COVER STORY

Caitlin Strandberg '10 at Slope Media on campus this past spring. See full image

Down economy?

For students, view is only up: Tough job market pushes them to follow their passions and take risks

When she started her job search in the fall of her senior year, Caitlin Strandberg '10 knew it wouldn't be easy. A history major from Orlando, Fla., she wasn't sure where she wanted to take her career. "I picked my major very, very late in the game," she says. At Cornell she had focused on classes and activities – particularly Slope Media, a student radio, TV and print organization she helped launch and run. When she did start looking for jobs, she set her sights on management consulting; but she quickly found that companies were hiring far fewer new graduates than they had in previous years.

"I never could have anticipated … how significantly the [economic] downturn had impacted the availability of entry-level jobs," she says. "You hear about it, but you think it can't be that bad – and then you go onto the [Cornell] Career Services website and you see all these companies that came last year and the year before, and it seems like it was slashed in half. Anything I was interested in was just not happening."

Two years after the financial crisis of 2008, and with the recovery from the Great Recession faltering, college graduates across the country are continuing to feel the effects of the 9.6 percent unemployment rate. Entry-level positions are scarce, and competition is fierce. With fewer companies actively recruiting, applicants have less opportunity to meet or talk to potential employers – and it's hard to make a strong impression through an online application. "It's really emotionally exhausting," Strandberg says.

But for Strandberg and many of her classmates, new vistas are opening up, and with them an unanticipated readjustment of expectations. With perseverance, creativity and a willingness to take calculated risks, the students are heading off on paths that are very different from – and, in many cases, much better than – the ones they had imagined for themselves just a few years ago. Some are finding themselves thrust into unexpected professional challenges, some are heading off to graduate school and yet others are finding inspiration in vocations, from Teach For America to the United Nations.

Larry Stevens '10, right, spent the summer training as a Teach For America recruit in a Philadelphia high school (pictured with student Anthony Davis, '17); Stevens is now teaching in Washington, D.C. See larger image

An 'excuse to take a risk'

The economic climate is changing job searching in a positive way, says Rebecca Sparrow, director of Cornell Career Services. The new employment landscape is encouraging some graduates to take interesting side roads and explore areas that are less obvious, but that could ultimately turn out to be even more fulfilling.

"I think we're seeing a shift in the notion that you've got to be launching your ideal career leaving college," Sparrow says. "People are understanding that that's not the case. … In a way, the tough economy has opened students' eyes to reality a little bit earlier" in their lives.

Or as the now-employed Strandberg puts it: "The [economic] downturn kind of gives you an excuse to take a risk. And high risks reap high rewards. So why would you not use the excuse?"

The numbers reflect many of the changes affecting graduates' search for their first long-term jobs. Statistics show shifts that seem small when taken individually, but may be more significant from a big-picture perspective. Based on surveys of graduating seniors, 50 percent of the Class of 2009 (data from the Class of 2010 is still being collected) had found jobs by graduation or up to seven months afterward. That's down from 55.2 percent in 2008 and 56.4 percent in 2007. (Response rates are around 75 percent.) The lower figures in 2009 are partly because more graduates are staying in school for advanced degrees: 34.3 percent of the Class of 2009 went straight to grad school, compared with 32 percent in 2008 and 30.1 percent in 2007. And there is a small rise (15.7 percent, up from 12.8 percent in 2008) in the number of students who fall into the catch-all category "other endeavors," which includes short-term service jobs, volunteer positions, internships and fellowships; so-called "gap year" pursuits (ventures that allow graduates to explore new places or vocations for a year or so before entering either graduate school or a more permanent position, as well as those still looking for work.

"More students are looking at gap year opportunities – things like AmeriCorps or short-term fellowships that will help them build really excellent job skills but are not intended to be a long-term solution to the job puzzle," Sparrow says. "We are seeing a lot more flexibility."

The surveys also show that fewer seniors are relying on on-campus recruiting, which is greatly diminished. Instead, more are using networking and alumni connections. And colleges are reaching out to alumni more than ever. "We've had wonderful responses from alumni," says Mark Savage, director of the Office of Cooperative Education and Career Services in the College of Engineering. "There are jobs out there; they're just not going to be in your face like they were three years ago. You have to turn over some stones."

