COVER STORY

Scene from the Cornell Fashion Collective runway show. Photo: University Communications Marketing.

Eureka! That magic moment of discovery

Science fiction writer Isaac Asimov once said, "The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not 'Eureka!' but 'That's funny …'" True, new ideas don't always hit us with the drama of displaced bathwater rising, as in the exclamation attributed to Greek mathematician Archimedes ("Eureka" means "I have found it!"). In fact, ideas are sometimes not discoveries at all, but compromises or collaborations or slowly dawning truths. Here are some recent Cornell ideas that span inspired revelation, quirky suggestion, counterintuitive supposition and the culmination of a lifetime of careful study.

Scene from Cornell Fashion Collective runway show. Photo: University Communications Marketing. See larger image

1. lighting the runway

At the 30th Cornell Fashion Collective runway show April 12, fashion aficionados glimpsed clothes of the future – sleek laser-cut bodysuits and 3-D printed glasses lined with blue LEDs and electroluminescent wire and tape. The four pieces, developed by fiber science undergraduate Eric Beaudette and Ph.D. student Lina Sanchez-Botero with support from professors Juan Hinestroza and Huiju Park and Toronto-based Myant Capital Partners, imagine "a time when humans and our computers will be more closely integrated," Beaudette says.

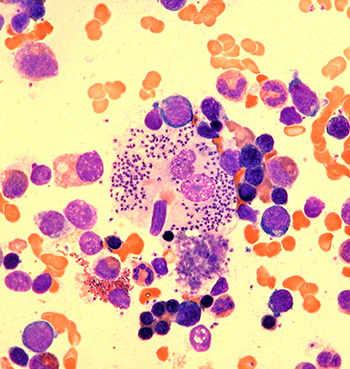

2. beating metastasis with an army of killer white blood cells

Michael King. See larger image

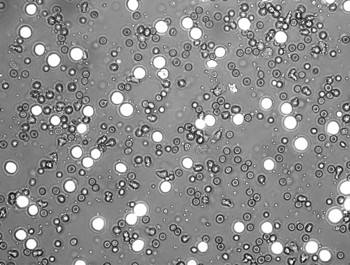

Most cancer deaths – about 90 percent – are related to metastasis, which spreads malignant cells throughout the body. But as Michael King, professor of biomedical engineering, explains, "now we've found a way to dispatch an army of killer white blood cells that cause apoptosis – the cancer cell's own death – obliterating [cancer cells] from the bloodstream. When surrounded by these guys, it becomes nearly impossible for the cancer cell to escape."

In January, King and his colleagues published a research paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The engineers combined a therapeutic protein with an adhesive protein that sticks to leukocytes – white blood cells. When a cancer cell comes into contact with the protein in the bloodstream, it kills itself.

View of metastasis in the bloodstreamage. Image: Michael King. See larger image

King has been conducting studies since 2005, when he tried to scrub blood using a blood-contacting device outside the body. His "eureka" moment occurred a year after moving to Cornell, in 2009, when he decided to "flip the geometry" to see the results of wiping out the cancer from within the bloodstream using nanoparticles.

While at Cornell, King and his colleagues treated cancer cells with the proteins in saline and found a 60 percent success rate in killing the cancer cells. Once the proteins were added to a flowing blood model that mimics human-body conditions, the success rate soared to 100 percent.

Since this new research was published, new mouse trials are underway to test the therapy for prostate cancer. Breast cancer and lung cancer mouse trials will start this summer.

King's colleagues include Chris Schaffer, associate professor in biomedical engineering; Michael Mitchell, a Cornell doctoral candidate in the field of biomedical engineering; Elizabeth C. Wayne, a Cornell doctoral student in the field of biomedical engineering; and Kuldeepsinh Rana, Ph.D. '11.

– Blaine Friedlander

3. algae promise greener energy

Chick with different feedstock choices. Image: Provided. See larger image

It might be green, but is it a moneymaker?

Multidisciplinary Cornell research teams have increased the commercial attractiveness of algal biofuel, overcoming hurdles that have delayed private-sector use of this promising green fuel.

One idea being explored is to develop high-value coproducts at the same time as the algal fuel. Animal scientist Xingen Lei is doing just that. With a new $5.5 million USDA grant to further research launched by Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future seed funding, he is producing a nutritious animal feed from algae for broiler chickens, laying hens and weanling pigs. According to Lei, the animals like the literally and figuratively green alternative to their normal diet.

Also working with algal biofuel, Charles Greene, professor of earth and atmospheric sciences, and his research team parlayed a 2011 Rapid Response Fund award into an international algal biofuel partnership funded by a $9 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy. Algae can produce far more biomass and oil per acre annually than the most productive terrestrial energy crops.

