VIEWPOINT

Walter LaFeber: A guide, an inspiration

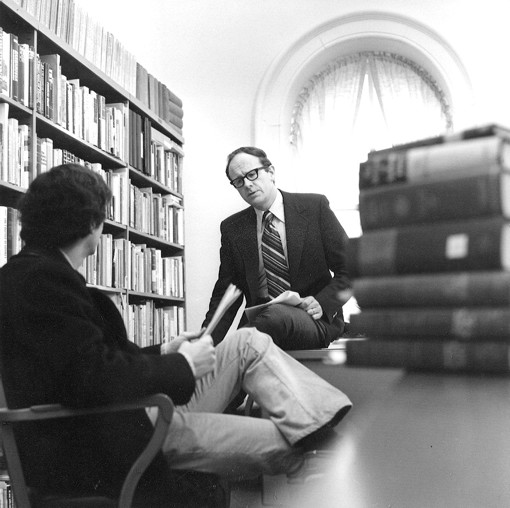

Walter LaFeber with a student in 1973. Photo: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.

I still have the notebook. I bought it for 59 cents at the Cornell Campus Store in fall 1972, as I began my sophomore year. It served for both History 383 (U.S. Foreign Relations, 1776-1914) and, the following spring, History 384 (the sequel), though at the end I ran out of pages and had to clip some more in. The lecture titles are bland – "Polk III," "New Deal to World War II" – but the only doodling in the book illustrates my notes on a guest lecture. No one doodled during a Walter LaFeber lecture.

I became a history major that fall. The traumas of 1969, including the occupation of the Straight, lingered on campus, though Richard Nixon's landslide victory over George McGovern in November seemed last call on the 1960s. The Christmas bombing of North Vietnam provided a paroxysm of violence during winter break; spring term was heralded by the news that a Vietnam peace agreement had been reached in Paris. Another war in the Middle East, the oil shock, and the unraveling of the Nixon administration were months off.

Andrew Rotter '75, a professor of history at Colgate University, right, visits with his former teacher LaFeber, now a Cornell history professor emeritus, in April 2012. See larger image

LaFeber explained it. He explained the sources of the American revolution, the drive for territorial expansion and efforts by James Madison to reconcile a large empire with a good government, the Monroe Doctrine and James Polk's unbridled version of Manifest Destiny, the development of American capitalism and the burst of imperialism that it inspired, then Woodrow Wilson and the Great War and economic diplomacy, World War II and the Cold War confrontation with the Soviets, the engagement with revolution – not our kind of revolution – in Asia, Latin America and Africa. And the Vietnam War. And most everything of historical consequence or political moment in 1972-73. Once, during a political science course discussion of contemporary U.S.-China relations, I asked, more or less innocently, whether the history of the Open Door policy might be of relevance. "LaFeber! Why is it always LaFeber?!" snapped the TA, immediately recognizing yet another student's LaFeber-influenced question.

Why was it always LaFeber? He knew a lot, obviously. His politics were congenial to those of us who hated the Vietnam War, but he was not altogether predictable, either; he was an admirer of conservatives in self-control, suspicious of men of vision that too easily became hubris. There were contrasts in him. He is a tall man with big hands, useful for gesturing, but he spoke calmly and quietly, so the room had to be silent if everyone was to hear him. He wore suits or coats with ties, though during discussion sections he sat casually on the front desk and sometimes ate his lunch. And his rather formal appearance was belied by the radical implications of his words. He never used notes. He walked into the lecture hall, wrote an outline on the board, stuck a hand in his pocket and paced, then began to talk in that quiet way, continuing, for 50 minutes precisely, and ending at the end. The course met Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday mornings, and the Saturday classes were jammed because students brought weekend guests to hear the lecture.

I admired LaFeber, and my other history professors, so much that I couldn't imagine ever doing what they did. I liked the idea of teaching, so I took a couple of education courses and did some student teaching at Ithaca High School. But when I told LaFeber that I was thinking I might teach high school history, he smiled and said, "A good thing to do, but not you. Get a Ph.D. in history, and teach at a university." I nodded, mutely. And, with his help, that is what I did.

It worked, eventually: I am now a professor. I teach courses in U.S. foreign relations, in which I lecture on Polk and the Cold War. I wear ties, write an outline from memory on the board, do some pacing, and sound more radical than I look. But only Walt LaFeber can do it by heart.

Andrew J. Rotter is the Charles A. Dana Professor of History at Colgate University.