Stephanie Evans '10 originally planned on a job in management, but then focused on the fashion industry and is now a merchandise assistant at Macy's in New York City, working for macys.com in the men's shoes division. See larger image

And harrowing as the uncertainty can sometimes be, it puts this year's graduates at an advantage in the long run, Sparrow adds. "When they have learned as undergrads about all these things – having a multipronged job search and doing networking – they're better able to manage their careers down the road. These students really are developing skills that will last. That's sort of a bitter lesson to learn, but down the road they'll be in better shape for taking the next steps in their careers."

In Strandberg's case, months of job searching led to some thorough soul searching. So when entrepreneur Scott Belsky '02 spoke about his New York City startup in one of her classes, something clicked.

She stuck around after the lecture and chatted with Belsky. The more she learned about his new company, which offers tools, products and information to help creative professionals organize their work online, the more she realized it was exactly the kind of job she was looking for.

On July 26 of this year, Strandberg joined the company as associate director of business development.

"In some ways, the recession prevented me from jumping into a role that wouldn't have fit my personality or been the best opportunity for me," she says. "This is exactly what I wanted, and in some cases I didn't even know that I wanted it."

She admits she is taking a risk by joining a startup company. But taking risks, job counselors say, can lead to valuable experiences at a time of life when job seekers are unencumbered by family responsibilities.

Following their passions

Stephanie Evans '10 has taken the lesson to heart. An applied economics and management major, she started her job search broadly, applying to various kinds of management training positions. She would have preferred employers to be attracted by her good grades and strong internship experiences, but as a peer adviser at the career center, she also knew that connections, persistence and creativity are what really count in this economy.

So she narrowed her focus to the industry she loves most: fashion. By early May, she was whisper-close to an offer that never came. But she persevered, and by June she was starting her first job as a merchandise assistant at Macy's. "People who are truly passionate about the work they do are the ones that are the most successful in their careers. And I want to be really successful," she says. "This is something I really want to do. I'm going to make something happen; it's just about staying persistent."

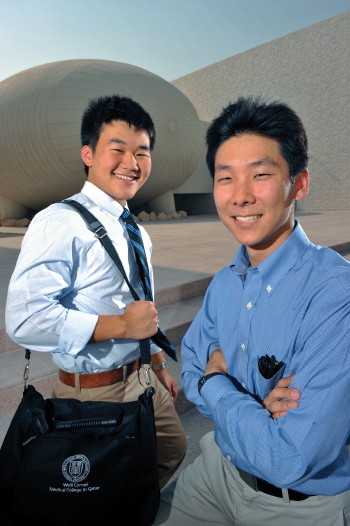

Jack Cao, left, and Jonathan Soh, both Class of 2010, are spending a gap year at Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar as teaching assistants; they chose the jobs for the cultural and teaching experience. See larger image

She notes the irony: Had the economy been better, "there would have been other opportunities in other industries ... and I would not have really looked into the fashion industry. I would not be following my passion."

Often that passion involves community service. Recently Larry Stevens '10 stepped back into the classroom – this time as a high school Spanish teacher in Washington, D.C., through Teach For America, a not-for-profit that trains recent college graduates and places them in teaching positions in underserved public schools.

Cornell is a major source of TFA recruits: Between 10 and 11 percent of graduating seniors apply to the program every year. Teaching wasn't what Stevens always imagined he would be doing after college. With a bachelor's degree in Africana studies, he had a long list of potential employment pursuits, including running his own company.

"But back in '08 when the economy got really bad, I started seeing the headlines. … I thought, teaching is something that I definitely should be doing now," he says.

That view was shaped by his early experience. Before winning a scholarship to a private high school, he attended public school in Jersey City, N.J. – one of the state's most troubled school systems. He remembers classes of 40 to 50 students and "an atmosphere of hopelessness."

"Teachers are there disciplining, not really investing personal time. You feel not loved; you feel unwanted. That sticks with you," he says.

He hopes to help change that mindset for the next generation, first as a teacher and eventually as a principal and administrator. "I want to go to D.C. and have black male students look at me and say, 'You did it; I know I can.'"

Beyond the chance to make a difference, TFA also offered something crucial for a family in which a grandmother and siblings count on Stevens for support. "Everything was definitely gearing me toward staying focused and making sure that I had a job, because I can't afford to not [have a job]," he says.

Helping to improve underperforming schools is appealing even for students who have a financial safety net, says Ian Hillis, director of recruiting for TFA at Cornell. The economy leads students to reflect on others who are not as lucky as themselves, he says, and to look for ways to help.

Ideals about helping fix society have a long tradition at Cornell. Between 25 and 35 Cornell graduates enter the Peace Corps every year, and this year many more students are seeking jobs with the federal government, both domestically and abroad.