– Sheri Englund

4. holistic and smarter IQ tests

Robert Sternberg. Photo: University Communications Marketing

Saddled with test anxiety, Cornell psychologist Robert Sternberg "failed miserably" on IQ tests as a boy, he recalls. "The school psychologist who gave the tests looked scary, and I would freeze up. Of course, I did poorly. My teachers thought I was stupid. I thought I was stupid. Each year in early elementary school, I did a little worse."

Sternberg eventually overcame his fears, which have fueled one of his life's passions: constructing better intelligence measures. Now a professor of human development in the College of Human Ecology, Sternberg has traveled to remote locations in Africa, Asia, Alaska and elsewhere to develop alternatives to the SAT, ACT and other traditional tests of intelligence.

Traditionally, psychologists believed intelligence could be measured similarly to how a yardstick measures height – as basic mental skills that could be quantified. But Sternberg's research suggests a more holistic view that includes "creative, practical, wisdom-based and ethical skills" that reflect our ability to succeed in our social and cultural contexts.

Working with the Luo people of Kenya, Sternberg and colleagues assessed children's knowledge of natural herbal medicines used in the home. They theorized that if traditional academic measures are an overall indicator of intelligence, children who scored higher on such tests would also excel on tests of local knowledge. However, they found the opposite: For the Luo, having more academic knowledge was not adaptive to life success – local knowledge was. In isolated parts of Alaska and Russia, they made similar discoveries.

– Karene Booker

Cornell MRI Facility in Martha Van Rensselaer Hall. Photo: University Communications Marketing. See larger image

5. the view on shopping sprees from within an MRI

Since opening last year, the Cornell MRI Facility in Martha Van Rensselaer Hall has been a hotbed for unexpected research collaborations, none perhaps more novel than a partnership between neuroscientist Nathan Spreng and fashion design and management researcher Tasha Lewis, both in the College of Human Ecology.

The pair this spring began exploring the biological basis for the popular notion of "retail therapy" – the idea that shopping sprees brighten our outlook.

Lewis hopes she and Spreng could also use the MRI scanner to explore how consumers think about sustainable fashion, another research interest of hers. As with foodies wanting to know about their meal's origins, fashionistas demand to know where and under what conditions a garment was produced.

Spreng, a neuroscientist whose work includes searching for biomarkers to improve early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease, says the facility enables other promising partnerships. He and Peter Doerschuk, professor of biomedical engineering, are developing new methods to view interactions between brain regions in ways never before seen by functional MRI scans. And Cornell linguistics professor John Hale has contacted Spreng to examine the biological basis for speech.

– Ted Boscia

6. have detector. will investigate.

X-ray detector image of accumulation of potassium in the anthers of an iris. Image: Arthur Woll.

Operators of a new X-ray detector at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) had hoped that their March dry run of the device, "Maia," would produce some usable data.

They got that and more. The stunning, high resolution and at times surprising images of ferns, beetles and other objects offered a sneak peek into never-before-seen science.

Maia is an energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence detector. It builds a pixel-by-pixel digital image of X-ray wavelengths, like chemical fingerprints, emanating from the sample. All this at blazing speed, thanks to Maia's ability to process tens of thousands of photons in milliseconds, explains Arthur Woll, CHESS staff scientist.

Bug wings, ferns and feathers examined with Maia so far hint at a bigger role fluorescence detection could play in biological fields.

Take a fern leaf, in which Maia detected potassium, calcium and manganese. Such a striking presence of manganese near the tips of fern veins has never been reported before – a complete surprise to Karl Niklas, professor of plant biology. So, too, was the accumulation of potassium in the anthers of an iris (see image). The technique, Niklas says, could open up a "whole new view" of plant mineral nutrition.

– Anne Ju

7. stop campaigning -- (or, at least don't wear yourself out)

Peter Enns. Photo: University Communications Marketing See larger image

Research from Peter Enns, assistant professor of government, shows that all the money candidates spend on campaign propaganda might not do a thing to sway voters.

Enns analyzed responses from the National Annenberg Election Survey, which is conducted each day of the presidential campaign, and found that voters are much more concerned with "fundamentals" – economic conditions, approval of the incumbent president, partisanship and demographic interests – than campaign propaganda, except very early in campaigns.

"Our results suggest that the campaign plays a much smaller role with these fundamentals than previously thought," Enns says. "This conclusion does not, however, mean that campaigns don't matter. … Looking ahead to 2016, we don't need to wonder if the campaign will get voters to rely on the fundamentals – most can (and will) do this on their own. The real question is whether the campaign (or other events) will get voters to deviate from the fundamentals."

