BIG RED ATHLETICS

Remembering legendary Big Red coach Ned Harkness

In an old horse barn, a chilly hockey rink and a hard grass field, Nevin D. "Ned" Harkness taught life lessons to hundreds of young men in Ithaca. He was their mentor, who took all the knowledge on a subject and gave it practical applications. Harkness could relate to and motivate them all.

He was the face of the madness that still to this day prompts students to wait in line all night for the right to purchase ice hockey tickets, to stand and yell at Harvard. He turned around the fortunes of a lacrosse program that hadn't posted a winning record in five seasons, helping the team to its first two Ivy League crowns and a 35-1 record in his three years directing the program.

Ned Harkness waves to the crowd following the dedication of the Ned Harkness Alumni Room at Lynah Rink on Oct. 13, 2007, with former players Murray Deathe 67, left, and Ken Dryden 69.

Harkness was the Renaissance man who led the Big Red through a golden era of athletics. An innovator in lacrosse and ice hockey who brought out the best in so many young men, Harkness became a legend at three different colleges.

When he took over the Cornell hockey team in 1963, the Big Red had just two winning seasons in the previous 24 years. His first team went 12-10-1, finishing one game off a school record. The next year, that record jumped to 19-7, then to 22-5 in 1965.

"We wanted to make Lynah Rink the place 'where angels fear to tread,'" Harkness said.

First, student crowds came to witness the winning team. The community soon followed. In his final four years on the Cornell bench, Harkness' teams enjoyed a 110-5-1 record, placing in the top three in the NCAA tournament each time. The Big Red celebrated national championships in both 1967 and 1970. By then, the rink was at capacity every night, watching the Big Red win 47-1 in home games, outscoring opponents 338-71. The last 42 times Cornell dressed at home under Harkness, it skated off the ice in victory. That streak would climb to 63 consecutive home wins under his successor, Dick Bertrand.

Harkness after the 1967 NCAA championship game, held in Syracuse. See larger image

When Harkness died Sept. 19 at age 89, so did the father of the Lynah Faithful and the mastermind behind Cornell's running streak in lacrosse.

"Don't stand around, you're killing the grass," Harkness would yell to players not in a lacrosse drill at that moment. Run anywhere. Move. Do anything. Anything but stand still and watch.

He believed that the less talented team could always win if it was in the best shape, and that his squad would be the last one standing, but only by not standing around.

While Harkness was head coach of the hockey team, tragedy befell the lacrosse program. Two assistant coaches were among four people killed in a plane crash during a 1965 recruiting trip.

"[Lacrosse coach] Bob Cullen had asked the day before if I would help with the lacrosse team," Harkness said. "I went out and said to them, 'I don't know you, and you don't know me, but you're going to run more today than you ever have in your lifetime.'"

A year later, those same players requested that Harkness be elevated to head coach after Cullen stepped down. Two Ivy League titles and a runner-up finish later, and Harkness had written his name in the lore of a second sport at Cornell.

The hallmark of a Harkness team was that it was almost without fail the last one standing. Few coaches in any sport have led teams to victories as often. His Cornell teams were triumphant 87 percent of the time. His 1969--70 hockey team remains the only unbeaten and untied group in NCAA history, posting a perfect 29-0-0 mark en route to a national title. He was also at the helm of a pair of undefeated lacrosse teams, and his 35-1 record in three campaigns as head coach is good for an unfathomable 97 percent winning percentage.

That only tells part of the story. Before Cornell, at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), Harkness turned the school lacrosse and hockey crazy. He guided the hockey team to a 176-96-7 mark with a national title in 1954 and a third-place finish the season before. His lacrosse teams were equally good, compiling a 112-26-2 mark and a USILA national championship in 1952. His 1956 club finished No. 2 in the nation. Added together, along with a short three-year stint at Union College as head hockey coach, Harkness guided teams to a 532-158-14 record as a head coach.

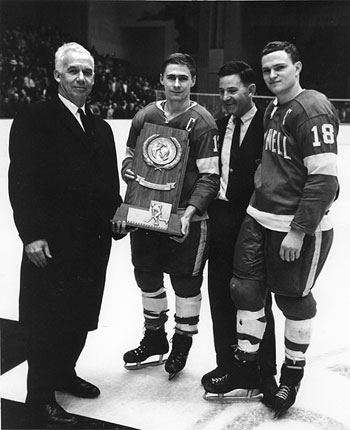

David Ferguson 67 (holding trophy), Ned Harkness and Murray Deathe accept the national championship trophy after defeating Boston University, 4-1, on March 18, 1967, in Syracuse. See larger image

While the numbers are mind-boggling, Harkness as a mentor can't be measured tangibly. His former players -- later engineers, doctors, lawyers and politicians -- were loyal to his last days. They traveled to Ithaca and Rensselaer in his final years to see him at ceremonies, called him when he lived in Florida and spoke of him with reverence at every opportunity.

"To this day, I've not met anyone like him as a man, a father figure, as a model and as a coach. …There is no greater motivator out there," said Bertrand, who was a captain of the 1970 hockey team. "He made such an impact on so many people, and he affected so many lives. No matter how many years after you left Cornell, he would still be there for you. …

"Even after a loss," Bertrand added, "he'd give us a tongue lashing, but he'd never let us leave that locker room without feeling good about ourselves. That's a God-given talent, and he was able to do it."

And he was an innovator -- many of his ideas and tactics have been studied and copied ever since.

"There was the 'Maryland Ride' that everyone was bragging about, and how no one could break it," said Tom Harkness, who played lacrosse for his father. "[The strategy was that] he gave Bobby Smith the ball with the idea that you couldn't take something from someone you couldn't catch. He had him run it right through the team."

Harkness would coach goalkeepers without sticks. With All-American Butch Hilliard, no one else was allowed to shoot on him during warm-ups. The head coach would make Hilliard use only a broom handle to teach him to move to the corner and quicken his feet.

In hockey, his use of walkie-talkies with an assistant in the press box was unique, as was his decision to recruit Canadians. Players also recount times in lacrosse when he would run a midfield or attack line of deep reserves with the full understanding that they may not score a goal, but would fight like heck to keep the opponent off the scoreboard and give an extra minute or two of rest for the starters.

Harkness was a man in constant motion, and he expected those around him to have the same energy, the same passion.

"He would adapt the strategy to his team," Tom Harkness said. "People would say you could see his mind work, figuring out things as the game would go on."

Of course you could.

Harkness never stopped. Because of that, the Cornell ice hockey and lacrosse programs have a legacy of success that span well beyond the victories and national titles.