COVER STORY

Cornell professor: investigator, comedian, genius, friend

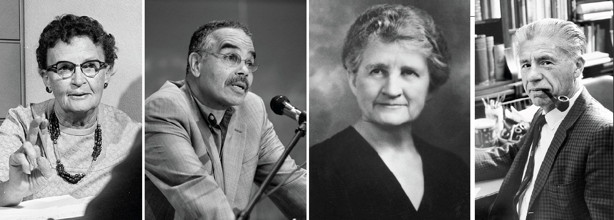

Cornell professors past and present, from left: labor activist and ILR professor Alice Cook, literature professor Kenneth McClane, nutrition professor and home economics college co-founder Flora Rose and literary critic and professor emeritus of English M.H. "Mike" Abrams.

What we're trying to do when we hire a junior faculty member," says John Siliciano, the senior vice provost in charge of the tenure process at Cornell, "is to hire a future legend, someone we will look back at in 30 or 40 years and say, 'That is a legendary professor.'"

Kathryn Boor, the Ronald P. Lynch Dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, offers a description of what Cornell looks for in a prospective professor: "We expect our faculty to shape minds, to ignite interest and to influence each successive generation to want to do more, to do better, and to climb that next mountain to see what's on the other side. We hire new faculty who have that inherent spark – who have the ability to use their own imagination in a manner that captures the imaginations of others."

Kathryn Boor, the Ronald P. Lynch Dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, says: "Teaching is very highly valued in CALS." She proudly points out that in The Princeton Review's recently published book, "The Best 300 Professors," three of the superstar professors selected (from more than 1.5 million professors nationwide) teach at CALS: George Hudler, Karl Niklas and Cindy Van Es. See larger image

Walter LaFeber, Andrew H. and James S. Tisch Distinguished University Professor Emeritus. "You always think of how your lecture relates to this thesis – a tent of knowledge that you're working under – throughout the lecture and throughout the semester," he says. See larger image

Acknowledged faculty legends include people like Carl Sagan, Alice Cook and Liberty Hyde Bailey, who rose to national prominence in their fields while shaping their Cornell departments and inspiring their students. Or long-time or emeriti faculty leaders like Walter LaFeber, M.H. Abrams, Alison Lurie and Roald Hoffmann.

"Great teachers have changed our lives," says Cornell trustee Andrew Tisch '71, who, along with his wife, Ann, gave $35 million to create the Tisch University Professorships, designed to attract and retain the most promising faculty. Andrew and his brother James '75 also created the Tisch Distinguished University Professorship to recognize and support the teaching of Cornell's most prominent faculty members as they near the end of their careers.

"Life-changing" is a recurring theme in testimonials about favorite Cornell professors. For instance, from the ILR School's Memory Book Series: "Professor Neufeld was, without a doubt, the best and most influential mentor I ever had. From him I learnt not only how to think and analyze critically, but also humility and the beginning of the understanding of justice. He was a true teacher," wrote Alfredo Daniels '63 of Maurice Neufeld, one of the college's founding professors.

Or, from one of this year's graduating seniors, Ju Khuan '12: "With the AguaClara program, Dr. Monroe Weber-Shirk has demonstrated how engineers can make the world a better place. His passion and drive to create sustainable water treatment technologies that empower poor communities have been absolutely inspirational. Before starting every semester of research, he first humanized our team's engineering challenges by telling us stories about the people we were helping. He taught us to be excited about those challenges, to have fun with the science, and to really love our work."

Barbara Baird, the Horace White Professor and chair of the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, left, with students. The balance between teaching and research is "part of the joy of being a scientist," she says. See larger image

For tomorrow's legends, along with the many wonderful professors who may never be called legends but who nonetheless make significant contributions to their fields and to education, this is the job: to influence and improve lives. Here are some of the ways this is being achieved every day, in classrooms, labs and libraries around campus.