– Kathy Hovis

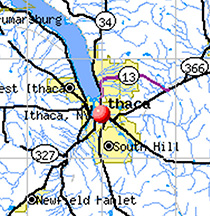

8. local startup ecosystem

Image: Provided. See larger image

The new downtown Ithaca incubator, a collaborative venture among Cornell, Ithaca College and Tompkins Cortland Community College, opened in January, billed as a hub for economic activity in the area that will channel rising entrepreneurs from all three schools into the Ithaca community and surrounding area.

Located in the Carey Building in downtown Ithaca, the incubator is part of the new Southern Tier Innovation Hot Spot, a regional economic development initiative that received a three-year, $750,000 award from the state's Regional Economic Development Council.

The incubator project is being led by Tom Schryver '93, MBA '02, Cornell's newly appointed executive director of new venture advancement.

9. computerized prosthetic eyes that bypass damaged photoreceptor cells

Sheila Nirenberg. Image: MacArthur Foundation. See larger image

MacArthur "genius" fellow Sheila Nirenberg, associate professor of physiology and biophysics at Weill Cornell Medical College, has invented a device that could restore vision via a computerized eyeglass prosthetic.

Nirenberg, who explores fundamental questions about how the brain encodes visual information, developed this alternate approach for patients with photoreceptor cell degeneration (such as those who suffer from macular degeneration and retinitis).

Instead of trying to replace lost photoreceptor cells, Nirenberg's method bypasses the damaged cells entirely and interacts directly with ganglion cells, using neural "codes" generated in response to particular spatial and temporal visual patterns. The prosthetic transmits the codes to the ganglion cells, which then send them to the brain.

10. the growing biz

Feifan Zhou '16, CEO of TuneTap, gives his four-minute pitch to the judges during the second annual Johnson Shark Tank competition on Feb. 4. TuneTap, a service that enables artists and fans to crowdfund live events, won the competition. Photo: University Communications Marketing. See larger image

Every successful business, like any good idea, starts with a seed, that first moment of realization: This could really grow.

Shira Baly '14 got the idea for her company, GummyMed, in a Target store, while passing a shelf of gummy vitamins and wondering why no companies sell drugs in gummy form.

Michael Merrill '17 and Dan Masetti '17 got the idea for their daily coding challenge app, CodeProblems, while hanging out in Willard Straight Hall before a prelim.

Alex Krakoski '16 got the idea for his company, Worthy Jerky, when he made enough money selling homemade beef jerky out of his backpack at his high school in the Swiss Alps to pay for a trip around Europe. Arriving at Cornell the next year, Krakoski found many campus resources (classes, advice, contests, funding) to help entrepreneurial projects and started to grow his business. "It was an easy choice to pursue it further," he says.

Krakoski gained valuable perspective from professor Dan Cohen's Introduction to Entrepreneurship course in ILR, and he has worked with professors in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences extensively. eLab, Cornell's startup accelerator based at the Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management, has given him and his growing team access to veteran entrepreneurs and professors.

Worthy Jerky has matured from concept to business, with deals in place with several Ithaca stores and an e-commerce platform to take orders online. GummyMed and CodeProblems, both in development, won recognition at the Big Idea Competition in April.

Cornell has an atmosphere that encourages students to come up with new business ideas, and nurtures those new businesses, says Zach Shulman, director of Entrepreneurship@Cornell, a universitywide effort that helps students, faculty, staff and alumni find resources to start businesses, some in partnership with the Student Agencies Foundation.

– Kate Klein

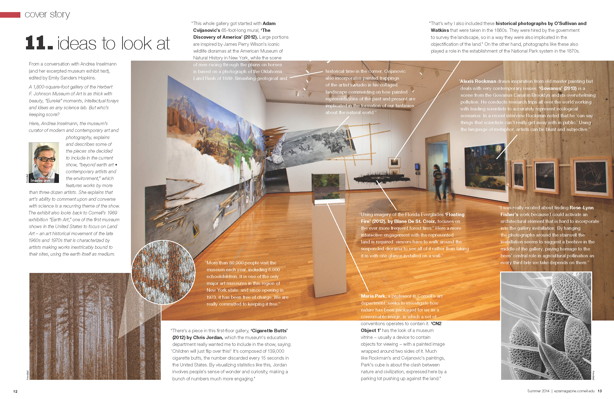

11. ideas to look at

Johnson Museum view of "beyond earth art" exhibit with labeled items of interest click for large view. Photo: University Communications Marketing (Click for large view)

From a conversation with Andrea Inselmann (and her excerpted museum exhibit text), edited by Emily Sanders Hopkins.

A 1,800-square-foot gallery of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art is as thick with beauty, "Eureka" moments, intellectual forays and ideas as any science lab. But who's keeping score?

