ENDNOTE

How a design progressed from concern to challenge and collaboration

Renny Logan

Most of our work comes to us from new clients who have a special project and who have already seen and admired the character of our buildings in the United States and Europe. A visionary Cornell administration approached us with a new building for the life sciences because of its substance and meaning to Cornell's future, and because of Richard Meier's stature as perhaps Cornell's most prominent architectural alumnus today.

The commission must have been a leap of faith for the university because we had never designed a laboratory building. Laboratories are notoriously complex, and the challenge was increased substantially with the need for a flexible facility that could adapt and change to the needs of science well into the future.

Our approach to Weill Hall was different than it would have been for a museum or a church, which are more intuitive and conceptual processes with simpler programs. Indeed, Weill Hall has more in common with the two federal courthouses we have designed -- buildings with many highly organized components.

As a design challenge, however, a science building is not so different; we may not initially be familiar with the pieces, but learning about them is an objective process made easier with the help of expert advice from our design team along the way. We listen, we learn, we interpret.

Over much of the eight years it took to bring Weill Hall to fruition, the listening and learning was done by the design team that Cornell and Richard Meier & Partners assembled, consisting of architects, engineers and various specialty consultants that numbered almost 30 professional groups.

Ultimately, Weill Hall was based on the notion that large, programmatically complex buildings are best designed around simple organizational ideas. The most flexible space was assembled in a continuous lab zone occupying several floors in one wing of the building, while other unusual labs, non-labs or "dry" space (computer-related research, the business incubator and more typical office space) are in the opposite wing across the atrium. Not immediately apparent is that much of the building's program spaces that require controlled light and vibrations are concealed underground in an enormous area twice the size of the building's footprint above.

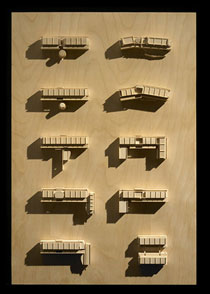

Early study models of what would become the design for Weill Hall, created during the concept design phase of the project in 2002 03. See larger image

The atrium space between the two wings is the heart of the building, and is the key component encouraging fluid interaction among building researchers and students. The large central communal space is like a piazza at the terminus of the corridor streets of each wing to encourage social and academic interaction, as well as to anchor a center, heart and living room to the communities being created at each level. We have long understood the importance of an identifiable center as an orientation point in large buildings, such as the Getty Museum, and have more recently come to understand their social significance.

During construction, Scott Emr, director of the Weill Institute in the south wing, pushed that concept of interaction one step further in asking for adjustments to the office zones at each floor to accommodate a little "neighborhood café" where each department would have a central break/lunch area and common journals library. It isn't uncommon to make adjustments to a design during construction. It is unusual and even ironic for a user to so freely embrace the social goals of the design that he's willing to give up precious programmed office space to create additional interactive areas.

In the laboratories, Emr and associate director Tony Bretscher so appreciate the quality of light, openness and flexibility in the south wing lab spaces that they have generally resisted the temptation to partition them.

It has been exceptionally gratifying for all of us to see researchers' initial skepticism and concern for maximizing research space in the building eventually give way to an appreciation for how architecture and design can enrich the quality of their lives and research. Admittedly, there were some shaky periods when we weren't always confident that researchers' expectations would be married to the university's goal of making a great campus building.

Weill Hall is the product of one of the most genuinely collaborative team efforts we've ever been part of, and it has been a rare opportunity for us as architects. Perhaps for the first time we are even more proud of our modest contribution toward embellishing the process of important research for decades to come than we are of the building we leave behind.

Renny Logan is an architect and associate partner with Richard Meier & Partners.