COVER STORY

Photo illustration

West Coast Cornell(ians):

Snapshots of a dynamic relationship between Cornell and its West Coast community

In spring 1975, John Williams '74 bought a $69 bus ticket to California. He carried with him little more than a new degree in cheese making from Cornell, four years of work-study experience with Taylor Wine Co. in Hammondsport, New York, and the address of a Cornell friend's brother.

When Williams got to the address in Napa Valley, no one was home. In fact, he says, the place looked abandoned.

He pitched a pup tent in the front yard and went to sleep.

He had traveled across the continent with dreams of joining a California wine industry that, in the mid-1970s, was just beginning to emerge from a long slumber brought on by Prohibition.

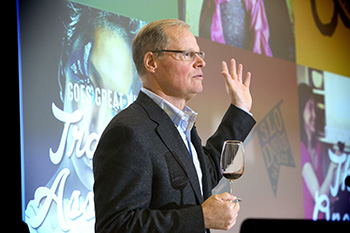

John Williams '74. See larger image

The son of upstate New York dairy farmers, Williams discovered winemaking almost by accident; when his scholarship ran out during his sophomore year in Cornell's College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, he started the only work-study position he could find, at an upstate winery.

"I'd never had a glass of wine in my life," says Williams.

Taylor Wine was a new atmosphere for him – the fermentation tanks, the attractive women serving wine – and he liked it. He worked four years at the winery, majored in food science with a specialty in cheese fermentation (which shares the basics of winemaking) and caught that bus to Napa Valley.

By the time he woke up the next morning, his host, Larry Turley, a doctor who practiced in nearby Santa Rosa, had returned home. He invited him in.

The two became fast friends and wine pioneers; Turley introduced Williams around and Williams soon became the first employee at Stag's Leap Wine Cellars, which would become an important player in the history of California wine.

Williams was the only employee of Stag's Leap when the winery participated in the historic 1976 Judgment of Paris winetasting competition. The Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon won in the red category and a Chardonnay from another Napa winery, Chateau Montelena, won in the white category, showing the world that California wine was on a par with French, jump-starting the industry (and inspiring the 2008 film "Bottle Shock").

"I was there when Napa Valley awoke," Williams says. He and Turley started Frog's Leap Winery in 1980, using cash raised by selling their motorcycles. When Turley started his own winery in 1993, Williams and his family took full ownership.

Now Frog's Leap Winery is known all over the world. Williams' favorite part of work is still growing the grapes and making the wine.

"I'm the ultimate aggie in that way," he says, explaining that his love of winemaking and his Cornell education are "linked hand in hand, for sure."

Nearly 30,000 Cornell alumni live and work in California, Oregon and Washington, and it's a vibrant community of alumni, parents and friends, says Jim Mazza '88, associate vice president for alumni affairs.

But does it matter whether Cornellians are living and flourishing in any given place?

According to Jim Morgan '60, MBA '63, a Cornell University Presidential Councillor and former CEO and chairman of Applied Materials, a global semiconductor, display and solar equipment company based in California, it matters a great deal.

"We believe that Cornell is a very unique university at this particular time," says Morgan, "because of its in-depth capabilities in every college. This combination of quality and diversity of studies within the university isn't really happening anywhere else in the world."

If a university wants to contribute solutions to the world's major problems such as political instability and environmental degradation, it needs to have feet on the ground where solutions are burgeoning, Morgan points out. "The real activity and momentum," he predicts, "is on the West Coast and [in] Asia. So it's really important that Cornell be there in strength.

"For the next 20 years, that's going to have the most impact on education, job opportunities and fundraising."

In 1999, Cornell President Frank H.T. Rhodes reached out to a handful of West Coast Cornellians for advice on fostering engagement in the region. One of those people was university trustee emeritus Ann Bowers '59.

"'I want you to tell me,' Bowers remembers Rhodes saying, 'what Cornell looks like from the West Coast.' That was how this group got started." The resulting Cornell Silicon Valley advisory group has continued to advise subsequent Cornell presidents on potential trustees, industry trends, policy and politics, and launched the popular and influential Cornell Silicon Valley (CSV), which hosts programs large and small for tech industry networking and alumni engagement.

"With the West Coast being home to the second-largest concentration of alumni after those living in the Northeast Corridor, our partnerships with West Coast alumni have been and continue to be vitally important," Mazza says.

Padmasree Warrior, M.Eng. '84. Image: Jamie Tanaka Photography. See larger image

Gateway to success

In spring 2014, the CSV event "The Future is Cornell" had as its keynote speaker Cornell trustee Padmasree Warrior, M.Eng. '84, CTO and chief strategy officer for Cisco Systems.

