PEOPLE

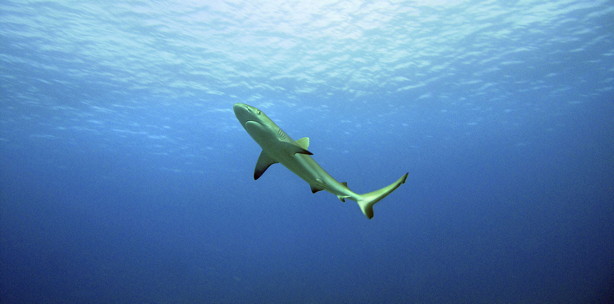

A whitetip reef shark near Enderbury Island, part of the Canton and Enderbury Islands in the Pacific Ocean.

Two alumni under the sea

Coral reefs thrive in crystal-clear waters, kept so partly by these plankton-eating fishes. See larger image

Imagine having a career that allows you to scuba dive in coral reefs around the world. Or what if you were a veterinarian who heals seals wounded by fishing nets and sea turtles injured by passing boats? For two Cornellians who work for the New England Aquarium in Boston, such adventures are a part of the job.

On March 11, 2011, the day a tsunami devastated Japan's northern coast, Randi Rotjan '99 (neurobiology and behavior), an associate scientist at the New England Aquarium who works to conserve coral reefs around the world, was on a boat researching the health and ecology of a coral reef in Indonesia's Raja Ampat Archipelago.

She checked her satellite phone and learned the tsunami was about to pass their way. Rotjan and her colleagues had no time to leave the area; the tsunami passed under the water's surface, raising their boat by only an inch. "Had the boat been raised by a foot or more, we would have been caught on the reef and wrecked," Rotjan said. "We were very lucky."

Randi Rotjan '99 under the sea during an expedition. See larger image

Before she had a baby this year, Rotjan, who received her Ph.D. in biology from Tufts University, spent four to six months a year in the field in such places as the Red Sea, Indonesia, Panama, Belize and the Central Pacific's Phoenix Islands, one of the most remote areas on the planet, and the location where Amelia Earhart's plane is thought to have crashed.

"The Phoenix Islands allow us to decouple the local versus global human issues," Rotjan said. "It's a great place to calibrate what's going on, on a climate-change level, without having to worry about the local pollution [and other] more immediate human threats." In such surroundings, Rotjan loses track of time, lives at the whims of the sea and weather, and becomes deeply focused on her work. While diving, she has seen wrecked ships, manta rays, huge parrotfish, mating turtles, hundreds of sharks, and areas where coral covers almost 100 percent of the ocean floor.

Though Rotjan will increase the time she spends in the field again as her daughter gets older, when she is in Boston, roughly 15 percent of Rotjan's job is to write and ensure accuracy of exhibit panels pertaining to her expertise as a "coral doctor." She also runs a research lab with graduate students, interns and postdoctoral researchers, and teaches college classes.

Coral reef scientist Randi Rotjan '99 at sea (her recent expeditions include trips to the Central Pacific Phoenix Islands, Belize, Indonesia and the Red Sea). All images provided by the New England Aquarium. See larger image

Through her lab, Rotjan studies predation on coral by such animals as parrot and puffer fishes. She also monitors marine protected areas like the Phoenix Islands and studies a tiny New England coral, Astrangia poculata , that has photosynthetic properties.

Coral around the world is changing for different reasons in different places, Rotjan said, with almost all the damage due to human pollution, disease, overfishing and sedimentation, and such global human impacts as warming waters and ocean acidification.

Charles Innis '90 (biology), who earned a doctorate in veterinary medicine from the University of Pennsylvania, cares for some 850 species of marine animals at the Boston-area aquarium, where he also contributes to exhibit design. Part of his clinical work is with turtles, small dolphins, porpoises and seals brought in for rehabilitation or in the field, in such places as the Gulf of Mexico after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Innis applies information from working with free-ranging animals to care for captive ones and determine if they are sick.

Veterinarian Charles Innis '90 (second from right) poses with a research team that briefly live-captured giant leatherback turtles to learn more about the physiology of this endangered species near Cape Cod in 2009. See larger image

In late September, Innis and colleagues helped rehabilitate a 7-foot-long, 655-pound leatherback turtle found near death on Cape Cod. The turtle was given medications and nutrients, outfitted with a satellite tag and released within 48 hours. Three weeks later the turtle was detected heading toward Bermuda and diving down to 240 feet. The treatment and release marks only the third successful leatherback rehabilitation anywhere.

Innis and his colleagues learned from the two previous successful rehabilitations that leatherbacks, the world's largest sea turtle (they can grow to more than 1,000 pounds), do not live long in captivity, Innis said. "The key is to treat them quickly and get them back in the ocean," he said.

Veterinarian Charles Innis '90 checks on a juvenile Kemp's Ridley sea turtle (the world's most endangered) before an MRI. See larger image

Though Innis has treated everything from penguins to fish and seals, turtles are his main area of interest. "I've been interested in them for as long as I can remember," he said, adding that they are an evolutionary marvel, having lasted some 250 million years with the same body form. Still, freshwater, terrestrial and marine turtles are all in trouble, mainly due to human activities: They get hit by cars and boats and encounter development in prime nesting areas. "There are a lot of turtle species around the world that are monitored by conservation organizations that are trying to prevent them from becoming extinct," he said.

Both Innis and Rotjan remember their time at Cornell fondly.

A healthy stand of Caribbean elkhorn coral provides shelter for fishes and other reef organisms. See larger image

"I miss Ithaca badly; I dream about it a lot. I really miss the environment up there," Innis said. And Rotjan, who began college with aspirations of becoming a writer, credits a supportive atmosphere at Cornell, her neurobiology and behavior professor and honeybee expert Thomas Seeley, and a summer course at Shoals Marine Lab for her switch to science.

"It was thanks to the general liberal arts education at Cornell, really excellent teachers, having access to Shoals Marine Lab, and Tom Seeley, who set an amazing example of what science can and should be," she said.

The New England Aquarium, www.neaq.org, is located on Boston's downtown waterfront and features more than 50 exhibits, thousands of marine animals and an IMAX theater. It also is a pioneer in marine animal rescue and a leading ocean conservation organization, with research scientists working around the world.