CORNELL HISTORY

Endowed chairs: A meeting of minds and means

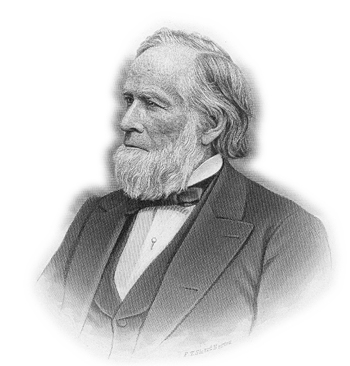

Henry W. Sage (ca. 1870), who named Cornell's first endowed chair after his wife, Susan E. Linn Sage. Photo: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. See larger image

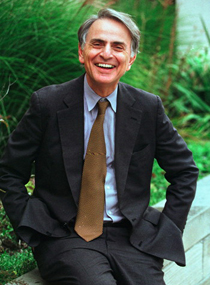

In 1968, the year U.S. astronauts first orbited the moon and one year before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took "one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind," Carl Sagan packed his bags at Harvard to become Cornell's first David Duncan Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences. Sagan went on to push the boundaries of space knowledge and single-handedly fueled popular interest in the origins and nature of our universe.

After Sagan's death, astronomer Yervant Terzian assumed the Duncan professorship and became known for his studies of exploding stars and discovery of regions of hydrogen gas between distant galaxies. When Terzian retired, astronomer Jonathan Lunine became Cornell's newest Duncan professor. Among his endeavors, Lunine is helping to design a new mission to land on Titan, the largest moon of Saturn, to explore Great-Lake-sized liquid methane seas.

Nothing would have made oil industrialist and philanthropist Floyd Newman, Class of 1912, more proud than to know that such distinguished astronomers have held the Duncan professorship that he established, and that they have had the resources to stay on the front lines of exploring the universe.

Carl Sagan, Cornell's first David Duncan Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences. Photo: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. See larger image

Yervant Terzian, previous Duncan professor, Jonathan Lunine, the current Duncan professor

Endowed chairs provide continuity. They date to 176 A.D., when Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius created four chairs in philosophy. When academics and philanthropists join forces, they accelerate creation of knowledge and respond to society's pressing needs.

Quite often, endowed professorships reflect the passions and the times of their donors. Lumber baron and trustee Henry W. Sage named Cornell's first endowed chair, the Susan E. Linn Sage Professorship of Christian Ethics and Mental Philosophy, after his wife. Sage saw religious and moral philosophy as essential to undergraduate education and believed "increase of knowledge addressed solely to the intellect does not produce fully rounded men." When he met with Jacob Gould Schurman about the open position in 1886, he was pleased to discover that the professor's "habits of teaching and thinking are quite in harmony with the desires I entertain in founding the chair … and that there is abundant evidence that all his teachings are from a distinctively Christian point of view." When he assumed the Sage chair, Schurman, later Cornell's third president, received a $3,000 salary and free rent.

Mary Donlon Alger, LLB '20, pictured in 1966 when she became a Cornell trustee emerita. Photo: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.

Historian Mary Beth Norton, who holds the Mary Donlon Alger professorship today. See larger image

The field of "mental philosophy" transitioned into the new science of psychology at the turn of the 19th century. But Sage's vision of a university that educates students to examine moral and ethical issues endures. Sage chairs today are held by Richard Boyd and Nicholas Sturgeon; emeriti Sage professors include Terence Irwin and Sydney Shoemaker. Their work has trained generations of students in moral and ethical analysis.

Throughout the 20th century, chairs were established in fields from architecture to economics to engineering, sometimes closely bridging resources with problem solving. In 1940, farmer H. Edward Babcock was alarmed that average farmers fed their chickens, pigs and cattle better than themselves and their own children. To combat the poor nutrition he witnessed across upstate New York, he dreamed of creating an ideal human diet to "see schoolchildren fed as well as cattle." Babcock established the first school of human nutrition in the world, today known as Cornell's Division of Nutritional Sciences, and created a professorship to work on interrelationships between agriculture, nutrition and health.

Babcock chair holders have included Herrell Degraff, who was recognized for original contributions to food economics, and Erik Thorbecke, who helped develop a measurement of poverty and malnutrition still in use by the World Bank and United Nations agencies. Today, the Babcock chair is held by Per Pinstrup-Andersen, 2001 World Food Prize winner and author of "Food Policy for Developing Countries: The Role of Government in Global, National and Local Food Systems."

Mary Donlon Alger, LLB '20, a federal judge, lawyer and Cornell trustee, created a professorship in the College of Arts and Sciences to be filled by women. Alger achieved many "firsts" for women at Cornell as a law school student and as an alumna. In "Women at Cornell: The Myth of Equal Education," Charlotte Williams Conable said of Alger: "Her credo that every successful woman should provide 'a strong pair of shoulders' on which other women could climb was expressed through her personal example, her active encouragement of other women, and her constant campaigns on behalf of the women of Cornell."

At Cornell, engineers and industrialists worked with new metals and machinery to advance the study of materials and technologies. Post-World War II policymakers and ambassadors studied politics and governance. Wine enthusiasts opened new doors to American vintners. Artists and humanists invested in the future of the liberal and fine arts.

The linguist Eleanor Harz Jorden, who founded Cornell's renowned Full-Year Asian Language Program (FALCON), was the Mary Donlon Alger Professor of Linguistics 1974-87. Historian Mary Beth Norton, a leading scholar of gender in early America, holds the Mary Donlon Alger chair today.

There are about 300 endowed professorships at the university; most were established during the past 50 years. Carl Sagan once said: "Presentation to the university of a chair such as mine represents a personal commitment by the donor to the pursuit of science." Like their forebears in ancient and modern times, endowed chairs continue to be anchored in fields of knowledge and discovery that reflect their namesakes' passions, commitments and vision of rising opportunities.

The groundbreaking of the Floyd R. Newman (Class of 1912) Laboratory of Nuclear Studies in 1947 (Newman established the Duncan professorship). Photo: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. Cornell President Jacob Gould Schurman, right, with U.S. President William H. Taft during a campus visit in 1916. Photo: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.