-

Here, Andrea Inselmann, the museum's curator of modern and contemporary art and photography, explains and describes some of the pieces she decided to include in the current show, "beyond earth art

- contemporary artists and the environment," which features works by more than three dozen artists. She explains that art's ability to comment upon and converse with science is a recurring theme of the show. The exhibit also looks back to Cornell's 1969 exhibition "Earth Art," one of the first museum shows in the United States to focus on Land Art – an art historical movement of the late 1960s and 1970s that is characterized by artists making works inextricably bound to their sites, using the earth itself as medium.

Andrea Inselmann. Photo: Johnson Museum See larger image

"This whole gallery got started with Adam Cvijanovic's 65-foot-long mural, 'The Discovery of America' (2012). Large portions are inspired by James Perry Wilson's iconic wildlife dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, while the scene of men racing through the plains on horses is based on a photograph of the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889. Smashing geological and historical time in the corner, Cvijanovic also incorporates painted trappings of the artist's studio in his collaged landscape commenting on how painted representations of the past and present are implicated in the formation of our fantasies about the natural world."

"That's why I also included these historical photographs by O'Sullivan and Watkins that were taken in the 1860s. They were hired by the government to survey the landscape, so in a way they were also implicated in the objectification of the land." On the other hand, photographs like these also played a role in the establishment of the National Park system in the 1870s.

"Alexis Rockman draws inspiration from old master painting but deals with very contemporary issues. 'Gowanus' (2013) is a scene from the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn and its overwhelming pollution. He conducts research trips all over the world working with leading scientists to accurately represent ecological scenarios. In a recent interview Rockman noted that he 'can say things that scientists can't really get away with in public.' Using the language of metaphor, artists can be blunt and subjective."

"More than 80,000 people visit the museum each year, including 8,000 schoolchildren. It is one of the only major art museums in this region of New York state, and since opening in 1973, it has been free of charge. We are really committed to keeping it free."

"There's a piece in this first-floor gallery, 'Cigarette Butts' (2012) by Chris Jordan, which the museum's education department really wanted me to include in the show, saying: 'Children will just flip over this!' It's composed of 139,000 cigarette butts, the number discarded every 15 seconds in the United States. By visualizing statistics like this, Jordan involves people's sense of wonder and curiosity, making a bunch of numbers much more engaging."

"Using imagery of the Florida Everglades 'Floating Fire' (2012), by Blane De St. Croix, focuses on the ever more frequent forest fires." Here a more interactive engagement with the represented land is required: viewers have to walk around the suspended diorama to see all of it rather than taking it in with one glance installed on a wall."

"Maria Park, a professor in Cornell's art department, seeks to investigate how nature has been packaged for us as a consumable image, in which a set of conventions operates to contain it. 'CN2 Object 1' has the look of a museum vitrine − usually a device to contain objects for viewing − with a painted image wrapped around two sides of it. Much like Rockman's and Cvijanovic's paintings, Park's cube is about the clash between nature and civilization, expressed here by a parking lot pushing up against the land."

"I was really excited about finding Rose-Lynn Fisher's work because I could activate an architectural element that is hard to incorporate into the gallery installation. By hanging the photographs around the stairwell the installation seems to suggest a beehive in the middle of the gallery, paying homage to the bees' central role in agricultural pollination as every third bite we take depends on them."

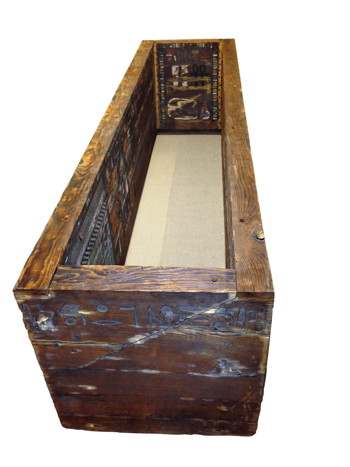

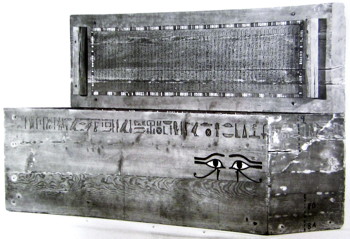

Egyptian coffin. Photo: Sturt Manning. See larger image

12. tree rings provide insight

A handful of tree ring samples stored in an old cigar box have shed unexpected light on the ancient world, thanks to research by archaeologist Sturt Manning and collaborators at Cornell and in Arizona, Chicago, Oxford and Vienna.

The samples were taken from an Egyptian coffin; Manning also examined wood from funeral boats buried near the pyramid of Sesostris III. He used a technique called dendro radiocarbon wiggle matching, which calibrates radiocarbon isotopes found in the sample tree rings with the patterns known from other places in the world.

Because the dating was so precise – plus or minus about 10 years – it helps confirm that the "higher" Egyptian chronology for the time period is correct, a question scholars have hotly debated.

But the samples also showed a small, unusual anomaly following the year 2200 B.C., when paleoclimate research has suggested that there was a major short-term arid event about this time.

