COVER STORY

Q&A: Reports from the front line of ideas for a sustainable planet

Cornell's faculty works at the epicenter of a global effort to understand and ultimately provide workable solutions to urgent environmental, ecological and energy challenges to the planet. Ezra posed some provocative questions to a few of the more than 300 professors working on sustainability projects in the Colleges of Engineering; Agriculture and Life Sciences; Arts and Sciences; and Architecture, Art and Planning; and at the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future, founded by David Atkinson '60 and his wife, Patricia.

Natalie Mahowald, investigator of climate dynamics and humans' impact on the environment. See larger image

Is climate change really happening?

Yes, we can see the changes in climate in surface temperature trends, here in New York and across the globe, especially in the Arctic. Ship-borne observations of temperature show the oceans are warming. Satellites have detected the higher sea levels that are a result. Snow in the spring in New York and across the United States and Europe is gone earlier. Sea ice in the Arctic is reduced during the summer to the point where, for the first time, commercial ships can now navigate the Northwest Passage connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. All this provides evidence that climate change is indeed happening.

– Natalie Mahowald, associate professor, earth and atmospheric sciences, and lead author, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

David Wolfe, who studies bloom and leaf trends. See larger image

It's not just the thermometers telling us the climate is changing; the living world is already responding. As the planet warms, the range of many species is shifting northward, and in the spring plants are blooming earlier. Apples, lilacs and grapes are blooming four to eight days earlier than in the 1960s. Migrating birds and insects are also arriving sooner than expected. Those who make their living from the land will be on the front lines of confronting this challenge.

– David W. Wolfe, professor, horticulture, and chair, Atkinson Center Climate Change Focus Group

What's the single biggest obstacle between us and a sustainable energy future?

Jeff Tester '66, M.S. '67, thinks that geothermal energy has the potential become a major source of U.S. electrical power. See larger image

Eventually, we need to transition completely from relying on finite fossil fuels to using renewable resources. This transition requires that we develop and deploy renewable resources at an enormous scale, but also we need to be much more efficient in the ways we use energy. Cornell is unique in organizing efforts in a larger sustainability context, focusing on connectivity in three general areas – energy, environment and economic development – because we can't solve the energy challenge without looking at the big picture. We have enormous capacity within our 11 endowed and land-grant colleges and the strong commitment of our students, faculty and staff – from the newest freshman to our president. Combining this vision with the passion of Cornell's alumni, as evidenced by the enormous generosity of David Atkinson and David Croll, is what attracted me to come back home to Ithaca. Returning to Cornell to be part of this exciting opportunity has energized me beyond what I once thought possible.

– Jeff Tester '66, Croll Professor of Sustainable Energy Systems, and associate director for energy, Atkinson Center

Cornell researchers are developing viable renewable energy sources. What looks most promising to you?

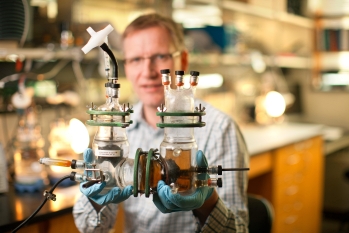

Lars Angenent, inventor of a novel anaerobic bioreactor, is developing a way to produce fuel from cow manure. See larger image

I am interested in converting organic waste materials into energy. This kills two birds with one stone, since we both need to treat wastes and generate renewable energy. In New York, we are especially poised to use organic wastes because we have two large sources – dairy manure and urban wood waste. My lab uses microbes to generate methane in anaerobic digesters and carboxylates and alcohols in fermenters. I believe strongly that our society should choose these alternative methods of generating energy before we further explore nonrenewable energy sources, such as natural gas. If we do explore natural gas, we should use the economic returns to develop a renewable energy sector in the state. In my lab, we have made breakthroughs studying the production of bio-based chemicals as a way to make conversion technologies more cost competitive with traditional energy sources.

