COVER STORY

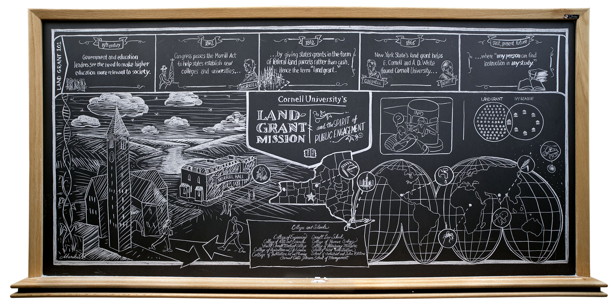

The centerpiece of a new video, "Cornell's Land-Grant Mission and the Spirit of Public Engagement," is the on-camera creation of this large chalkboard mural by Ithaca artist Marshall Hopkins. The drawing and the video chart Cornell's historic land-grant founding and how that mission has evolved into the university's global engagement today. The video, available at www.cornell.edu/video/?videoID=2432, was produced and directed by Cornell video producer Micah Cormier and debuted during Trustee-Council Weekend in October in Ithaca.

Action Teens, apples and the spirit of democracy: Cornell's culture of public engagement expands the definition of 'land grant'

What President David Skorton has called Cornell's "commitment to developing knowledge that benefits communities" is closely tied to the university's land-grant mission. See larger image

In April, CARE, one of the world's largest humanitarian organizations – with field offices in 84 countries and an annual budget of more than $500 million – announced a unique partnership with Cornell that has the potential to maximize the impact of both institutions' work on gender, food security and poverty.

Cornell President David Skorton heralded the partnership as "an important milestone in bringing the impacts of research to our human family."

The collaboration is also a modern example of what has long been known as the university's land-grant mission to translate knowledge into solutions for real people and real communities, and to engage with, and respond to, the challenges of the real world.

Erin Lentz, third from left, a research support specialist with Cornell's Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, with villagers in Kargi, Kenya, who she interviewed as part of a 2008 project to assess which form of food assistance they preferred. She and other Dyson School researchers developed a tool to help international relief organizations cater their food aid response to specific situations. Photo: Andrew Mude. See larger image

For many people, the term "land grant" conjures up only images of the university's engagement with agriculture – apple orchards, cows, dairy farms and Cooperative Extension offices providing composting classes for gardeners. Indeed, many people are under the mistaken impression that only Cornell's state-supported colleges (the Colleges of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Veterinary Medicine, Human Ecology and the ILR School) are "land grant" schools.

"In fact, that's not true," points out Robert Harrison, chairman of the Cornell Board of Trustees and CEO of the Clinton Global Initiative. "Every department, every discipline, area, major and college [at Cornell] has the same obligation and same public-service mission."

Cornell is New York state's land-grant university. The U.S. Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862 provided a grant of federal land to each state to provide for "at least one college in each state where the leading object shall be, without excluding other scientific or classical studies, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts [engineering] ... in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes." The Act, which also allowed the sale of the donated land to fund a state's land-grant university, specified that military tactics be taught at land-grant colleges and recognized that other branches of science and knowledge should be embraced – effectively extending the land-grant mission to all colleges and departments at Cornell.

Cornell helped organize the first West Africa Conference on the System of Rice Intensification (SRI), which was held in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, in July 2012. Pictured are workshop leaders Gaossou Traore, coordinator of the National Center of Specialization of Rice in Mali, and Erika Styger, director of programs of the SRI International Network and Resources Center at Cornell. See larger image

From their very founding, the land-grant institutions served the public good, then, by educating citizens in practical subjects and by creating new knowledge in fields that were important to their state's economies.

Skorton attributes one of Cornell's most enduring qualities to its land-grant mission: "the commitment to developing knowledge that benefits communities."

This commitment to fulfilling the land-grant mission through public engagement is a distinctive feature of a Cornell education and one that is emphasized in the university's strategic plan. It "depends on the interest and enthusiasm of faculty, staff and especially students to be successful," Skorton says. It is they who "help connect outreach and public engagement so effectively to teaching, learning and research."