"This radiocarbon anomaly would be explained by a change in growing season, i.e., climate, dating to exactly this arid period of time," says Manning, the Goldwin Smith Professor of Classical Archaeology and director of the Malcolm and Carolyn Wiener Laboratory for Aegean and Near Eastern Dendrochronology. "We're showing that radiocarbon and these archaeological objects can confirm and in some ways better date a key climate episode."

Egyptian coffin detail. Image: S. Cristanetti, A. Whyte/Oriental Institute, University of Chicago. See larger image

That climate episode, says Manning, had major political implications. There was just enough change in the climate to upset food resources and other infrastructure, which is likely what led to the collapse of the Akkadian Empire and affected the Old Kingdom of Egypt and a number of other civilizations.

"The tree rings show the kind of rapid climate change that we and policymakers fear," says Manning. "This record shows that climate change doesn't have to be as catastrophic as an Ice Age to wreak havoc. We're in exactly the same situation as the Akkadians: If something suddenly undid the standard food production model in large areas of the U.S., it would be a disaster."

– Linda B. Glaser

Parking meter. Image: Amanda Rohde/Hidesy. See larger image

13. let's pay more for parking

According to Michael Manville, assistant professor in City and Regional Planning, municipalities would be wise – and richer and more efficient and more pleasant to live and drive in – if they established market-based street parking rates.

The price of street parking should vary by block and time of day, with the aim of always keeping one to two spaces open on every block. Charging the right price for parking would deliver a better service to drivers – by ensuring they always find an open space – and also encourage more walking, cycling and transit use. Not least, it would raise revenue (without raising taxes) that cities could spend on services that residents value.

"Cities everywhere give away valuable land to drivers," Manville says. "Ending this quiet but huge subsidy will help the environment, the economy and the transportation system."

– Emily Sanders Hopkins

14. journal club

Image: Journal of Neuroscience See larger image

Monday in Mudd Hall is neurobiology and behavior journal club day, led by professors Kerry Shaw and Carl Hopkins, both in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior. Hopkins had the idea for journal club, introduced in 2011, which asks undergraduate students to dive into the very latest research before they have mastered the fundamentals of biology and scientific research.

"Somehow," Hopkins explains, "the fact that the student is learning about something that most people in the university don't know about gives them a special feeling of being in the in-group. Since the results are so new … students are allowed to wonder if the data are solid, if the experiments are properly controlled."

After they've selected a paper to study out of hundreds published every month, students must analyze and make an oral presentation (with slides) on the new research.

"The students learn a great deal grappling with the primary literature and take away lifelong lessons on how to evaluate the newest scientific research," Shaw says.

Recent papers have covered how smell activates appetite; a neural mechanism of first impressions; phonetic feature encoding in the human brain; and why bonobos share with strangers.

– Emily Sanders Hopkins

Hadas Kress-Gazit. Photo: University Communications Marketing. See larger image

15. robots with better listening skills

Hadas Kress-Gazit, assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, is teaching robots to understand "natural language," turn it into the detailed instructions they need, and if necessary, tell their human handlers if there's a problem.

A software package called SLURP (Situated Language Understanding Robot Platform) starts by checking words in your command against a database of verbs and the qualifiers that go with them. For example, if you say, "Go to the kitchen and get me a glass of milk," it knows that "to" labels a destination for "go." The language processor hands off to software that converts the English words into steps in "linear temporal logic," a language that includes symbols for concepts like "until," "while," "always" and "never," which in turn lead to standard computer programming steps like "if … then," and the robot creates a short temporary program for the job it has to do.

Robot used for natural language processing. Photo: University Communications Marketing. See larger image

Of course science fiction is full of uncooperative robots. "That does not compute" is a familiar catchphrase. The nonexpert robot handler needs that feedback to give better instructions or fix whatever might get in the way. Kress-Gazit's software runs through the steps the robot has planned and checks each one for feasibility. If there's a problem, it composes a natural language reply by combining part of the original command with a few words of explanation like, "I can't get you a glass of milk. We're out of milk." The robot also will check the actions against a list of rules: "I can't get you a glass of milk because the cat is sleeping in the hall and you told me never to frighten the cat."

The next step in the research will be to equip the robot to suggest solutions: "Do you want me to order milk?" By the time we have personal robots it might be, "The refrigerator has ordered milk; it should be delivered in about an hour." And by that time, cats will probably be used to robots.

– Bill Steele

16. how many butterflies have you really seen?

Monarch butterfly. Photo: Anurag Agrawal

Evolutionary ecologist Anurag Agrawal's idea was sparked in 2012 at the Monarch Biology and Conservation conference, which attracted some 200 butterfly enthusiasts – academics, conservationists and hobbyists.

