NEW YORK CITY

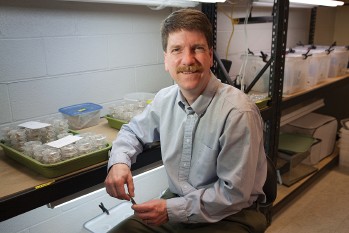

Professor John Losey, pictured on campus, recently asked an audience at the American Museum of Natural History in New York to search for ladybugs, especially nine-spotted ones, and to send him photographs of them. See larger image

New York's state insect is all but lost, but interlopers abound in Big Apple

Cornell entomologist John Losey is a man on a mission. His goal is to discover why the nine-spotted ladybug, New York's official state insect, has all but disappeared.

Jake Segal, age 4, is also looking for answers. He has been finding ladybugs around his 22nd floor New York City apartment since last winter. "I found them in the tissue box," says Segal. "They kept growing."

"It was a mystery," says Jenna Segal, Jake's mom. "We thought we brought a nest home from the beach last summer." So when she read that Losey was presenting a public lecture about ladybugs in the American Museum of Natural History's Linder Theater in April, she decided the Segals needed to be there.

The nine-spotted lady beetle, noted for its white-fringed neck shields and four spots on each wing with a split spot in the middle of the wings, was one of the most common lady beetles through the 1970s, occupying a wide range of habitats. See larger image

Losey told the crowd, which included about 50 children, that with $2 million from the National Science Foundation, he launched the Lost Ladybug Project in 2008 "to help scientists better understand why some species of ladybugs have become extremely rare while others have greatly increased both their numbers and range." The project invites the public, and particularly children, to search for nine-spotted and other ladybugs (there are more than 450 species, each with its own color and spot combinations) and send photos of them to Cornell for identification and inclusion in a database.

"Ladybugs are actually beetles," said Losey. "A predator by nature, ladybugs are more voracious than sharks, bears or wolves." The young crowd gasped. And that's what makes ladybugs so important, Losey said: "We could not grow enough food without ladybugs that eat the pests on [crops]."

A mass of ladybugs on a tree. See larger image

Several decades ago they were so abundant that New York made it the official insect in 1989 after a fifth-grader had lobbied the state to do so. Ironically, shortly thereafter, the nine-spotted all but disappeared, said Losey.

Why? Losey provided several theories. Primary among them is that the introduction of foreign ladybug species by the U.S. Department of Agriculture caused the decline: "As the numbers of foreign species began to rise, the numbers of native species began to fall," Losey said. Also, "because of the possible interbreeding of seven-spotted with nine-spotted, their offspring may not resemble the parents, perhaps having only seven spots," he added. Additionally, a fungus brought in by foreign ladybugs is killing many of the nine-spotted.

A ladybug eats an aphid. See larger image

Today, the two foreign species most commonly seen are the seven-spotted and multicolored Asian ladybug, Losey said. And this is where Jake's mystery meets Losey's project: The multicolored Asian ladybug hibernates on smooth rock cliff faces that are common in their native lands. In our strange land, however, they have adapted by lodging themselves instead on the smooth walls found in apartment buildings. With that news, it seemed as if Losey had solved the Segals' ladybug mystery.

More than 30 nine-spotted ladybugs have been found by young citizen scientists since the Lost Ladybug Project began, Losey reported. Each find has been recorded on the project's website, www.lostladybug.org. Most of them have been found in the western U.S. in very high and dry land densely covered with scrub. Losey has also been successful at breeding the nine-spotted in his lab.

Losey emphasizes that there are few species of rare animals that young people can actively investigate. "Certainly not the giant squid, or the ivory-billed woodpecker," he said. The Lost Ladybug Project offers an opportunity for young people to engage their curiosity and be actively involved with finding and identifying a rare species of insect.

John Mikytuck '90 is a freelance writer in New York City.