentence and moved with his wife, Marjorie E. Willis '22, to New York City. Even though he was a prominent industrial capitalist, Iwasaki maintained a lifelong friendship with the well-known founder of the Japanese Communist Party, Sen Katayama. Iwasaki provided personal support for Katayama by paying off his debts, helping to arrange his marriage and caring for his children when Katayama was forced to leave Japan. It was, in fact, Iwasaki who originally inspired Katayama to study in the United States, where he formed his communist philosophy. |

Additional links

Cornell University Library's Japan collections