ARTS AND HUMANITIES

Element of the visual design for the "Unpacking the Nano" exhibit design that will be at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art Jan. 18 through March 21. See larger image

'Unpacking the Nano' explores a revolution in design and transportation

What does it take to design and mass-produce an automobile to sell for around $2,500? And what are the inevitable environmental, social, economic and cultural impacts of having 5 million, 10 million, 50 million such cars (and first-time car owners) on the road?

The College of Architecture, Art and Planning (AAP) will explore these and other questions related to Tata Motors' revolutionary new Tata Nano in an exhibition at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art.

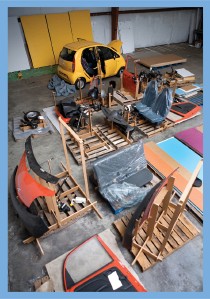

"Unpacking the Nano," on display Jan. 18 through March 21, 2011, will feature two production Nanos – one of them taken apart to highlight 16 critical subassemblies, with parts suspended by wires in the gallery – and the original concept vehicle.

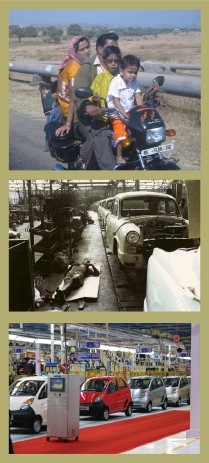

Top: The Nano could be a safer alternative to two-wheeled transport in India. Center and bottom: Then and now: A worker sleeps beside the assembly line for Ambassador automobiles in 1960s India; Nanos roll off the line in a new Tata Motors factory. See larger image

The exhibition team of AAP students, faculty and young alumni has created custom shipping crates for the Nano's parts and subassemblies. Each crate side doubles as an exhibition panel, with text, maps, charts and other graphics showing cost, weight and other statistics.

"The question we asked [in organizing the exhibition] was, 'What do all the nuts and bolts add up to?'" says project co-director Alex Mergold, B.Arch. '98, a visiting assistant professor of architecture. "What does the Nano add up to as a car, a piece of engineering and design, a status symbol, a social construct, a financial asset, an environmental hazard, a solution to India's mobility problem? This thing brings out many debates, and that's what we are hoping to stimulate."

Much like Henry Ford's Model T did in North America a century ago, the Nano is poised to bring about widespread change across the Indian subcontinent and globally. The company ultimately wants to produce as many as 2 million cars a year.

Production of the Nano in India began in 2009; about 250,000 Nanos will ship in 2010 alone. Designed by a team of 70 Tata Motors engineers, the four-door car seats five, has an aluminum two-cylinder engine, weighs 600 kilograms, and gets up to 65 miles per gallon of gas.

"The design accomplishment is truly extraordinary," says Kent Kleinman, the Gale and Ira Drukier Dean of AAP, who discussed the car with Tata Group chairman Ratan Tata '59, B.Arch. '62, during Reunion 2009, and later led an AAP delegation that toured the factory in India.

The exhibition highlights "the role of design as an agent of profound social change," Kleinman says. "We're lucky to have privileged access to such an innovation of epic dimensions."

Ratan Tata '59, B.Arch. '62 and AAP Dean Kent Kleinman discuss the Nano in 2009 on campus. See larger image

The display also addresses safety and the car's role in sustainability in India and other industrialized nations, and casts a critical eye toward American automotive culture.

A related symposium, "Unpacking the Nano: The Price of the World's Most Affordable Car," will be held in March.

The Nano raises specific issues for architects and planners, since expanding transportation on a large scale could cause a "suburbanization of the global south," Kleinman says.

Tata engineers worked to meet a price of one lakh (100,000 rupees, or around $2,200 in 2009 U.S. dollars), a symbolic price benchmark in India.

"It was started from a blank slate," says exhibition team member Spencer Lapp, B.Arch. '09. "[Tata Motors] started with the idea that this car was going to be much less than it eventually became. They tried a design with no doors, plastic curtains and a plastic body. They discovered they could design a car that people would want to drive, not a golf cart."

Spencer Lapp, B.Arch. '09, Sarah Haubner, M.Arch. II '10, and Ben Widger, M.Arch. '11, work on color-coded Nano exhibition panels in The Foundry. See larger image

Ratan Tata's goal was to bring motoring to the masses in India, where highway infrastructure is improving and the middle class is growing. The Nano was designed as a safe, affordable alternative to the millions of two-wheeled vehicles, motorized and not, now on the road.

Using parts and assemblies from outside manufacturers proved ineffective, so Tata engineers provided "in-house innovation," designing parts themselves. Lapp says: "The value engineering became a very effective strategy; the car's weight essentially drove the cost, and they got it down to 2,000 parts." A typical car on the road today has about 3,500 parts.

"It's a balance between what they were going to get rid of versus what they needed to keep," says Ben Widger, M.Arch. '11. "It was going to be a two-door car before they realized that women in saris couldn't get into the back seat."

A complete Nano and a car in pieces will be featured in "Unpacking the Nano." See larger image

The project has opened up "huge" teaching possibilities, Mergold says. "During the research phase we ended up with mini-courses on design, engineering, environment, anthropology, sociology – all during only one semester."

"For our college it's always a question of defining a problem, and then synthesizing a solution," Mergold says. "In our case the problem was finding the way to present many conflicting arguments as well as a wealth of technical information about the car – in an art museum. And then we had to go above and beyond … into implementation. For the students that alone was an invaluable lesson, to see their ideas become material and understanding what that actually takes."

For more information, go to aap.cornell.edu/events/nano.