Investigator

"There is this common notion," says Siliciano, "that there is a difficult and problematic trade-off between teaching and research." But he couldn't disagree more. "Some of the best teachers are also the best researchers. The two skills are not in tension, but feed back and forth."

"That's part of the joy of being a scientist," agrees Barbara Baird, the Horace White Professor and chair of the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology in the College of Arts and Sciences. "Not only pursuing your specialty, but also continuing to think about the basics of your discipline and how that is the foundation of everything we do." She adds: "As we push forward in the cutting edge of research, it's enjoyable to continue to go back to the well, if you will, and think about how our latest experimental results fit together with the fundamentals."

CALS professor of neurobiology and behavior Robert Raguso collects scents with a student in the Mundy Wildflower Garden.

Robert Raguso, a professor in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior and winner of last year's College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Young Faculty Teaching Excellence Award, gives an example of the "mutualistic relationship" between classroom teaching and cutting-edge research. Several years ago when he was a junior faculty member at the University of South Carolina, he had to take over the teaching of Introductory Botany for a colleague.

"We were covering the life cycles of primitive plants, and so I was reviewing that chapter in the textbook. I turned the page and there in front of me was the most beautiful plant, a kind of moss, in brilliant, canary yellow. I thought, 'Oh! A moss pretending to be a flower!'" That encounter led Raguso on a global investigative journey and brought him a major grant from the National Geographic Society. "Teaching really empowers your research and requires a mastery of the subject. There's a real synergy," he says.

Cornell's faculty last year conducted research supported by $655 million in external funds ($430 million for the Ithaca campus alone), mostly from federal agencies and New York state.

"We may be most visible to the outside world through our research programs," says Baird. "That's how we're contributing to society and to the science of the future."

Martha Haynes, the Goldwin Smith Professor of Astronomy. Her research on galaxies produced new models of the universe. See larger image

One who exemplifies this contribution is Martha Haynes, the Goldwin Smith Professor of Astronomy, whose research on the formation and evolution of galaxies produced the first three-dimensional views of sections of the universe and who is working with colleagues on plans to build the CCAT Telescope in Chile. But when you listen to her former students, you are just as likely to hear about Haynes' teaching and mentorship. Ann Martin, Ph.D. '11, who first worked with Haynes as an undergraduate on a summer research project, says of Haynes: "She's always there with subtle guidance and suggestions … and as you get older and wiser, you realize that she has a trajectory in mind for you. She sees you as a whole person. It is very much like having a home away from home."

Comedian, actor and orator

When you poll professors, students and alumni about faculty members who could best hold them spellbound with the power of their words, you hear hundreds of names. Among them: Faust Rossi, who teaches evidence in the Law School; George Hudler in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, who teaches the course Magical Mushrooms, Mischievous Molds that attracts 500 students every semester and merited a 1991 article in Rolling Stone magazine; plant evolutionist Karl Niklas; Susan McCouch, the pre-eminent rice breeding expert; and associate professor of communication Jeff Hancock, winner of the SUNY Chancellor's Award for Excellence in Teaching.

George Hudler works with students in his Magical Mushrooms, Mischievous Molds class.

One name that comes up with impressive frequency is Professor Emeritus Walter LaFeber, a Tisch Distinguished University Professor of history and Stephen H. Weiss Presidential Fellow who retired in 2006. LaFeber, admirers say, speaks in clear, cogent and seemingly perfectly composed sentences, whether delivering a prepared lecture or extemporaneous remarks. His conversation is often peppered with quotations and humorous anecdotes, but also is characterized by a long view of history and an uncanny grasp of how events fit together. LaFeber's class History of Foreign Relations was so popular that students lined up to sit on the floor when there were no more available chairs.