– Lars Angenent, associate professor, biological and environmental engineering

Modern wind turbines are the largest of man-made moving objects, with spans greater than that of a Boeing 747. They also work under the most inhospitable conditions: rain, snow and ice, and above all, a highly intermittent wind field that gusts in a random way. One of the cutting-edge problems we are focusing on is the rare, high amplitude wind events that can sometimes cause a turbine's drive train to fail due to the resulting high stresses. Wind tunnel tests show that when there is wind shear and multi-scale turbulence, then rare gusts, like mini tornadoes, may occur with frequencies 1,000 times or more than would be expected using simple models. By understanding these wind events we can influence wind-turbine and wind-farm design to better withstand them.

– Zellman Warhaft, professor, mechanical and aerospace engineering.

Our work with algae is a good example. Cornell researchers from myriad departments are engaged in a range of activities: crop selection and breeding, bioprocesses, bioseparations, bioproducts and, most important, lifecycle analysis of the potential negative impacts of extensive scale-up in biofuel feedstock operations. Through an Atkinson Center grant, our research team has been exploring algal biotechnology in order to improve the viability of large-scale algal biofuels cultivation. We also have a Department of Energy-funded collaboration with Hawaii-based Cellana Inc. – one of the few existing pilot-scale production facilities for lipid-accumulating algae.

– Ruth Richardson, associate professor, civil and environmental engineering

Our recent research marks important and potentially transformative steps toward realizing the technological potential of nanomaterials in future solar cells. We have created novel nanocrystal quantum dot tandem solar cells that efficiently harvest solar energy in thin film devices processed from solution. This achievement marks the convergence of two important solar cell concepts: low-cost processing and engineering to efficiently absorb and convert the broad spectrum of solar energy. Essentially, this is a way to harvest more of the sun's power for less cost.

– Tobias Hanrath, assistant professor, chemical and biomolecular engineering

What outside the box innovations are emerging from Cornell's sustainability research?

We are working with The Conservation Fund on ways to help the red-cockaded woodpecker in North Carolina using computational sustainability to model complex conservation issues. Ecologists have long studied migration patterns for this endangered species, and so we incorporated their descriptive models into a larger context to illuminate which tracts of forestland should be kept as reserves over an 80-year time horizon to improve the woodpecker's chance of survival. Our computational models are similar to the "planning under uncertainty" process that companies like Amazon.com use to manage inventory. The next step is to look at the feasibility of moving some birds to new, artificial nests and whether that will help in the long run.

– David Shmoys, professor, operations research and information engineering

The increasing carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in the atmosphere is a big concern, and we need engineering solutions to essentially put the CO2 back in the box. Scientists everywhere are exploring ways to tie up the atmospheric CO2 so that it won't contribute to greenhouse gas warming. One alternative is to pump the CO2 deep underground and trap it in the pore spaces of rocks. We looked into the feasibility of storing CO2 at greater than 3,000 feet below central New York, but we discovered that other regions of the U.S. have much better storage potential.

– Teresa Jordan, professor, earth and atmospheric sciences

Chris Barrett has said: "I'm interested in improving the well-being of the poorest members of humankind and doing what we can in practical terms to help them help themselves." See larger image

Droughts routinely spark humanitarian crises in the dry lands of East Africa, as they have this year. Insurance to cover catastrophic livestock loss wasn't available until we figured out a way to use satellite-based measurement of rangeland vegetation to predict losses and underwrite novel index-based livestock insurance contracts in Kenya. To tailor the insurance to alleviate poverty and support development in fragile rangeland ecosystems, we first put global positioning system collars on the herds, enabling us to track any changes in herd patterns or ecological conditions.

– Chris Barrett, the Stephen B. & Janice G. Ashley Professor of Applied Economics and Management, Dyson School, and associate director for economic development, Atkinson Center

How does Cornell rate at fostering interdisciplinary collaborations?