"She's the only woman in the valley who is running the technology side of anything that big," Bowers says.

In 1982, Warrior was a young technical college graduate from India who came to do graduate work in chemical engineering at Cornell thanks to a scholarship. "I often tell people," says Warrior, "that I came to America with $100 and a one-way ticket. I appreciate the opportunity that Cornell gave me. Cornell is something I'm very attached to. It was sort of the gateway to my success. That's why I'm a trustee." Warrior joined the board in 2013 and serves on the student life, academic affairs and development committees.

While she was pursuing her Ph.D. at Cornell, Motorola came to Ithaca and recruited Warrior. She'd earned a master's degree and begun work on her doctoral dissertation. "I thought I would go finish my Ph.D. eventually," Warrior remembers. "Professor Rodriguez every Christmas would send me a card and gently remind me that I needed to finish." But as she rose through the ranks of Motorola and joined Cisco, his annual reminders became something of a joke between them. She didn't have the time or the need for a doctoral degree, it seemed.

Last year, Warrior was ranked the 71st most powerful woman in the world by Forbes.

"I'm pleasantly surprised how active the Cornell network is," says Warrior. "At Cisco, we have a large number of Cornellians. Lew Tucker '72, one of our CTOs, is a Cornellian. We recruit a lot from Cornell. We really look at talent that can combine the tech and business savvy with people skills."

Warrior's people skills are legion. "In a typical day, I spend time with customers, startups, venture capitalists, CEO-level folks from partner agencies and I mentor – a lot of one-on-ones with people in our company."

"I'm first and foremost a technologist," Warrior says. "I'm an engineer, but I'm also really an extrovert. I love mentoring, and I measure my success on how successful I make other people look. Making my peers, my bosses, the people who work for me look good."

Authentically hands-on

Mort Bishop '74, president of Pendleton Woolen Mills in Portland, Oregon, learned business skills in CALS and theory in the College of Arts and Sciences, but partway through his four years, one gap in his knowledge suddenly struck him as unacceptable: "I said to myself, I'm a fifth-generation member of the Pendleton Woolen Mills family. I need to learn to shear a sheep."

Mort Bishop '74. Image: Courtesy Pendleton Woolen Mills. See larger image

The manager of Cornell's sheep herd agreed to tutor Bishop in the art that is the basis of every Pendleton wool product. "The poor first sheep was a bit bloodied," says Bishop, remembering the difficulty of the lesson, "but that helped authenticate my Cornell experience."

When he reflects on his time as a student, lightweight crew is one of Bishop's dearest Cornell memories. The regimen of physical exercise and "rowing on Cayuga Lake with the geese and seeing the Cornell Tower" has stayed with him through the years. He is a strong supporter of Cornell rowing, and he hopes that the money he donates translates directly into current student-athletes experiencing some of those geese and tower moments. He also donates a Pendleton wool blanket to every varsity team captain.

Bishop is scholarship chair of the Cornell Club of Oregon and Southwest Washington, which formed in 1980 to help students from Oregon. The CCORSW Scholarship Fund, valued at $2 million, grew little by little, says Bishop, as Oregonians designated their Cornell Fund gifts to the scholarship effort. Today it's the largest club scholarship at Cornell.

In April, Bishop and his wife, Mary Lang, welcomed all accepted Portland members of the Class of 2019 to their house for a reception, a tradition the couple has kept up for 30 years.

From acceptance and matriculation to graduation and life as alumni, West Coast Cornellians share a special bond, says Bishop.

"We can't take Cornell for granted," he says. "We can't get back as often as people who live closer can. We have to create the Cornell experience where we are."

A good example

What you often find when you speak to faraway Cornellians who make a point of staying in touch with their alma mater is gratitude – for a particular mentor, for a set of knowledge they gained, for their college friendships or one favorite class that changed their life.

As president of Nintendo America, Reggie Fils-Aimé '83 is known as a dynamic presence and charismatic speaker. He's known in the gaming world as "the Regginator," and quotes from his speeches have gone viral online. "My name is Reggie," he announced at the 2004 Electronic Entertainment Expo. "I'm about kickin' ass, I'm about takin' names, and we're about makin' games." He appeared as an animated character fighting global Nintendo President Satoru Iwata at the 2014 E3 conference in Los Angeles.

Reggie Fils-Aimé '83. Image: Scott Eklund/redboxpictures. See larger image

His passion for public speaking, he says, was inspired by economics and management professor Richard Aplin, for whom he worked as a grader and teaching assistant.