Students participate in the Cornell Public Service Center's annual Into the Streets volunteer event to aid communities in Ithaca and the surrounding area. Photo: Kai Keane. See larger image

Ronald Seeber, senior vice provost and a professor in the ILR School, says that public engagement is "in the very culture of Cornell's faculty, even among professors who might not have any public engagement duties built into their job descriptions – from the biology professors who are helping New York state high school classes conduct experiments using supplies and equipment that teachers don't ordinarily have access to, to the English professor who goes out and volunteers in the local prisons; this is just part of Cornell's identity."

Here are just a few stories that show Cornell's spirit of public engagement at work today – in places as familiar as a 4-H after-school program in New York and as surprising as an online repository of U.S. law.

Academic rigor and good citizenship

Wendy Wolford See larger image

The historic collaboration between Cornell and CARE, established through gifts from David '60 and Pat Atkinson, will ensure "that the research will be scientifically sound and locally applicable," says professor Wendy Wolford, associate director for the field of economic development in Cornell's Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future, which set up and administers the collaboration. For example, she says, "We have a team of CARE and Cornell researchers working together on a project to develop locally available fertilizers for agriculture in Ethiopia. … partnering with CARE will make it significantly easier to scale the project up from Ethiopia to Tanzania or Kenya. CARE has that kind of reach, and that's a pretty phenomenal opportunity."

Rebecca Stoltzfus, professor and director of the Program in International Nutrition in the College of Human Ecology and Cornell's provost's fellow for public engagement, is a prime candidate for participation in Atkinson Center efforts like the CARE collaboration. Her work centers on human nutrition, particularly for impoverished children.

In 2009, Stoltzfus congratulates Honest Massawe, the class representative from a collaborative global health and development course in Tanzania that enrolls both Cornell global health and Tanzanian medical students, as the rest of the class looks on. See larger image

Stoltzfus grew up Mennonite and attended Goshen College, a small Mennonite liberal arts school in Indiana. She majored in chemistry. After graduation she went to work for a biotech startup company, helping develop diagnostic tools for monitoring blood sugar and insulin levels.

"But it just didn't feel connected enough to the things I value in life," she says.

As a junior in college she'd spent what she calls a "transformative" semester in Hinche, Haiti, where she assisted in a research project aimed at improving milk yields in goats. "It was eye-opening," says Stoltzfus – not because of the goat breeding experiment (which bred the scrappy Haitian goats with larger, imported Alpine goats), but because of fundamental truths she witnessed as a guest in a Haitian family's home: "the lived realities and experiencing diversity and difference and the incredible joy and hospitality amongst people who were living in very difficult circumstances."

Yearning to get back to that kind of experience, she left the biotech firm and returned to school for a degree in human nutrition. "It was one of the great ideas of my life, really," she says. She graduated from Cornell with a master's degree in 1988 and a Ph.D. in 1992.

CARE International began working with the Cornell Ecoagriculture Working Group to conduct a Global Agricultural Review in 2010. Above, the Guatemala Highland Value Chain Development Alliance, an example of CARE's ongoing agricultural and natural resources strategy with women, provides technical support and market access to farmers to alleviate rural poverty. Photo provided by CARE. See larger image

In her role as provost's fellow, Stoltzfus is at the center of discussions about what part public engagement does and should play in the university's work.

For Stoltzfus, public engagement connects to Cornell's land-grant mission in four ways: finding solutions to problems, asking the right questions in the first place, deepening the educational experience for students and "preparing ourselves and our students to be engaged in democracy, which requires the ability to have conversations with the diverse members of our society and understand where they are coming from.

"This whole notion of public engagement," Stoltzfus contends, "is as much about rigor as it is about charity. It's not just about doing good; it's about being really good at what we do. There are a lot of questions you won't think to ask just sitting at your desk in your office. Part of the knowledge we need can only be obtained by being out in the world."

Cornell students from the Sustainable Neighborhood Nicaragua (SNN) team participate in group activity with San Diego, Nicaragua, residents. See larger image

After spending most of her professional life studying what foods and nutrients young children should be fed, Stoltzfus had an epiphany: "I more and more realized that a big bottleneck was not the lack of knowledge or lack of food, but the lives of women who are the primary feeders and caregivers of children. I could have the perfect food, the perfect message, but if there are not enough hours in her day, if she's being beaten up by her husband, if she's actually clinically depressed, I could talk 'til the cows come home about what food she should feed her baby."

