COVER STORY

(Page 3 of 5)For a glimpse into the future, Cornell's Department of Biomedical Engineering is one place to look.

The department, in some ways, is a "reflection of modern reality" – what engineering departments will look like 10-20 years hence, says Rick Allmendinger, professor of earth and atmospheric sciences who is the college's associate dean for diversity.

The department is peppered with junior faculty, and half of its graduate students are women. In total, 24 of its graduate students are recipients of prestigious NSF fellowships, of which several were awarded to minority students. Biomedical engineering is just one department that has had success with recruiting female graduate students; for example, chemical engineering has also had 50 percent women Ph.D. students in recent years.

Sara Xayarath Hernandez, director of Diversity Programs in Engineering. See larger image

There are, of course, many factors that help biomedical engineering achieve these demographics, says Peter Doerschuk, the department's director of graduate studies. Compared with fields like physics and math, biomedical engineering is relatively new. Though active in the discipline for 50 years, Cornell only established a department in 2004.

"The interdisciplinary nature is attractive, with the idea of contributing to human welfare, and I think the novelty is attractive, too," Doerschuk surmises. "It is the youngest discipline in the college … We have a much richer diversity situation."

However, when it comes to women faculty, biomedical engineering as a discipline is still a leaky pipeline. According to a 2010 study in Annals of Biomedical Engineering (Vol. 38 No. 5), although the percentage of women in biomedical engineering is higher than many other technical fields, and despite a relatively rich pool of Ph.D. candidates, it is far from being in proportion to the U.S. population.

To seek a balance, faculty members Cynthia Reinhart-King and Claudia Fishbach-Teschl, both assistant professors in biomedical engineering, have started a graduate student women's group in the department. Reinhart-King remembers the first meeting; half of the women were excited, and the other half skeptical. Gender has nothing to do with the fact that we're scientists, they said.

But as a full-time faculty member who is also balancing a family life, Reinhart-King believes in the importance of such groups.

"There are plenty of studies that show that just knowing you are not alone and that you have role models is valuable," she says. "There are definitely concerns at the graduate level, when women are thinking about what kind of job they are going to take, and what will be the effects on their personal life." (See sidebar, page 11.) Other departments, such as materials science and chemical engineering, also have active graduate women's groups.

Diversity as a policy goal

Aggressive recruitment and retention strategies are making their way into college policy. Allmendinger, who oversees the Diversity Programs in Engineering (DPE) office, also is responsible for monitoring all tenure and promotion cases across the college. Throughout the process of recruiting new faculty, he notes, diversity is a unifying and overarching goal – of particular importance as the college hires the next generation of faculty through the universitywide $100 million Faculty Renewal Fund (see related story, page 22).

He is in a position to help junior faculty make the transition to success – for example, making sure they don't become overcommitted, as assistant professors so often do. "I can tell them the most important thing they can do for diversity is to get tenure," Allmendinger says.

He also chairs the college's Strategic Oversight Committee, created in 2007 to monitor the hiring process and keep search committees accountable to good recruiting practices that pay attention to diversity. According to Collins, just having an associate dean for diversity underscores the importance of the issue.

"It gives that person leverage – and that is required – to oversee the searches going on across the whole college," Collins says.

Gone are the days of traditional faculty searches, where a bunch of journal ads sufficed, and "you waited to see who came in," Collins says. "That is a very unlikely way to yield a rich pool of diverse candidates."

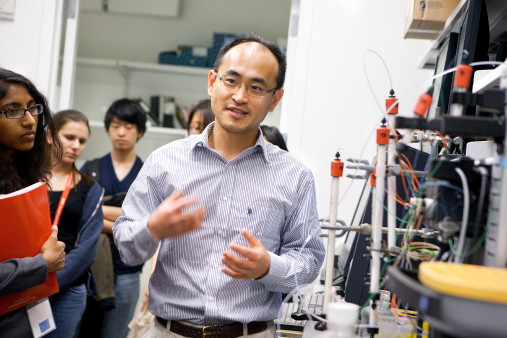

Moonsoo Jin, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, leads a lab tour for prospective engineering students on manipulating molecules and nanotechnology for better detection of cancer.

Instead, Collins says, search committees are expected to consider the word "search" in its truest sense. "They should be using their networks to find candidates out there who are outstanding, maybe at their earliest stages of development, who are not even sure they want an academic career," Collins explains. "They are not the ones who are necessarily going to immediately submit their resumes, but they are qualified potential faculty. We want an active process."

<<View entire story as one page>>