"I watched him work incredibly hard to create and then deliver over two years of lectures," Fils-Aimé says. "Imagine: he had been teaching these classes over a number of years. He knew the material cold – even when new material was added into the curriculum. But he would prepare as if he were delivering the lecture for the very first time. I think this reinforced my focus on preparation and passion for public speaking."

Fils-Aimé returns to the Ithaca campus as a member of the Department of Communication's advisory council, he frequently participates in West Coast alumni events, and he has been a speaker for the Cornell Entrepreneurship Network (CEN).

"Everyone [at CEN] has a passion to learn, and a passion to give back to the university," he says.

Hard, but worth it

Cornell was a hard school and a place where "you were pretty much on your own," remembers Jon Rubinstein '78, M.Eng. '79, a self-described "born engineer" who picked up his first screwdriver at age 2 and went on to become the primary architect of the iMac and the iPod. "You were responsible for yourself," he remembers. "I mean, there were people who would help you if you needed help. But I think it required a level of independence that fostered a sense of self-sufficiency."

The son of a Cornell engineer, he considered his days at Cornell "hard, but worth it." His studies in electrical engineering gave him a solid knowledge base in computer architecture and operating systems, and his extracurricular activities and jobs – as a technician at the student radio station WVBR and staff at ComputerLand, a local computer company – gave him hundreds of hours of experience working with and fixing equipment and systems, including early computers.

"I was involved in the very early days of personal computers," he says. "I did tech support, repair. I had practical experience. When I interviewed for jobs, people would ask me questions that would seem extremely easy. I think that was unusual for people graduating back then."

Rubinstein is only a half-time Californian these days. He spends a little over half the year in Mexico. "I'm on a couple of public company boards. I've got about 15 startups where I'm an adviser to the CEOs. I spend a lot of time on advising them on product strategy, manufacturing strategies, how to go to market, how to get distribution. It's really fun for me. I love the products and the teams building the products."

Mentors pass it along

Eva Sage-Gavin '80 says her first mentor was her mother, who helped her research colleges; together, they chose Cornell for its strong undergraduate program in a new field called human resources.

"Boy, was that research right," she says. Sage-Gavin has been a human resources executive at iconic West Coast companies including Sun Microsystems, Disney and Gap. She also is an adviser to Cornell Silicon Valley and a member of the President's Council of Cornell Women.

Eva Sage-Gavin '80. See larger image

Her time at Cornell gave her confidence and emboldened her to take risks, she realizes. She points in particular to specific skills she learned in Lee Dyer's View from the Top course, in which executives visited class to present real-world cases.

She returns to Ithaca every year as an executive-in-residence at the ILR School and teaches the View From the Top class. She also mentors students during informal group sessions and has a few long-term, formal mentoring relationships, too.

"I got some of the best training in the world here," Sage-Gavin said during her residence this April.

Arriving at Gap in March 2003, Sage-Gavin stayed on through difficult times and three company presidents, taking the opportunity to "re-invent" the clothing brand. In 2010, when her Gap position led her to the White House in support of the Skills for America's Future initiative, she turned to then-ILR Dean Harry Katz. He advised her that she had a unique opportunity, thanks to her position and values, to lead beyond her own company to improve the overall workforce. She accepted his challenge, leading Gap to roll out a new pilot program, Gap for Community Colleges, offering students strategic job and career-building skills.

"Harry's advice has been inspirational for me," she says. In April 2015, she was invited back to the White House, now as vice chairman of the Skills for America Taskforce, for an UpSkill America summit. More than 100 employers (who employ more than 5 million workers) made commitments to empower front-line workers across their businesses.

Sage-Gavin's Cornell mentors taught her to take risks. "If you're not on the edge of terror each day," she sometimes says, half jokingly, "you're not growing."

Thousands of alumni and friends serve in advisory roles, from official posts on advisory councils to unofficial but crucial service that can take the form of a phone call to a dean, a lecture on real-world experience to a classroom full of undergraduate students, or strategic introductions.

A foot in an opening door

There's a tradition in Seattle of fostering innovation and entrepreneurship that Bill McAleer '73, MBA '75, and his wife, Colleen McAleer '74, think stems from the Klondike Gold Rush. This spirit welcomed and nurtured the tech industry in its first years. Bill McAleer was there 27 years ago with executive positions at Aldus (the developer of PageMaker) and then Adobe. He subsequently started his own firm working with early stage entrepreneurs.

Today, he is managing director of Voyager Capital, a venture fund he co-founded in 1997 that invests in digital media, digital marketing and software. Adding to its presence in Seattle, the fund also has offices in Portland, Oregon and in California's Silicon Valley. "We see the whole tech ecosystem," he says, from early stage development to product prototypes.