It's a lesson she passes on to her students, not just by telling them, but also by giving them opportunities to engage with communities themselves. "I teach about food insecurity in developing nations, but it's really important for me that my students don't see that as an issue that is out there, outside our walls, outside our neighborhoods," she says, "but [that they] realize that everything we talk about in terms of global problems does exist in our own neighborhood. It's important educationally to realize that and to realize that as citizens."

Staff members from Primitive Pursuits, an educational program of the Cornell Cooperative Extension in Tompkins County, at GrassRoots Festival of Music and Dance in Trumansburg, N.Y., to teach children about nature. See larger image

A 'partnership with the people'

Cornell Cooperative Extension (CCE) has a presence in every county of New York and makes direct contact (through counseling, classes and other programming) with 1.8 million people a year.

Helene Dillard, director of CCE, oversees 1,700 CCE employees around the state. "We work in partnership with the people – it's a multilane, multidirectional educational highway," she says.

From upstate to downstate, including all five boroughs of New York City, CCE deploys agricultural, nutrition, health, family, youth development and urban environment programs. In the Big Apple, for example, CUCE-NYC works with Cornell faculty and the Henry Street Settlement to improve college-readiness of low-income students through an innovative partnership.Other CUCE-NYC programs help high school students farm tilapia fish in their school's basement, develop science curricula around urban agriculture and provide free courses on basic research for adults.

Primitive Pursuits summer program at 4-H. See larger image

A recent example of CCE's responsiveness: Within hours of Hurricane Sandy this fall, it made resources available to victims of the storm. Its New York Extension Disaster Education Network (NY EDEN), eden.cce.cornell.edu, provided farmers, businesses and communities affected by the hurricane with education on hazardous materials, food safety, diseases and best-practice guides on dealing with long-term power outages and agricultural strategies for recovery for growers. NY EDEN also placed extension educators on disaster management and recovery teams.

Kids teaching kids

Citizen U Teen Leader Mariah Crandell with Sue Siebol-Simpson, from the Binghamton University School of Nursing, at a Cornell Cooperative Extension Super Science Fun Camp. Photo: June Mead. See larger image

Like Stoltzfus, Wendy Wolfe, a research associate in the College of Human Ecology's Division of Nutritional Sciences, devotes her work to helping people – in particular, U.S. children – to eat healthier foods.

In October, Wolfe won the statewide 4-H Award for Merit for creating two programs: Cornell 4-H Choose Health Action Teens (CHAT) and Choose Health: Food, Fun and Fitness (CHFFF).

The research that informs CHAT shows that teens learn by teaching, and that when teens become spokespeople for good nutrition, they practice what they preach. An additional benefit is that younger children, who are usually taught by adults, seem to love learning from and engaging with teens.

When she began searching for a good nutrition curriculum for her teens to use, however, Wolfe found that nothing fit the bill, and so she created one herself, with the help of a consultant, dozens of CCE nutrition and 4-H associates and teens giving feedback to fine-tune the course.

The end result, CHFFF, is a fun-packed, game-filled set of lesson plans and materials that has taken New York nutrition educators by storm. Favorites include the lesson demonstrating exactly how much sugar is in a bottle of cola, or the lesson showing how much fat is in the average fast-food burger. "Ewww" is the typical response, says Wolfe, "and they often vow never to drink soda again."

Campers and teen leaders in Binghamton, N.Y., at the end of Eat4-Health Day, where teenagers taught schoolchildren about making healthy food choices. Photo: June Mead. See larger image

In May, CHAT and CHFFF were selected by the National 4-H Council for a 10-state project funded by United Healthcare. Soon, children as far away as Mississippi and Arizona will be learning to eat smaller portions and steer clear of sugary drinks, following lessons developed at Cornell.

June Mead, the association issue leader for Children, Youth and Families in the Broome County CCE, has seen how well CHAT and CHFFF work. Participants in her Citizen U program for at-risk teens are using the curriculum in after-school programs in Binghamton. In October, she traveled to Florida to accept an award from the National Association of Extension 4-H Agents' Urban Task Force for Citizen U's efficacy.

