CORNELL HISTORY

From elms to brains: Cornellians who gave back in unique ways

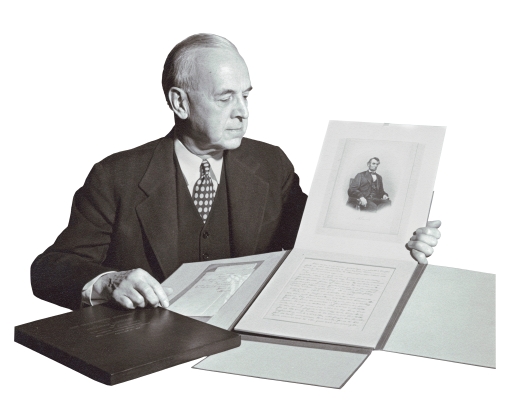

A copy of the Gettysburg Address in Abraham Lincoln's own handwriting, held here by Cornell President Edmund Ezra Day, was given to Cornell by Marguerite Lilly Noyes in 1949.

When Ezra Cornell founded Cornell University with a gift of his land and $500,000 (more than $7 million in today's dollars), he established a legacy of philanthropy that would inspire generations to come. From state-of-the-art laboratory facilities to much-needed scholarship support, gifts of all sizes and types have shaped the university in myriad ways. Much like Ezra's farmland that became the main campus, nonmonetary gifts-in-kind often have a particularly visible or unique impact.

The "Prima inter pares '72" marker by Olin Library ("first among equals") is a tribute to the Class of 1872's gift. See larger image

Perhaps no gift is better known to Cornellians than the Cornell chimes, which have been ringing out over campus since opening day, Oct. 7, 1868. Wanting to do her part to aid Cornell, Jennie McGraw watched her father, lumber merchant and trustee John McGraw, oversee and financially support the fledging university. Founding president Andrew Dickson White, who had grown enamored with carillons and chimes in Europe, suggested to Jennie that a set of bells might be a distinctive and appropriate gift. The original nine bells were played from a wooden stand where Uris Library stands, although they were moved to McGraw Hall in 1873 and finally to McGraw Tower in 1891. Subsequent gifts have enlarged the set of bells from nine to 21, allowing the musical repertoire to expand.

John Ostrander's elm trees (planted in 1877, pictured here in 1953) arched over East Avenue for nearly a century. See larger image

Like Jennie McGraw,local resident John Ostrander was inspired by Ezra's vision and the mission of his new university to educate "any person." A poor farmer, Ostrander offered the best elm trees from his farm. They were planted along East Avenue, providing shade for nearly a century before succumbing to Dutch elm disease. Today, they are remembered with a stone labeled "Ostrander Elms 1880" in front of Stimson Hall.

Ostrander was not the first to contribute elm trees. In fact, one of Cornell's oldest traditions began with a similar gift. When members of the first four-year class graduated from Cornell in 1872, they wanted to express their appreciation for the education and opportunities they received. Their class gift was a double row of 72 elm trees, planted east-west on "President's Avenue" (from East Avenue to the west side of the Arts Quad – the path that President White walked from his home to a stone bench overlooking the slope). Although these elm trees are also long gone, a stone marker remains near the entrance of Olin Library that reads "Prima inter pares '72," which fittingly translates to "first among equals." Continuing the legacy of the Class of 1872, each senior class gives a gift as part of the Senior Class Campaign.

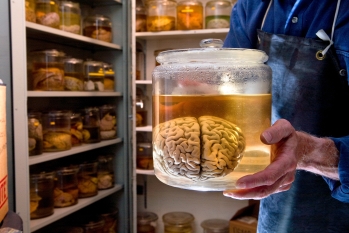

The Wilder Brain Collection was given by zoology professor Burt Green Wilder, who also bequeathed his own brain. See larger image

In 2009, the Sigma Phi Society gave banners representing each college to hang in Willard Straight Hall's Memorial Room. See larger image

A gift of the heart is one thing, but what about gifts of the mind? The Wilder Brain Collection contains some of the most personal gifts received by Cornell. Burt Green Wilder was Cornell's first zoology professor, a former Civil War surgeon who also served as president of the American Neurological Association. Fascinated by the shape and size of brains, he began collecting the brains of particularly educated or notable individuals. In fact, many early faculty members bequeathed their brains to the collection, including psychologist Edward B. Titchener and biologist Simon Henry Gage, as well as Wilder himself. Wilder also acquired the brain of local criminal Edward Rulloff after the murderer became the last person publicly hanged in New York state. Professor Goldwin Smith was less successful in contributing his brain; it was detained at the Canadian border. Women's rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton also willed her brain to the collection, but her family objected and prevented the bequest.

Many of Cornell's collections, especially those in campus libraries, were given to the university by alumni and friends. Perhaps the most valuable item held in the Rare and Manuscript Collections of Kroch Library is the Gettysburg Address, one of only five known copies in Abraham Lincoln's handwriting. The Cornell copy was originally written for historian George Bancroft and passed through his family to grandson Wilder D. Bancroft, a chemistry professor at Cornell, who sold it in 1929. Marguerite Lilly Noyes purchased and returned the document to Cornell as part of an American history collection in 1949 in honor of her husband, trustee Nicholas H. Noyes '06.

The Cornell Chimes began with a gift from Jennie McGraw. See larger image

Unique gifts continue to enrich the student experience, expand research collections and beautify campus today. In 2006, Reed McJunkin '32 contributed a 22-foot-long python skeleton, one of the largest specimens in the world, to Cornell's Museum of Vertebrates, housed at the Lab of Ornithology. In 2009, the Sigma Phi Society provided 13 banners representing each college that hang in Willard Straight Hall's Memorial Room, replacing banners the fraternity contributed in 1990. These gifts, like the chimes and elm trees, remind us that anyone can have an impact on the Cornell experience.

Corey Ryan Earle '07, the 13th Cornellian in his family and a Cornell history buff, is associate director of student programs in the Office of Alumni Affairs.