Change.org, the San Francisco startup where Jennifer Dulski '93, MBA '99, left, is president and COO, hosted a large petition (started by Cornellians) that helped Cornell secure the bid for the Cornell Tech campus in New York City. 'I feel very connected to Cornell, even from the West Coast,' says Dulski, a Cornell Silicon Valley adviser. The leadership lessons she learned as a coxswain for Cornell crew, she says, are still relevant for everything she does as a leader today and appear in an article she wrote for Fortune Magazine in April (see fortune.com/2015/04/02/change-org-coo-5- leadership-lessons-from-my-days-as-a-coxswain/). See larger image

McAleer, a university trustee, has been instrumental in bringing CEN events to Seattle and featuring Seattle-based speakers, providing Cornellians a format for the idea-sharing and networking he found so inspiring in his early days there. He and his wife also donated to the new Cornell Tech campus in New York City, which McAleer considers a momentous opportunity. The couple supports the School of Hotel Administration, the College of Human Ecology, Entrepreneurship at Cornell and scholarship, as well.

Their cross-country drive from Ithaca to Seattle in a VW Dasher wagon 40 years ago has multiplied into many opportunities for Seattle entrepreneurs and for current and future Cornell students.

Driving on Mars

Nagin Cox '86 works as a spacecraft operations engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. In this position – a dream job for her – she drives the Curiosity rover on Mars (remotely, of course), positioning the craft so scientists can observe the planet. Her favorite part of the job is coming in every morning to a new set of images from Mars.

As an undergraduate, she pursued two degrees in engineering and psychology. "No one questioned that someone could have diverse interests," she says, noting that she still uses both disciplines daily.

The blend of excellence and breadth drew Cox to study engineering and psychology at Cornell. She shared her experience by hosting "The Big Idea! Cornell Celebrates 150" in March at the Wilshire Ebell Theater in Los Angeles. As a teenager growing up in Kansas, she told an audience of alumni, parents and friends that she knew she wanted to work at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Cornell became the clear path: "I didn't want to go to Harvard. I didn't want to go to MIT," she said. "I wanted to go to both."

She is proud of the deep connections between Cornell and JPL, which also include the 2004 Spirit and Opportunity Mars rover projects spearheaded by astronomy professor Steve Squyres.

Pursuing her intellectual curiosity

Jill Tarter '65, an astronomer who helped pioneer the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI), acquired at Cornell the engineering background she needed to pursue her intellectual curiosity. The "extremely good problem-solving skills" she honed at the College of Engineering led her to the "very interesting problems" posed in graduate Cornell astronomy courses, in particular professor Ed Salpeter's star formation class.

Jill Tarter '65. See larger image

A few years later, at the University of California, Berkeley, where she earned a doctorate, she programed the PDP-8/S computer to make astronomical observations and worked with Stuart Bowyer of the University of California and other scientists on the search for intelligent life beyond Earth.

The SETI Institute in Mountain View, California, uses the Allen Telescope Array 12 hours every day, observing 4,000 exoplanetary systems through more than 9 billion frequency channels, looking for engineered signals.

"It's not a quick process," says Tarter, who retired from daily observations as the Bernard M. Oliver Chair for SETI Research. "For the first time, we've had tools to use experimentally rather than theory," she says.

After she spoke at a Cornell alumni event, two young Cornell engineering alumni approached her – and soon became supporters. One of them, Dane Glasgow, who studied at Cornell before leaving to lead Jump Networks, a company he founded in Ithaca, is now the chairman of the board of trustees at the SETI Institute.

That special ingredient

John Wilkinson '79 supports Cornell student interns at his Napa Valley winery, Bin to Bottle. "We've had two students come every January for the last five years," he says. "We've also had summer interns and interns who worked from June to December. It's a fun program, and we stuff as much into it as possible."

John Wilkinson '79. See larger image

The student interns blog about their experiences at blogs.cornell.edu/vien-interns/.

In April, Wilkinson traveled to Ithaca to teach two sections of professor Kathleen Arnink's Wines and Vines course. Leading about 100 students through a tasting of the components that go into a red blend called Sexual Chocolate made by his Slo Down Wines brand, Wilkinson pointed out one subtle but essential ingredient that perfects the blend: port.

"It's the fairy dust in this wine," he said to the class. "In Napa, adding port is frowned upon, but we don't care."

Neither do wine consumers, apparently: Sexual Chocolate is becoming a bestseller for the brand.

Priceless confidence

As an executive at Columbia Pictures and Sony Pictures, and as chair of Viacom Entertainment Group, Jon Dolgen '66 earned a reputation as a daunting negotiator in Hollywood.