Rebecca Vernon, J.D. '10, on campus this spring; she saw the position she landed at a law firm deferred due to the economy and took the extra time to work with law professor Cynthia Farina on designing a website to make federal rulemaking more accessible to the public. See larger image

"Since the financial crisis hit, I've seen a huge upswing in the number of graduate students interested in federal employment opportunities … and in working within the United Nations," says Thomas O'Toole, assistant director for professional development at the Cornell Institute for Public Affairs.

O'Toole attributes this to the decrease in private-sector hiring, to more projected government vacancies, as well as to a renewed optimism among young people about the power of government to effect positive change. "Cornell is well positioned to become an attractive target institution for federal employers," he says, which is only fitting for one of the original land-grant universities.

The Peace Corps isn't the only draw for Cornell students with wanderlust. Jonathan Soh and Jack Cao, both '10, headed overseas after graduation, but without leaving Cornell. The two are teaching assistants at Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar – a gap year job they chose for the cultural and teaching experience.

Cao is a teaching assistant for Psychology 101 – a job he had held as an undergraduate and calls "the defining experience" of his college career.

"The one big regret I have during college is not studying abroad," he says. "I see going to Qatar as a way to fulfill that [goal] – to have that abroad experience while doing something I love."

And the paycheck helps, too, he says. "After my parents spending so much money for an undergraduate education at Cornell, it's hard to ask them to shell out more money for graduate school. I'd like to take on as much of that financial burden on my own as possible."

Soh agrees. "Given the dismal financial landscape, it was especially important that my time off from schooling wouldn't create an additional financial burden for me and my family."

Delayed reaction

For graduating law students, the landscape has changed dramatically just over the last year. Most large law firms have cut their hiring by half or more in the last two years, even as the number of new law graduates is rising. And because law students are usually offered jobs by the summer before their third year based on interviews that start a year earlier, the Class of 2009 was the first to feel the effects of the 2008 crash.

Last spring, the Law School added a staff member to its career office to help. "If you compare the number of law students in the United States generally to the number of jobs that are predictably available from one year to the next, there's a supply and demand problem," says John DeRosa, assistant dean for student and career services. "To say that this market is brutal, and will probably continue to be – if anything, that's an understatement. So we need to do everything we can possibly do to uncover every quality opportunity there is."

And the school is reaching out to alumni more than ever before, he adds. "The bad news is, the market requires us to do that. The good news is, the alumni have been incredibly helpful."

They have also expanded and redesigned an externship course to offer credit to students for summer internships, a step that allows employers not traditionally in a position to offer paid summer positions (such as judges, government agencies, nonprofits and corporations) to increase their use of law student talent during the summer.

"Historically, most of the students in [the externship course] worked for federal judges. This is the first year in which we've really tried to generate a private sector component," DeRosa says. By granting course credit, the program allows firms and companies to take on students as volunteers – a practice otherwise restricted by labor laws.

Overall, he says, the tough market is likely to affect graduates from schools with less prestige much more than those from Cornell.

"I'm biased, but I think the benefit of going to a very good, very highly regarded law school – as difficult as the market is, [it's] going to become more pronounced," he says.

Major cases, major impact

And as with other Cornell students, members of the Law School's Classes of 2009 and 2010 are finding a few golden opportunities in the recession.

Like many of their classmates, Silvia Babikian, J.D. '09, and Rebecca Vernon, J.D. '10, secured positions with law firms in New York well before they graduated only to find their starting dates deferred for six months or more. In the meantime, their firms are paying them a stipend to work for a nonprofit or community service organization.

Babikian started work at the American Civil Liberties Union in Los Angeles last fall, gaining an opportunity to work on major cases that very few first-year associates get.

The first case she worked on, Salazar v. Buono, challenged the constitutionality of a religious symbol on federal land and was recently heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. "I honestly didn't expect that I would get this kind of experience," she says. "I like the sense that I really have an impact on someone's life with the work that I do."

Vernon's interim work also has national significance. Working with law professor Cynthia Farina, she's designing and testing a website to make the federal rulemaking process more transparent and accessible to the public.

Federal rulemaking is "an incredibly participatory part of our federal government's work," Vernon says. "Federal agencies are actually required by the courts to respond to citizens' comments. I'd like to make people more aware of that."

In the spring, the website project, which partners with the U.S. Department of Transportation, used the site to explain a proposed federal ban on texting while driving by commercial truck and bus drivers.

"This isn't where I thought I would end up," she says, "but I'm so happy to be where I am."