Merrill Presidential Scholar Andrew Kinder '12 writes of Vicki Bogan, assistant professor of applied economics and management: "It is Professor Bogan's intense devotion to perfecting her ability to inspire and teach students that will make her one of Cornell's greatest assets for years to come." See larger image

Another Stephen H. Weiss Presidential Fellow, Glenn Altschuler, the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American Studies, who also has served as dean of the School of Continuing Education and Summer Sessions since 1991 and is vice president for university relations, once called LaFeber "the best thing that's happened to Cornell in the last half century."

Today, when asked to explain his lecturing philosophy, LaFeber says: "There's a larger interpretation that's holding your lecture together. You always think of how your lecture relates to this thesis – a tent of knowledge that you're working under – throughout the lecture and throughout the semester. That helps students get away from the idea, as the old cliché goes, that history is just 'one damn thing after another.'"

Helping students see the connective tissue between seemingly disparate phenomena applies to science and engineering courses, too.

"My favorite class was probably ECE 4870, Radar Remote Sensing, by Dave Hysell," says Brian Harding '11, now a doctoral student at the University of Illinois. Harding had never heard of Hysell before signing up for the class that ended up guiding his future academic pursuits. "He does a really great job of bringing together concepts from other classes. … he's extremely knowledgeable, but instead of giving you the dry equations, he's able to put a little motivation behind it and get you thinking about the process of developing ideas."

Hysell believes that deep personal interest in a topic definitely improves teaching. "I'm very glad that I'm a practitioner of the things I'm talking about," he says. "There's a world of difference between that and teaching out of a textbook. Textbooks for his radar class, he admits, "are terrible – but I don't need a book; I can talk about my own work. It makes it more vital for them. I show pictures from our research at Arecibo and in Peru, at Ija Marka, where I am the principal investigator, and they see these big colossal radars and we talk about experiments we've actually done, and it seems less artificial. Students think, 'I've got to assume that this is actually important, because look, they're doing it today.'"

David Feldshuh, professor of acting and directing, leads activities in his fall 2011 class, Acting in Public: Performance in Everyday Life. Feldshuh is the Menschel Distinguished Teaching Fellow for 2011-12 and is developing a workshop for faculty based on the course. See larger image

Cornell's Center for Teaching Excellence, launched in 2008, offers a course-design institute, professional development grants, seminar series, and other resources to help Cornell professors and graduate students improve their teaching (CTE has worked with more than half of all new faculty over the past two years). The center's Menschel Distinguished Teaching Fellow for 2011-12 is David Feldshuh, a physician, playwright, professor in Cornell's Department of Theatre, Film and Dance and longtime artistic director of the Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts. In his role with the teaching excellence center, Feldshuh is at work developing a course to improve teachers' enjoyment of classroom presentation.

The class' subtitle is "Did you have fun teaching today, honey?"

"By fun," says Feldshuh, "I mean confidence and connection with subject and audience, lack of self-consciousness, a willingness to adventure and explore new techniques, and a sense of presence that communicates to students that the information you are sharing is intriguing to you. Teaching becomes more 'fun' when the excitement that brought the teacher to that material in the first place is made visible." By learning techniques for having more enjoyment in teaching, techniques borrowed from stand-up comedy, acting and directing, Feldshuh believes Cornell faculty can be more engaging to students and, thus, teach them more.

Lorraine Maxwell, left, a professor in the College of Human Ecology who has been recognized for excellence in teaching and advising, says: "I believe that part of my responsibility as an educator is to help students see possibilities they previously didn't know existed I believe that I need to be excited about what I am teaching in order to excite those who are learning." See larger image

Curriculum and course designer

Rajit Manohar, winner of a half dozen teaching awards at Cornell, describes how he designs a curriculum or plans a course: "Essentially, I try to figure out what I want them to know at the end of the semester, and then I work backward from there." And, he says, "You have to structure the labs, refrain from teaching unnecessary material, figure out how you're going to grade, how much weight you'll give to labs, exams, etc."

When Manohar, now an associate dean for research and graduate studies and professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, came to Cornell in 1998, he and two other junior colleagues took it upon themselves to "basically redo the entire undergraduate curriculum in computer engineering." Today, the school's computer engineering programs are consistently ranked among the best in the country.

