PEOPLE

How 'Barbecue Bob' Baker transformed chicken

Bob Baker, professor of poultry science, with students in his food science laboratory on the basement level of Bruckner Hall. Photo provided by Michael Baker. See larger image

The 1950s Ithaca phonebook had listings for three Bob Bakers: a dentist, a debtor and a minor celebrity. Every so often, the wife of the third would get a call trying to collect on debts of the second. "No, no, no," the man's wife (my grandmother) would explain, "this is the home of Barbecue Bob." The mistaken dialer would offer his apologies before telling Jackie Baker how much he admired her husband's recipe.

Such was the fame of Cornell Chicken. By the late '50s, Baker, a professor of poultry science and food science, had brought his recipe to every corner of New York state. In Syracuse, he served it to teeming crowds each summer at the state fair. Cornell Chicken precipitated an unexpected second act of Baker's career, during which he transformed the way we eat chicken.

In 1958, at the height of Cornell Chicken's popularity, Bruckner Hall's basement had been repurposed into a cutting-edge food science laboratory stocked with industrial grinders, elephantine blenders and a custom-made deboning machine. The lab, helmed by Baker, had a simple purpose: to create new foods from poultry.

That it did.

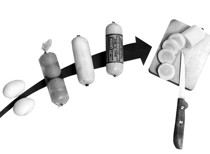

In his first three years, Baker churned out 30 previously unimagined foods. Some, like the chicken hot dog and frozen French toast, were instant hits. Others, like a hard-boiled egg log to be sliced like salami, were not. But Baker's most influential work in Bruckner – atomizing and bridling chicken meat – helped move chicken to the center of the American diet.

Bob Baker, professor of poultry science, in later years. See larger image

When he began his work almost exactly half a century ago, the average American ate fewer than 30 pounds of chicken a year. Now? More than 80. It all goes back to that barbecued chicken.

With his sauce's immense popularity, Barbecue Bob proved that there was an answer to the challenge plaguing poultry scientists: how to get people to eat more chicken.

Poultry departments up and down the East Coast (including, perhaps most notably, Cornell's) had helped make chicken-raising incredibly efficient by the mid-'50s, but those gains had not yet translated into increased consumption. Between 1935 and 1957 chicken production jumped tenfold, but average consumption – despite chicken being cheaper and healthier than red meat – merely doubled and stalled at 30 pounds per person.

Baker produced numerous previously unimagined food products over the years, such as this sliceable hard-boiled egg log. Image provided by Michael Baker. See larger image

The success of Cornell Chicken provided a possible solution: more variety. Surveys found that "chicken fatigue" was hamstringing consumption. Where beef and pork had dozens of guises (chops, steak, hamburger, etc.), chicken was always just chicken; it cooked slowly and got boring fast.

For four decades, Baker ticked off new ways to eat chicken: chicken sausage, chicken bologna, chicken patties. And, inevitably, the precursor to the chicken nugget.

The success of these products signaled a new way for land-grant researchers to use food science to support the state's agriculture industry. Baker proved "that a university could do product development in a way that helped the industry," says Cornell food science professor Joe Regenstein.

Baker shifted his focus to creating new fish products before retiring in 1989. He died in 2006.

Beginning his work at a time when chicken – as a food – was essentially untouched by science, Baker left it, upon his retirement, utterly transformed. When he started, about eight of 10 chickens were sold whole, while two were processed in some way. It is now almost exactly the opposite.

Michael Baker is the grandson of "Barbecue Bob" Baker and is writing a book about him, the chicken nugget and the changing American diet.