When I arrived at Cornell, my goal was to develop a research and outreach program focused on the economics of food supply chains, emphasizing linkages to other disciplines such as nutrition, environmental sciences and engineering. We first organized a lunch at the Atkinson Center around the sustainability of food systems, then we generated an Atkinson grant proposal involving faculty from three colleges and nine departments. The first year of the grant, we met regularly to develop a common language and to identify key links among the primary multidimensional sustainability aspects associated to food systems. We also used the grant to build external partnerships with public and private organizations. As a result, today we have not one but two large multistate, multidisciplinary grants funded by the federal government.

– Miguel Gomez, associate professor, applied economics and management

Susan Christopherson, an economic geographer, has conducted comprehensive impact studies of natural gas drilling.

I'm fortunate to be trained in geography, a field traditionally concerned with human-environment relations. Cornell's focus on sustainability has created many more opportunities for faculty and students interested in connecting across disciplinary boundaries to learn from one another. The scientists, social scientists and engineers who work together are unusually curious, life-long learners, and able to listen. This year we extended our interdisciplinary project to a course on energy transitions that has attracted students from engineering, natural resources, communication, as well as city and regional planning. One thing that seems to unite the faculty at Cornell working across fields is their commitment to Cornell's land-grant mission. Because we are focused outward – on the bigger goal of serving the community – we find ways to work together.

– Susan Christopherson, professor, city and regional planning

Rod Howe leads Cornell efforts to improve New York state's environmental health, education and access to sustainability science. See larger image

What impact is Cornell sustainability research having close to home, in upstate New York?

At Cornell Cooperative Extension, our educational approach to energy solutions takes into account the protection of environmental health, creating and maintaining vital communities, and promoting economic opportunities. For instance, we have responded to a wide variety of stakeholders who seek a scientific, economic, social and environmental understanding of the issues associated with Marcellus Shale natural gas exploration and drilling. This has been a tremendous example of a land-grant university at work. I now hear citizens and policymakers using such concepts as energy transitions, which is based on the need to move toward renewable energy sources and using a "systems approach," which looks at all levels of impacts, including social, economic and environmental, thanks in part to CCE's effort to raise what we call "energy literacy." We want to empower people with knowledge to make their own choices about energy development.

– Rod Howe, assistant director of Cornell Cooperative Extension

What will our grandchildren's lives look like?

Drew Harvell, coral reef expert. See larger image

As a scientist who studies oceans, you might expect me to say that we will leave a world to our grandchildren with terribly reduced ecosystem services, no coral reefs, coastal areas inundated from sea level rise, and a massive exodus of coastal people as climate refugees. And that is certainly a possibility. However, despite the dire outlook today, I have hope that our society will undergo a global tipping point that will alter our future behavior and result in a world for our grandchildren with sustainable oceans. Call me overly optimistic since I don't know where the solutions will come from, but I think there should be hope. First, young people are starting to stand up for their rights to inherit a sustainable world. Second, we are assembling a global effort to manage our oceans better than we ever have. And third, we are putting in place renewable energy research and plans for sustainable living that will change our lives.

– Drew Harvell, professor, ecology and evolutionary biology, and associate director for environment, Atkinson Center

Ask a historian about the future, and you're bound to get an evasion. The great lesson of historical study is that nothing is inevitable, that every event or development could have gone in a thousand different directions. Change is not only constant but also contingent, uncertain, utterly unpredictable, influenced by innumerable causal forces, by the smallest decisions of ordinary people. But I happen to be an environmental historian, so I do try to stay aware, as it were, of which way the wind is blowing. I imagine, in a few decades, that the world is going to be hotter and stormier and that we might even have to abandon some places, maybe like Miami and New Orleans. One thing I know from history is that values tend to change slowly. But there are examples of ideological revolutions: very few Englishmen living in 1770 would have predicted that their grandchildren would abolish slavery throughout the Empire. Maybe our grandchildren will abolish pollution.

– Aaron Sachs, associate professor, history