RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT

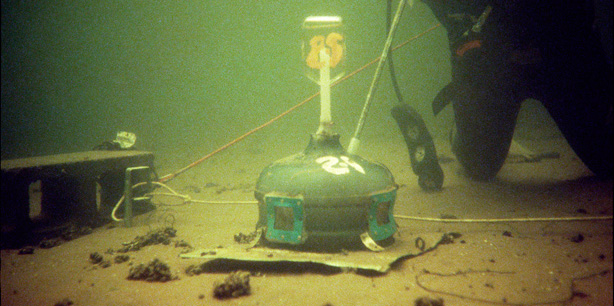

Professor Nelson Hairston takes samples from a sediment emergence trap at the bottom of a lake.

Ecologist studies evolution by bringing century-old eggs to life

Hairston, professor and chair of Cornells Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, studies long-dormant eggs buried in lake sediments. See larger image

Suspending a life in time is a theme that normally finds itself in the pages of science fiction, but now such ideas have become a reality in the annals of science.

Cornell ecologist Nelson Hairston Jr. is a pioneer in a field known loosely as "resurrection ecology," in which researchers study the eggs of such creatures as zooplankton -- tiny, free-floating water animals -- that get buried in lake sediments but can remain viable for decades or even centuries. By hatching these eggs, Hairston and others can compare time-suspended hatchlings with their more contemporary counterparts to better understand how a species may have evolved in the meantime.

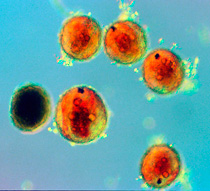

These dormant Daphnia eggs, each about 100 micrometers in diameter, can sit in sediments for hundreds of years and still hatch if returned to the surface (to receive light and oxygen cues to hatch). The eye spot of the reddish embryos is visible in eggs with transparent cases (getting ready to hatch). The brown egg is still dormant. See larger image

The researchers take sediment cores from lake floors to extract the eggs; the deeper the egg lies in the core, the older it is. They then place the eggs in optimal hatching conditions, such as those found in spring in a temperate lake, and let nature take its course.

"We can resurrect them and discover what life was like in the past," said Hairston, who came to Cornell in 1985 and is a professor and chair of Cornell's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. "Paleo-ecologists study microfossils, but you can't understand much physiologically or behaviorally" with that approach, he said.

Hairston first became interested in the possibilities of studying dormant eggs in the late 1970s, when he was an assistant professor of zoology at the University of Rhode Island. There, he noticed that the little red crustaceans -- known as copepods -- in the pristine lake behind his Rhode Island home disappeared in the summer, only to return as larvae in the fall.

The observation prompted him to study why they disappear; his research revealed that the copepods stay active under the ice in the winter, but they die out as their eggs lie dormant on the lake floor through the summer when the lake's fish are most active. When the fish become less active in the fall, larvae hatch from the eggs, and the copepods continue their life cycle.

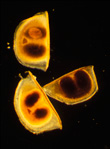

Daphnia neonate emerge from a dormant egg. Approximate size is 300 micrometers. See larger image

This time suspension, when zooplankton pause their life cycles to avoid heavy predation or harsh seasonal and environmental conditions, also increases a species' local gene pool, with up to a century's worth of genetic material stored in a lake bed, Hairston said. When insects, nesting fish and boat anchors stir the mud, they can release old eggs that hatch and offer a wider variety of genetic material to the contemporary population.

In 1999 Hairston and colleagues published a paper in Nature that described how 40-year-old resurrected eggs could answer whether tiny crustaceans called Daphnia in central Europe's Lake Constance had evolved to survive rising levels of toxic cyanobacteria, known as blue-green algae. In the 1970s, phosphorus levels from pollution rose in the lake, increasing the numbers of cyanobacteria. The researchers hatched eggs from the 1960s and found they could not survive the toxic lake conditions, but Daphnia from the 1970s had adapted and survived.

A daphnid, a tiny crustacean that measures 1.2 mm in length. See larger image

Daphnia dormant eggs in specialized pigmented, chitinous cases called ephippia, which are approximately 600 micrometers on the long axis. See larger image

A female copepod carries a bright red egg sac at the base of her body. (Actual size is approximately 2 mm.) These eggs were likely hatched within a few days of this photomicrograph. See larger image

Hairston and colleagues have organized a resurrection ecology symposium this September in Herzberg, Switzerland, to bring together researchers in this growing new field.