A way out, and up

Richard Polenberg See larger image

Twelve men, all wearing green pants and drab shirts, sit at desks arranged in a semicircle. They are inmates at the Auburn Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison less than an hour's drive from Cornell's Ithaca campus. Built in 1816, Auburn is the oldest operational prison in the United States.

The youngest man is in his 20s; the oldest in his early 50s. All hang on the lecturer's every word, their hands busy jotting lecture notes, their eyes alive with interest.

The course is The Supreme Court, the Constitution and Criminal Justice. The teacher is Cornell Professor Emeritus Richard Polenberg.

Shane Kalb '14 earned 40 credits through the CPEP program and then successfully transferred to Cornell this past fall. See larger image

"This is unbelievably exciting, interesting teaching," says Polenberg, who taught at Cornell for 45 years before retiring as the Marie Underhill Noll Professor of History in 2011, of his first semester teaching prisoners.

"These men are quite extraordinary. I don't know what it is they've done, and I'm not really interested … they are very, very well behaved in the classroom and considerate and thoughtful, and they ask really good questions," says Polenberg, whose teaching excellence earned him a Weiss Presidential Fellowship in 2003.

The course is one of 17 offered this semester, for credit, by the Cornell Prison Education Program (CPEP), which has taught 425 incarcerated men since 2001. (No courses are offered to women because there are no women's prisons nearby.) The program is the culmination of work begun in 1995 by English professor Pete Weatherbee, who, without funding, began teaching in the Auburn prison. Since then, 38 other Cornell professors have taught in the program, with another 30 or so participating as guest speakers. Annual funding of $180,000 comes from the Sunshine Lady Foundation founded by Doris Buffett, sister of investor and philanthropist Warren Buffett.

Last June, the program graduated its first class of 15 men, who earned Cayuga Community College associates' degrees. "You have created a learning community within these walls, and your example holds encouragement for others," Seeber told the prisoners at the ceremony.

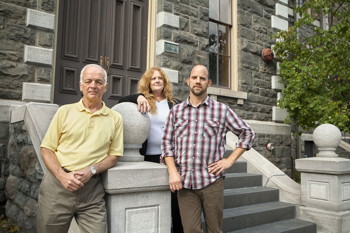

From left, Cornell Prison Education Program faculty director (and plant biology professor) Robert Turgeon, administrative coordinator Marge Wolff and executive director Jim Schechter. See larger image

CPEP executive director Jim Schechter believes that prison education "addresses a problem on which social progressives and social conservatives find common ground: the unnecessary burden on taxpayers caused by the 67 percent recidivism rate among released prisoners. The system isn't working for the public good," he says, "and emerging research shows that education programs like ours reduce that recidivism rate by 20 to 60 percent, so it's a really cost-effective intervention."

Among the new students arriving on Cornell's campus this fall was transfer student Shane Kalb '14, who earned 40 credits through CPEP while incarcerated at Auburn. In August, with good grades and persuasive recommendations from Cornell professors who had taught him behind bars, Kalb moved from his prison cell to an apartment in Collegetown. On his first day, he stood on the Arts Quad in awe. "I have to tell you," Kalb says, "this is the most beautiful place I have ever seen in my life."

Making the connection

Professor Rebecca Stoltzfus chats with students about public engagement. See larger image

Stoltzfus' position as the provost's fellow for public engagement is part of the university's renewed engagement initiative: She works with and is a faculty fellow at Engaged Learning and Research, a universitywide center created in 2011 to strengthen the university's public engagement and public service mission. The center is being funded for its first three years through a gift from the Einhorn Family Charitable Trust (David Einhorn '91 and Cheryl Strauss Einhorn '91) and receives support from the Office of the Provost and the Division of Student and Academic Services.

The center serves as the core academic unit connecting public engagement with Cornell's educational mission, a mission that encompasses the work of plant breeders developing sweeter corn, juicier apples and hardier Brussels sprouts to improve the competitiveness of New York farmers; groundbreaking research in medicine, engineering, business, sustainability and law that saves lives, influences policy and spurs innovation; and the work of artists and designers, poets and philosophers – all of whom also contribute to the education of tomorrow's thought leaders, Cornell students.