He earned his Cornell degree from the ILR School, where Dolgen Hall is named in honor of his and wife Susan's financial support for the school, but he says the most valuable skill he took away from Cornell was confidence.

"When I started," he says, "I thought everyone was first in his class except me and my roommate. When I graduated, I felt that I could go toe to toe with anyone in college.

"I learned that everything is possible. I could do anything." The confidence he gained, he said, is "a gift Cornell gave me, a gift I am still repaying."

Introducing a new president

Jim and Becky Morgan, both Class of 1960, met during their freshman year at Cornell at a student government meeting. "Women couldn't be president," Jim explains, "so Becky was vice president. I was a dorm rep."

Becky became a member of the board of trustees in 1998, served two terms, and was named a trustee emeritus in 2006. The couple has been thoughtful in their philanthropy, priding themselves on seeding projects that make a big impact over time. Most recently, they have supported the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future and established several Sesquicentennial Faculty Fellowships (see story, page 28). Their son graduated from Cornell, and their grandson will be a freshman in the fall and plans to study environmental science and sustainability.

"I can't tell you how thrilled I am," Becky Morgan says, "to have the first female president of Cornell." The Morgans hosted a reception in their Los Altos Hills, California, home this past March to introduce Cornellians to President-elect Elizabeth Garrett, who takes the university's helm July 1.

A small party of gathered alumni and friends enjoyed the magnificent view of the valley under a full moon from the Morgans' back garden, reminisced and then listened to Garrett speak. They had the chance to ask her questions and engaged her in conversation.

"People were thrilled to meet her," Becky Morgan says, "and were impressed by her energy and intelligence."

A winding path that ends up right back at Cornell

Carl Bass '83. See larger image

Last fall, Cornell announced that it had received the largest gift-in-kind in its history: software for 3-D design, engineering and entertainment valued at $51.4 million, from Autodesk, a multinational software company headquartered in San Rafael, California.

"That was an important gift for us," says Autodesk president and CEO Carl Bass '83, "and part of Autodesk's broader effort to democratize our design tools. We think it's important that professional tools are available to students and institutions, so that designers and engineers can embark on their professional careers with the skills that they will need when they graduate. Since we made that donation to Cornell, Autodesk has made all of our professional tools available to students, teachers and institutions worldwide. It's one of the things I'm most proud of at Autodesk."

Bass, a math major at Cornell in the College of Arts and Sciences, started his first company, Flying Moose Systems (later called Ithaca Software), with some Cornell friends a few months after graduating.

"We met in a lab set up by Professor [Donald] Greenberg," Bass says, "and we made graphics software for engineering and entertainment." Today, Bass employs dozens of Cornellians at Autodesk. "Brian Mathews '89 and Jeff Kowalski '88 worked at Ithaca Software and are key members of the leadership team," Bass reports.

Bass' son Jake Bass '18 is a current Cornell student. "It's great that we're sharing the Cornell experience, and also a little bit weird," Bass says. "He's taking a lot of the classes I did and has some of the same professors. ... Just this morning I got a text from him saying that he just aced his CS prelim and didn't have to take his final. It threw me back 35 years."

Someone wearing a Cornell jacket strolls on a West Coast beach. See larger image

Recognizing a frontier when you see it

California native Erik Kronstadt '06 returned to the West Coast after graduation to find that the sense of "endless possibility" instilled in him by his professors matches perfectly the spirit of freedom and new frontier he's always recognized in the west.

"I love Los Angeles," he says. "It's a place people come to live out their dreams and fantasies. That's how I felt in Ithaca."

Kronstadt is now a case team leader with the consulting firm Wilson Perumal & Co. He and others in his Cornell network – he's a board member of the Cornell Club of Los Angeles – look forward to even stronger connections between Cornell and the West Coast in the future. "People in California are really excited that there's another Californian taking office," he says of incoming president Garrett, who was provost at the University of Southern California.

Moreover, he says, the Cornell Tech campus in New York City taps into the entrepreneurial spirit and knowledge that's been present on the West Coast for decades; education is a two-way road between east and west, and Cornell is at the forefront.

"My four years in Ithaca were transformative," he says. "My Cornell connections still channel that energy."

Education is portable. That's one of the most powerful aspects of education, in fact – it travels with you. When you add to that a large, gung-ho network of fellow travelers, fellow Cornellians, the effect is magnified.

This spring, Cornellians voted to the university's board Stephanie Fox '89 (who lives in Chicago) and Jon Poe '82 (San Jose, California) as alumni-elected trustees. Poe, who is a sales manager at Cisco Systems, thinks that Cornell is and should be pursuing on the West Coast "the same goals we have globally – to create pockets of high performance to engage and lead the regions."