Rajit Manohar, associate dean for research and graduate studies and professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering. "Essentially, I try to figure out what I want them to know at the end of the semester, and then I work backward from there," he says. See larger image

Raguso, who studies plant and animal interactions, has learned to structure his classes in a way that takes a bit of the burden off of his own shoulders and transfers responsibility to the students instead. The idea came to him after a "dreadful" exam study session in his first semester at Cornell. "It was a horrible experience," he remembers. "I felt like a rabbit in a shooting gallery. The students were throwing questions at me, parsing my words, trying to figure out what would be on the test."

That's when he said to himself: "I'm the one burning 300 calories up here. This isn't learning – this is torture."

His new technique: the exam review session as "Jeopardy." "I write five categories up on the board, break the class into teams, give them a dog toy to use as a buzzer, and I ask them questions taken directly from my lectures. If all the students are stumped, we'll stop and review it. It's playing a game, but it's a ruse to identify weaknesses. And it improved the classroom atmosphere and made learning more fun."

Charles Williamson, the Willis H. Carrier Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (top), and Rosemary Avery, professor and chair of policy analysis and management in Cornell's College of Human Ecology, have both been repeatedly honored by Merrill Presidential Scholars at their annual convocation, where the graduating scholars honor their favorite teachers. (click images for larger versions)

Mentor and adviser

Every May since 1988, the Merrill Presidential Scholar Convocation is held in the ballroom of Willard Straight Hall, and the deans of all the colleges, plus Cornell's president, gather to honor approximately 30 of the top graduating seniors and their favorite teachers.

The scholars are asked to invite two important mentors: one from their secondary school and one from Cornell. It's a chance for graduating seniors to say thank you, in a formal and public way, to the teachers who guided, encouraged and inspired them.

In essays printed in the event programs, the students write about their mentors' confidence-building, care and concern. "Beyond his hard work, Sam believed in me, even before I believed in myself," wrote John Dillon '12, at this year's convocation, of assistant professor Samuel Nelson in the ILR School.

When asked why so many students name him as their favorite Cornell teacher, Bruce Land, a senior lecturer in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, says: "I think a lot of it is like raising kids: it's the amount of time you spend with them. You hear people talking about quality time with kids, but quality comes out of quantity. The same is true for teaching. You just have to put in the hours in the lab, to be there when those learning moments occur." See larger image

Merrill scholars have chosen Professor Charles Williamson, or "Skipper," as his graduate students call him, as their recognized mentor 12 times, putting him ahead of other perennial favorites like Rosemary Avery, professor and chair of policy analysis and management in the College of Human Ecology, who was this year honored for the 10th time. Both are Weiss Presidential Fellows – a title that recognizes tenured faculty members who "in addition to a respected scholarly career, has a sustained record of effective, inspiring and distinguished teaching of undergraduate students." In 2006, Williamson was named New York State Professor of the Year. He has all the attributes of a beloved mentor: significant contributions to his field (fluid dynamics), a sunny disposition, absentminded charm and, more important, intense interest in his students and their academic success.

Another mentor honored this year is James Blankenship, a senior lecturer in the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics. "I remember raising my hand," in Blankenship's class, recalls James Wang '12, "to ask why HIV brings its own transfer RNA, to which he responded, 'No one really knows. Maybe you'll be the one to find out someday.'"

Wang was initially startled by that statement, and then later heartened by it. Maybe he really will make groundbreaking, lifesaving scientific discoveries one day, he believes. Already, Wang's undergraduate research on breast cancer has taken him to two national conferences, and he will soon enter medical school.

And the benefits of student-professor relationships go both ways. "I believe that professors have the very best jobs on Earth," says Boor. "What other line of work will allow you to pursue your own passion in the context of a steady stream of brilliant young minds that provide you with the continual challenge to hone your intellectual edge?"