"In the broadest sense," says CALS Dean Kathryn Boor, a professor of food science, "our land-grant mission provides key guiding principles that shape the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. From the classroom to the community, the creation and dissemination of 'knowledge with a public purpose' is a driving passion. Building on the land-grant legacy of applying research, teaching and extension to real-life challenges, we are addressing critical needs … across our full spectrum, from fundamental life science discovery to developing effective and sustainable strategies for feeding a population projected to reach 9 billion by 2050."

Access to the law and more

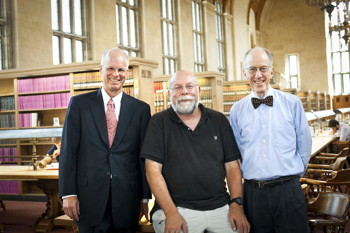

From left, Law School Dean Stewart Schwab, Legal Information Institute Director Thomas R. Bruce and emeritus professor of law and former Law School dean Peter Martin. Bruce and Martin co-founded the LII in 1992. See larger image

The broader definition of engagement encompasses many other parts of the university – even programs and efforts that were not launched or developed with the land-grant mission in mind.

More than half of all traffic to Cornell's Web domain is from people visiting pages of Cornell's Legal Information Institute (law.cornell.edu). Co-founded in 1992 by former Law School Dean Peter W. Martin, now the Jane M.G. Foster Professor of Law Emeritus, and Thomas R. Bruce, then the law school's director of educational technologies, the institute "believes everyone should be able to read and understand the laws that govern them, without cost."

"We were kind of just hot rodding," laughs Bruce, LII director, recalling early forays into putting legal code onto the Web as hypertext. "Let's put it up and see if anybody looks," he remembers thinking.

By 2000, The New York Times was calling the institute "probably the most expansive legal reference tool online." Today it is without a doubt the most comprehensive collection of U.S. law and court decisions available without charge to anybody with access to the Internet. Between 110,000 and 140,000 people visit the site daily.

Ten percent of the site's content is original, mostly written by Cornell Law School students. A regular column analyzing Supreme Court cases is published in the Federal Bar Association journal and emailed to 20,000 subscribers and members of Congress.

The site's impact is widespread. One day, when he was in Japan for a conference, Bruce was introduced to a Vietnamese woman who, upon learning his name, "started acting like I was a rock star," recalls Bruce, who was mystified at first. "It turned out she worked for the ministry in Vietnam that had rewritten that country's commercial code. They'd used us as a primary source on American law."

Another example of engagement through digital access is Mann Library's The Essential Electronic Agricultural Library (TEEAL), which gives faculty, students and scientists in many parts of the developing world offline access (delivered via hard drives) to more than 240 full-text agricultural research and other scientific journals. Before TEEAL, which was founded in the early 1990s, their access had been spotty, outdated or nonexistent because so many of these areas have poor telecommunications infrastructure and limited financial resources.

The nonprofit, digital library continues to expand, thanks to heightened promotional efforts and funding opportunities; recently, new institutions in countries such as Vanuatu and Guatemala have also gained access. TEEAL reaches more than 370 subscribers in 86 countries.

An expanding proposition

In 2005, the Cornell Board of Trustees Committee on Land Grant and Statutory College Affairs, which was formed in 1980, issued its final report and recommended that Cornell become re-involved as a whole in its land-grant mission.

The report explained that while historically, external funding sources had influenced the focus of land-grant programming in the four statutory colleges, "… the land grant designation and mission belongs to all of Cornell." The report recommended further development of the service learning, applied research and outreach potential of Cornell as a whole.

In the years since that report, that broader and deeper engagement has continued – for example, through the creation of the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future, the most comprehensive institution of its kind in American academia; the Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research; and the Engaged Learning and Research center.

"Being a land-grant university, in particular one as prominent as us – only one of two private land-grant institutions in the country and the only land-grant institution in the Ivy League – is a tremendous competitive advantage for Cornell," Harrison says. "We are able to, number one, address the world's problems in a way that many other universities are not, [and] number two, we're able to attract students who understand that; they appreciate that by coming to a place like Cornell they are able to address, meaningfully and immediately, the great challenges that the world faces."

For Cornell to remain successfully engaged, it needs to stay relevant to the prevailing forces of the day, Stoltzfus says, through "technology, increased diversity and globalization, and by responding to a new student generation and the public demand for relevance and career readiness.

"So that's our creative job," she says: "To keep being the land-grant university of the moment."