There, participants debated two recently published yet conflicting papers: One study reported a decline of monarch populations over the past 18 years, while another study analyzed those same years but found no such declines. During discussions, Agrawal noticed that some participants disregarded science that didn't agree with their personal views.

That was when Agrawal first conceived of a project – funded by a 2013 Academic Venture Fund seed grant from Cornell's Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future – to shed new insight on the debate of whether monarchs are indeed in decline, through a rigorous mathematical analysis of nearly 40 years of citizen science data of monarch counts in North America.

And with all censuses showing the last three years having the lowest monarch populations on record, Agrawal and colleagues hope to better understand the causes behind the population trends.

In addition, Agrawal will work with environmental sociologists (including Cornell faculty members Steven Wolf and Bruce Lewenstein) to clarify what the butterflies represent for people – how messaging about monarchs occurs, and how ambiguous scientific information is used by environmental organizations, for example.

Monarch butterflies have "become iconic because their story is so remarkable," including their cross-continental migrations, the toxins monarchs sequester from milkweeds, and their ubiquity in American childhoods, Agrawal says.

– Krishna Ramanujan

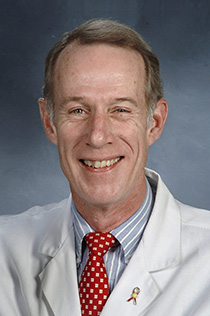

17. single-dose cure for disease

View of parasitized macrophage in bone marrow. Image: Henry Murray. See larger image

Henry Murray '68, M.D. '72, is an infectious disease and tropical medicine specialist and the Arthur R. Ashe Professor of Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College. He has spent the last 30 years working on leishmaniasis, a parasitic infection found worldwide, particularly in India, that is spread human-to-human by the bite of sandflies.

Murray's life's work on leishmaniasis recently culminated in the development of two effective treatments for the disease.

In March, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted fast-track approval of oral miltefosine (trade name: Impavido), a treatment for the three forms of leishmaniasis that Murray's effort helped bring to clinical fruition. It is the first effective oral treatment for the disease.

But Murray's "Eureka!" moment happened in 2000; it has led to the single-dose intravenous treatment using liposomal amphotericin B (trade name: AmBisome) that has dramatically changed how the visceral form of infection is managed in the Indian subcontinent.

Dr. Henry Murray. Photo: Weill Cornell Medical College See larger image

Untreated visceral leishmaniasis is fatal. As many as two-thirds (about 200-250,000) of the world's new cases each year appear in a New England-sized region of the Indian subcontinent that includes the northeast state of Bihar, part of Bangladesh and southern Nepal, where it causes an estimated 20,000-25,000 deaths per year.

Visceral leishmaniasis (called kala-azar, "black fever," in the region) "has always been there in near- or true-epidemic form," Murray says. A treatment to greatly reduce or potentially eliminate the disease would need to be well-tolerated, highly effective and efficient, require no lab testing, guarantee 100 percent compliance and able to be administered in a rural health center setting. Tens of thousands of patients would need to be treated.

Lipid formulations of drugs, including liposomal amphotericin B, that came on the scene in the 1990s made it possible to target the actual cells in which the parasite multiplies. The treatment trials unit Murray helped to establish in India had already used this drug to dramatically improve and shorten kala-azar treatment from 28 to 5 days. Murray's idea was to find a way to roll the treatment into a single intravenous dose – a regimen that would need to be safe and as effective as multiple-dose therapy.

The first single-dose trials reached about a 90 percent cure rate (the acceptable benchmark is 95 percent). By the time of a third study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2010, they had reached 96 percent.

"It took us 10 years to come up with a regimen which ultimately has changed the face of treatment in the Indian subcontinent," Murray says. Also gratifying: Murray's regimen is at the core of the National Kala-Azar Elimination Program shared by India, Bangladesh and Nepal; its goal is to essentially eliminate the disease, reducing its prevalence from 30-35 new cases per 10,000 population each year to fewer than 1.

– Joe Wilensky

18. love, not war

Image: Carla DeMello.

Why compete when we can collaborate?

That's the question Anne Kenney – Cornell's Carl A. Kroch University Librarian – asked in February 2009, after an unproductive meeting with a big group of research libraries.

All the libraries were slammed by a major recession, shrinking budgets, skyrocketing journal prices and increased demands for specialized content and expert librarians.

Later that year, Cornell and Columbia formed an unprecedented partnership between two Ivy League libraries: 2CUL – pronounced "too cool," for two libraries with the same "CUL" acronym.

Five years later, the two libraries collaborate on a range of initiatives, plans and programs, with support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and the partnership is working for both institutions.

Together, Cornell and Columbia are creating purchasing and licensing agreements to negotiate better deals with publishers and vendors; developing infrastructure to support sharing expertise and specialized subject areas; improving programming for humanities Ph.D. students; and developing strategies for preserving e-journals.

Cornell and Columbia students and faculty now have access to each other's physical facilities, so a Cornellian can get a Columbia library card, walk into Butler Library in Manhattan and borrow a book.

How's that for peace, love and understanding?

– Gwen Glazer

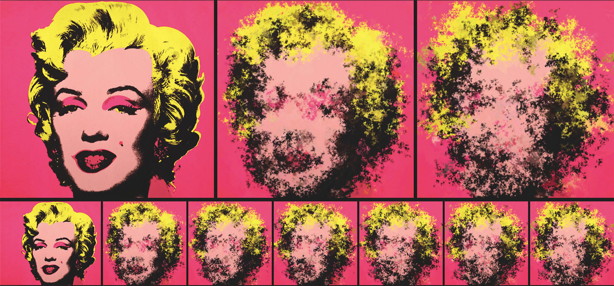

19. see music, hear architecture: a fruitful collaboration

"after [no title] by Warhol, 1967" (2014), from Taylan Cihan and Andrew Lucia's exhibit "Portraits," which uses Lucia's algorithm to transform and reorder still images. Image: Andrew Lucia

Musician and doctoral candidate Taylan Cihan recently picked up some architectural blueprints and saw music.

They were the plans for a building designed by architect Andrew Lucia, a lecturer in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning – yet Cihan realized then that a blueprint is very much like a musical score.

"It is one hundred percent identical," he says, "a representation of a very complex phenomenon." A set of blueprints deals with material in much the same way that a musical score deals with sound.

Cihan and Lucia now work together to find common patterns and processes that underlie their different disciplines. Their groundbreaking ideas on musical and visual art have led to several fruitful collaborations.

The partnership started incidentally in 2012, when Lucia ran into some technical trouble with a sound visualization piece he was creating. Cihan helped him with the equipment needed to create a visual display from the sound of a viola de gamba quartet and liked the work he was doing.

"A couple weeks later," says Cihan, "we were playing our first show."

Their first live improv "noise" piece was presented during a Cornell Contemporary Chamber Players concert; in May 2012, the Cornell Symphony Orchestra premiered "An," a piece by Cihan accompanied by a visualization by Lucia.

To compose the piece, Cihan ran a violin bow across the edge of a cymbal, created a computer-aided spectral analysis of that sound and re-orchestrated it for symphony orchestra. To create the visual display, Lucia wrote an algorithm inspired by Cihan's process. The result was an evolving white, black and colored field whose edges dance like flames to the pulse of the music.

Their real creation, they said, is not the sound or the image but the generative process that creates both the visual art and the music.

The duo also shared their ideas with students by co-teaching a spring course, Sound and Image: Studies in Production and Affect, that challenged students to develop creative audiovisual projects.

– Kate Klein

20. shop global (for professors)

The first cohort of International Faculty Fellows: From left, Saurabh Mehta, Andrea Bachner, Daniel Selva and Victoria Beard. Photo: University Communications Marketing. See larger image

Infectious diseases; maternal and child health in Africa; community-based planning and poverty in Southeast Asia; theories of cultural differences in China; and the development of remote sensing satellites are at the heart of research by some of Cornell's most talented junior faculty. This summer, Saurabh Mehta, nutritional sciences (College of Human Ecology); Victoria Beard, city and regional planning (College of Architecture, Art and Planning); Andrea Bachner, comparative literature (College of Arts and Sciences); and Daniel Selva, mechanical and aerospace engineering (College of Engineering), begin three-year terms with the Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies as the first cohort of International Faculty Fellows (IFF).

They are expected to contribute to the intellectual life of Einaudi by hosting workshops in their fields of study. They will interact with various international programs housed within the center and enjoy opportunities to work across disciplines.

This new initiative is a centerpiece of Vice Provost for International Affairs and Einaudi Center Director Fredrik Logevall's "Call to Action: Advancing Cornell's International Dimension." It is meant to foster new collaborations between the colleges and the Einaudi Center, to enhance the connectivity of internationalization across campus, and to assist Cornell's colleges and schools with recruitment and retention of superb faculty whose research and teaching has an international focus.

– Laurie Damiani

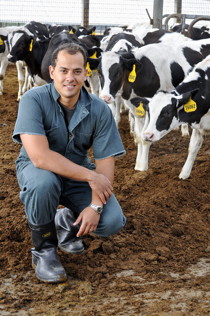

21. the first metritis vaccine

Photo: Lexy Roberts See larger image

One of the most common cattle diseases, metritis, affects about a quarter of the roughly 9 million dairy cows in the United States and causes a domino effect of harm. Metritis sickens cows and makes them less productive; cuts into farmers' profits; and because of the widespread use of antibiotics to combat metritis, there is a serious impact on human public health: Antibiotics given to cows pollute the groundwater and milk supply and contribute to the growing epidemic of antibiotic resistance.

"Our lab has been developing a vaccine for years now based on our research of this disease," says Rodrigo Bicalho, assistant professor of dairy production medicine at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Rodrigo Bicalho. Photo: Stephanie Specchio. See larger image

Happily, the work has led to results even better than expected. Cornell scientists, with funding from Merck Animal Health, have created new vaccines that can prevent this infection of the uterus from taking hold and reduce its symptoms when it does, a prospect that could save the United States billions of dollars a year and help curb antibiotic resistance.

Metritis develops after a cow gives birth, when bacteria take advantage of the open vagina and cervix to settle in the uterus. Infected cows suffer fever, pain, inflammation, lack of appetite, depression and reduced reproductive abilities. It is the No. 1 cause of systemic antibiotic use. Three of the vaccines Bicalho's lab created decreased metritis incidence from 49 to 83 percent and lessened its symptoms when it did infect cows that received the vaccination.

"The powerful protection these vaccines produced surprised us. We expected some protective effect but nothing as strong as what we found," said Bicalho, who is working to move the vaccines toward USDA licensing.

– Carly Hodes

22. mentors matter

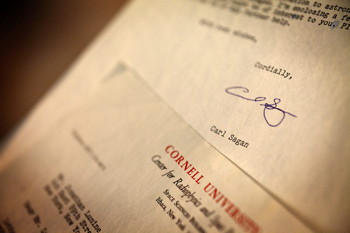

Jonathan Lunine with one of the letters he received from Carl Sagan when Lunine was a high school student. Photo: University Communications Marketing See larger image

Jonathan Lunine (pronounced Loo-NEEN) holds the David C. Duncan Professorship in the Physical Sciences, the chair once held by Carl Sagan. He is director of the Center for Radiophysics and Space Research and lead investigator on a mission to send a probe into Saturn's atmosphere. He also is a co-investigator on NASA space mission Juno and interdisciplinary scientist on Cassini. Last year, Lunine's work led to the first measurement of the depth (400 feet) of a liquid methane sea on Titan. Lunine is a science adviser to "Cosmos," the new Fox television series based on Sagan's 1980 PBS series.

In this interview with Ezra contributing editor Emily Sanders Hopkins, Lunine recalls that beginning in the 1970s, he and Sagan exchanged several letters:

So there I was in New York City. … My father died in 1974. He was an alcoholic. It was a pretty dark and dismal time. After every chapter [of Sagan's book "The Cosmic Connection"], I would go to my mother and say, "I need to read this part to you." She finally got fed up and said, "Why don't you write to him?" and I said … "Well, he wouldn't write back to me! He's a famous professor at Cornell and I'm just a high school student."

But I did write him a letter. Sometime later, I got a letter back from him. It was actually a package in a manila envelope, which I still have, and it contained the letter and two reprints of scientific articles on his studies of the Martian moons Phobos and Deimos with data from Mariner 9, the first mission to orbit Mars. I was thrilled.

I'd asked him how one could become an astronomer, what should you study in high school, and what are the good places to go to college to major in astronomy. And he wrote and told me all about what to do. … I then wrote to him a couple of more times. And he wrote me back.

Letters Carl Sagan wrote to Jonathan Lunine when Lunine was a high school student. See larger image

Unbeknownst to me, in 1987 my mother then wrote to [Sagan]. By that point I'd gone to college at Rochester and graduated with a Ph.D. from Cal Tech, and I was a faculty member at Arizona. And I think my mother couldn't contain her desire to write … to tell him I'd really become an astronomer. He wrote back to her. It's dated March 18, 1987.

Dear Mrs. Bean,

I want you to know how much I appreciate the letter you sent me last December. The accumulation of mail has now reached such a state in my office that I am not answering as many of the letters from younger versions of Jonathan Lunine as I should. And among many other things, your letter reminds me of the importance of finding ways to write to youngsters. I know and admire your son's planetary research sufficiently that we made a serious effort to attract him to an assistant professorship here at Cornell. And if I have helped inspire Jonathan and taught him something about planetary science, he has certainly returned the favor.

With warm good wishes, cordially,

Carl Sagan.

That letter is actually the one I treasure the most.

It was his unbridled visionary enthusiasm that transported so many people into the universe with Carl. … we are doing things today Carl envisioned and wished we could do: exploring planets around other stars, seeing if they have atmospheres suitable to support life, mapping seas of another world, discovering liquid water environments deep in the interiors of Saturnian moons … That which he imagined humankind could do and should do are the things that will carry us across many generations into the cosmos as a spacefaring species. Those of us inspired by Carl need to continue articulating that vision.